A map for every journey

Posted onRemember the world before Google Maps?

When I started driving, the front passenger was the navigator. They plotted the route, then kept their finger on the map and watched the exits until we reached our destination. The success of the journey depended on them. If you found a really good one, you married them.

Trips to new places were still an adventure. We navigated by dead reckoning. We followed pre-printed instructions and paper maps that only showed arteries. We took directions from relatives on the other end, and if the navigator failed, from strangers along the way.

When we got lost, we got lost. There was no blue dot indicating our position, no blue line to guide us. We had to figure out where we went wrong, and find our way back. It was nerve-wracking. It strained relationships. We had screaming matches in Tim Hortons parking lots.

Now, we have Google Maps. We no longer get lost. The navigator queues songs, passes snacks and picks restaurants.

Maps made the journey predictable. We know exactly how to get there, how long it will take, what difficulties we can expect, and where to go if we have a problem.

It made navigation completely stress-free.

So why don’t we have this for other kinds of journeys?

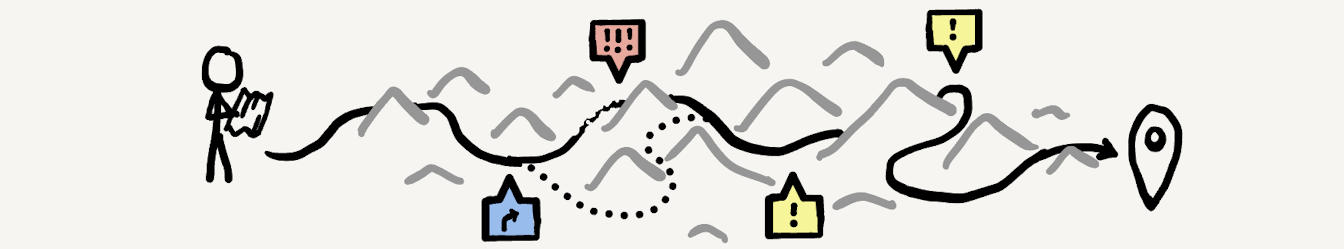

I help people navigate German bureaucracy. The people I help are on a different kind of journey, but their concerns are the same: they want to know how to get there, how long it will take, what difficulties they can expect, and where to go if they have a problem.

The stakes are higher than showing up on time for dinner. Some people are fighting for their right to live in Germany. Their whole family is sitting in the car with them. They put their life savings in the tank.

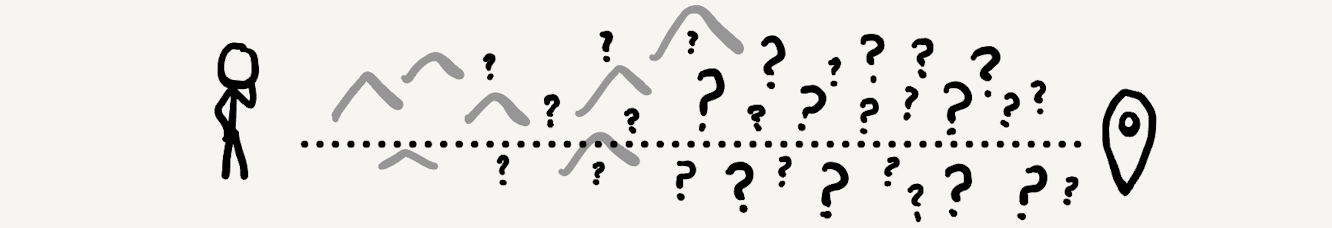

There is no GPS this time. There isn’t even a map. There are only scarce, ambiguous instructions and rumours from fellow travellers.

