All About Berlin

Built inSince 2017, I run a website called All About Berlin. It hosts a large collection of detailed guides that help immigrants settle in Germany. It helps them navigate the kafkaeske bureaucracy and figure out all the little systems that make up German society. It’s my full time job since 2020.

Put simply, it shows immigrants how to adult in Germany their new country.

A rather famous website

All About Berlin is quite famous among immigrants. Pick a random one from the crowd, and there is a pretty good chance that they have used All About Berlin at some point.

It’s often praised for giving clear, straightforward and practical advice. More and more, it also gets praise from native Germans who get better answers from my guides than from official resources.

Why I built it

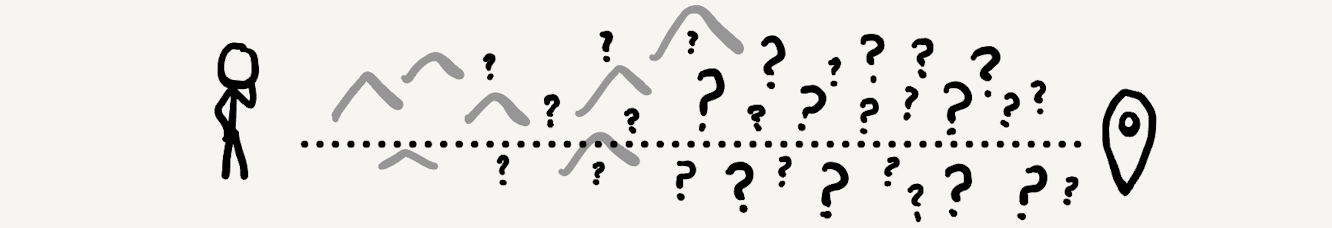