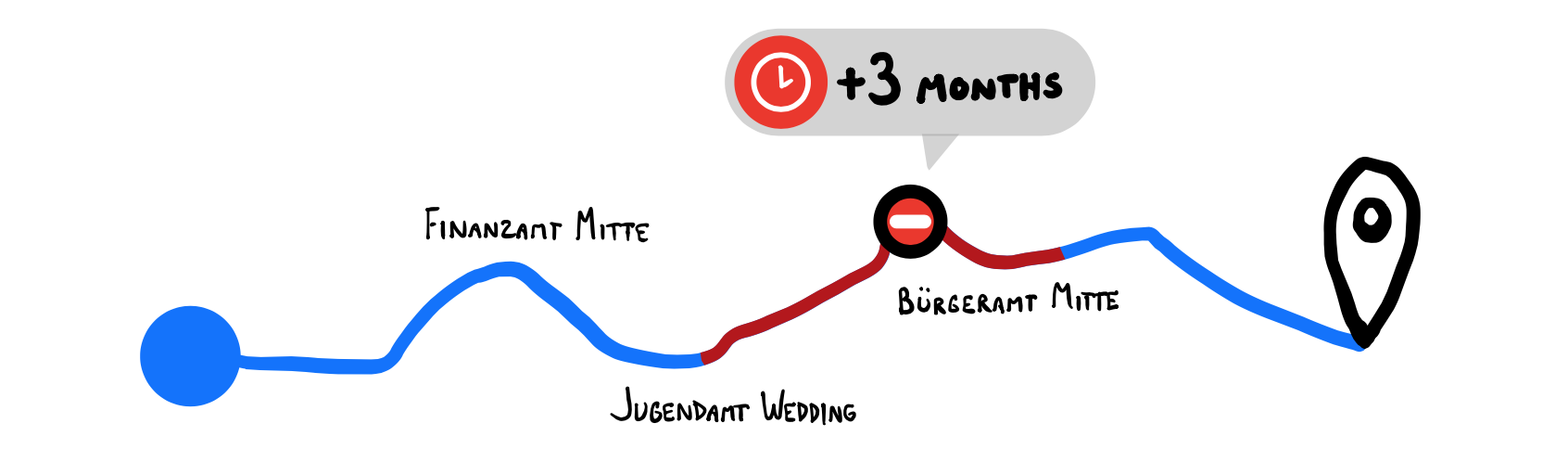

A map would make the journey predictable. It would not fix the months-long bureaucratic traffic jams, nor would it turn business registration into a scenic drive, but it would give people a sense of what’s ahead, and they could prepare for that. Remove the uncertainty, and you remove most of the anxiety.

I don’t picture a literal map, just good information that fills the same role, anything that prepares travellers for their journey. I’d settle for plain text and some flowcharts.

This is hardly a revolutionary idea. How can you watch people take the same wrong turns over and over again, and not want to put up a sign? Ask your civil servants.

So I’ve been drawing maps and putting up signs myself for the last 7 years. I’ve mapped dozens of bureaucratic processes in Berlin, and a few more in other places. I make a living out of it.

But I face the same problems as any cartographer: the world changes faster than I can map it. A lone surveyor can only cover so much ground. It’s hard to keep abreast of all the changes across all of the topics I cover.

Unlike Google, I have limited visibility into what I map. I don’t have satellite imagery of bureaucratic processes, nor camera cars that roam around the Bürgerämter. I don’t even have reliable contacts there. I just read forum posts and ask around. It’s a lot like drawing a map by interviewing travellers.

I want to get much better at it. I automated some of the change monitoring, reduced the scope of the website to mostly Berlin, and built relationship with people on the ground. I set up knowledge-sharing group chats with relocation consultants and immigration lawyers. I have also built a humble social media audience that I poll on occasion.

The next logical step is to get much better data. In my mind, I think it’s possible - albeit challenging - to gather data about bureaucratic processes from the outside.

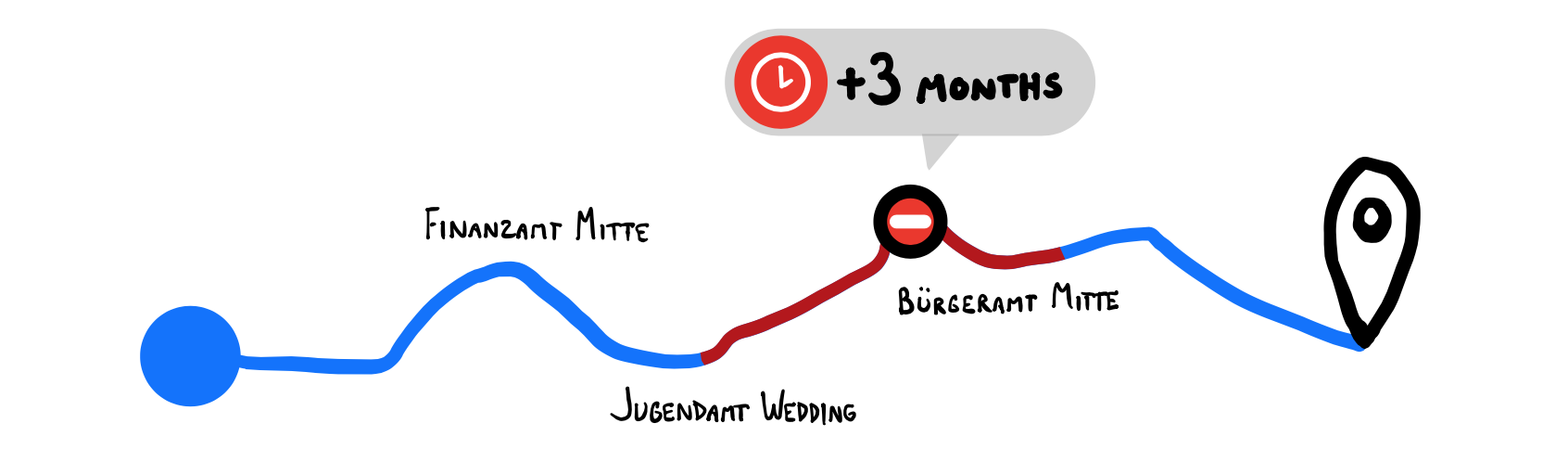

Google has millions of smartphones observing traffic conditions in real time. This is how we know precisely how jammed the A2 is on a given day. I think we can do this for German bureaucracy too. If we collect enough data about people’s bureaucratic experience, we can give people an idea of what journey they’re getting themselves into. Traffic conditions, but for German bureaucracy.

If even a single-digit percentage of my readers let me know how their journey went, this becomes possible:

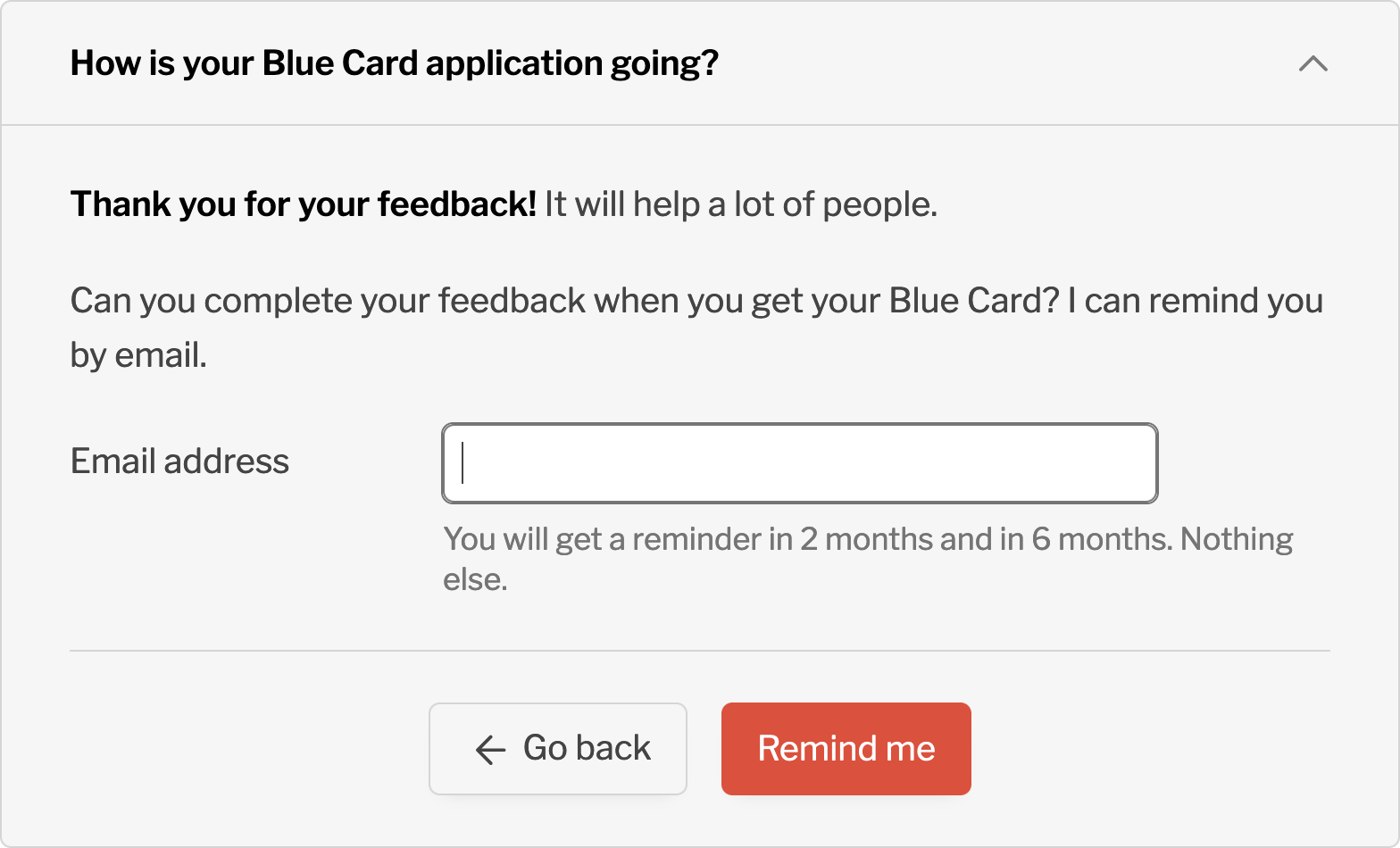

The biggest challenge is timing. My readers come to me at the beginning of their journey, but I need their feedback at the end of it.

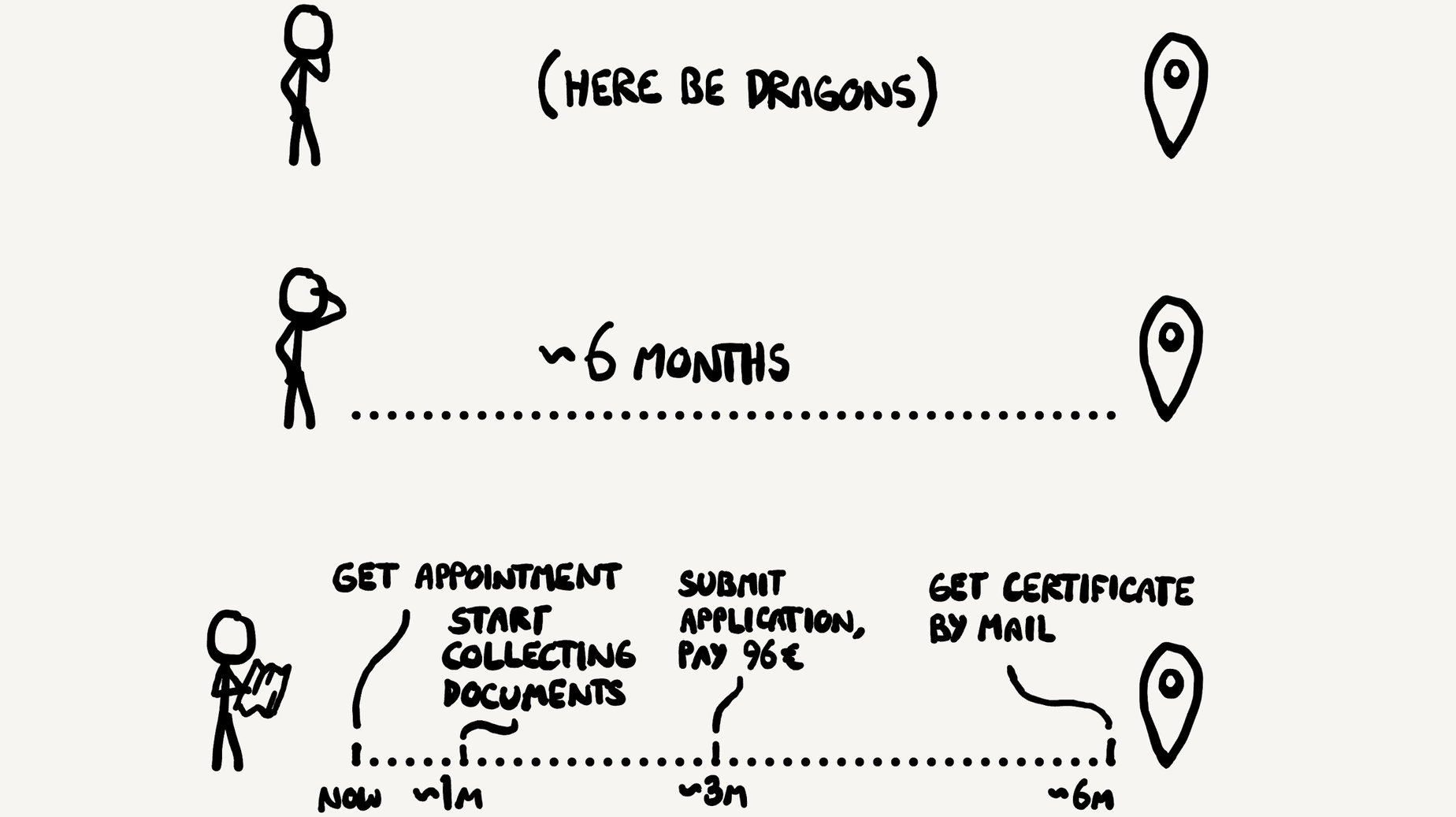

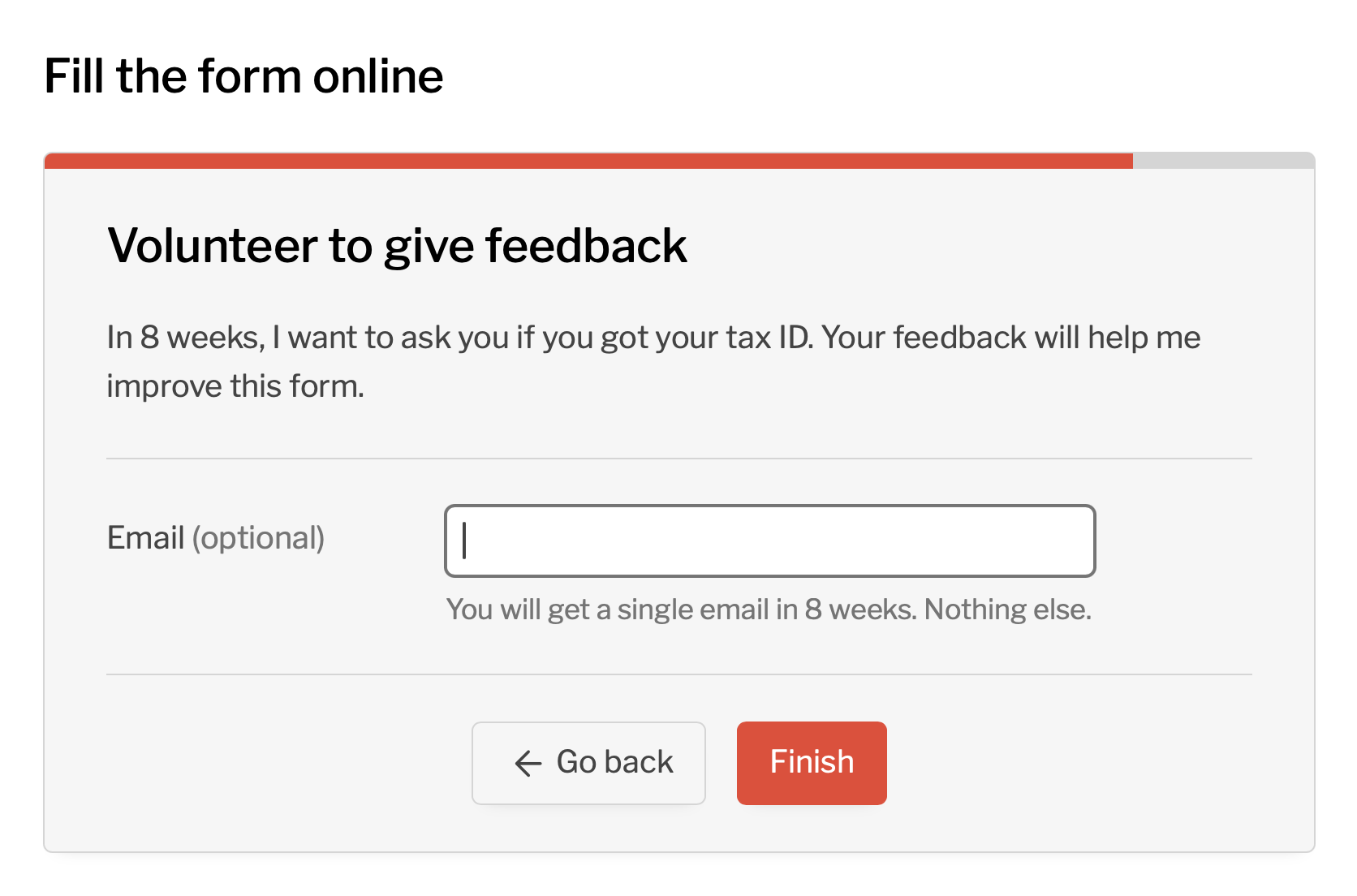

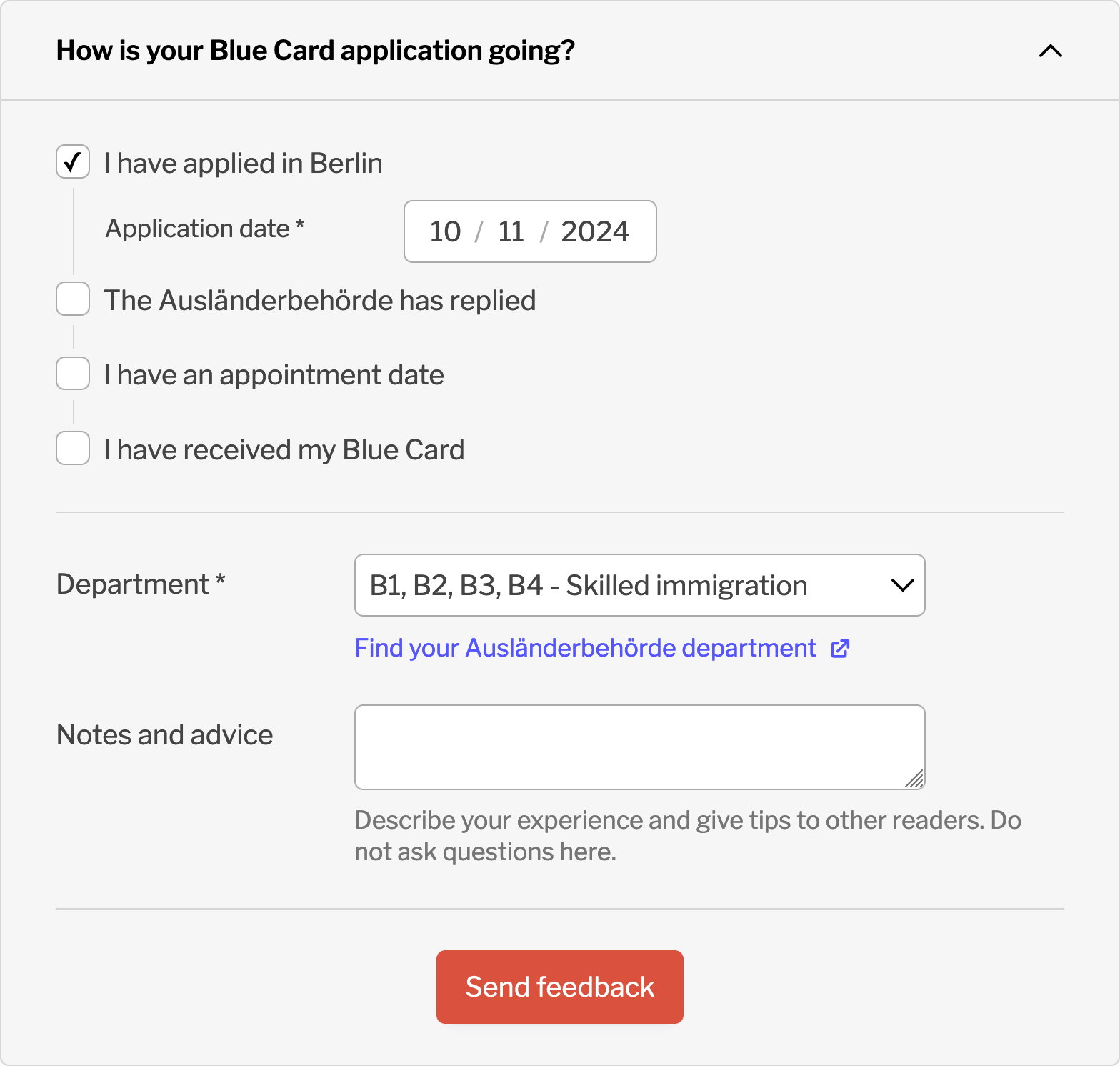

This is what I have come up with:

This is a step in the form to request a new tax ID. If all goes well, a reader should get their tax ID around 6 weeks after using this form. Then, if they volunteered to give feedback, they get an email with a few questions. I ask at precisely the right time.

The form went live two weeks ago, and 40 people already volunteered to give feedback. This is far more than I expected. In a few weeks, responses should start trickling in.

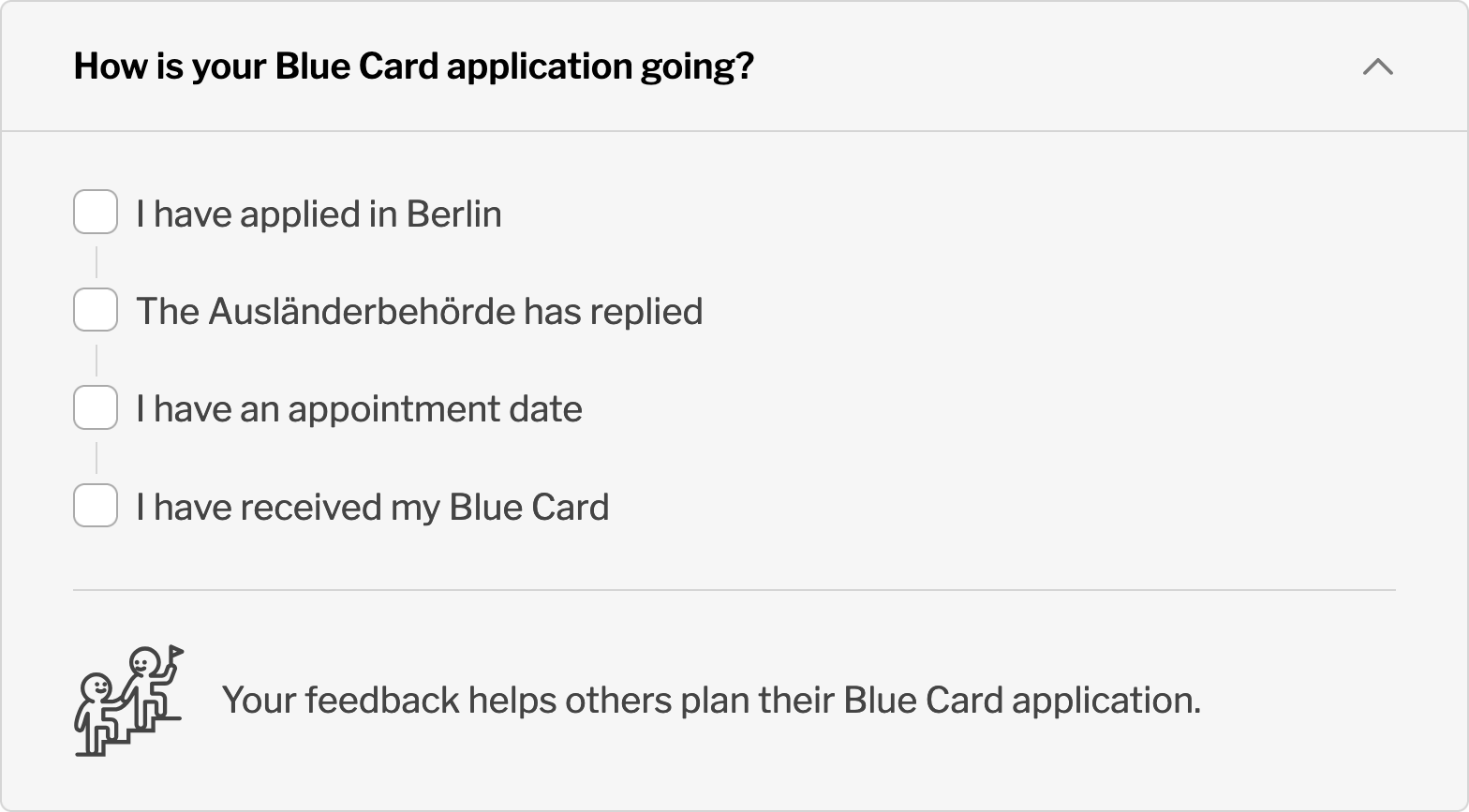

If this works well, I want to replicate the success across the entire website. If I know precisely how long it takes to get a work visa, to register a business or to become a citizen, I can make people’s journey a lot more predictable.

In October 2024, I have built a form to collect feedback about the immigration office processing times. It comes with a nice tool to visualize average wait times by department, and individual reports from readers. Read more about it.

If all goes well, we will get more insight about the immigration office wait times than ever before. For people who have been waiting for over 6 months for a residence permit, this will be a game changer.

Related ideas

- The duty to document

- All About Berlin is the embodiment of this

- Immigration office wait times is a map for the Landesamt für Einwanderung

- Guerilla public service and the guerilla groundsman’s random acts of tidying.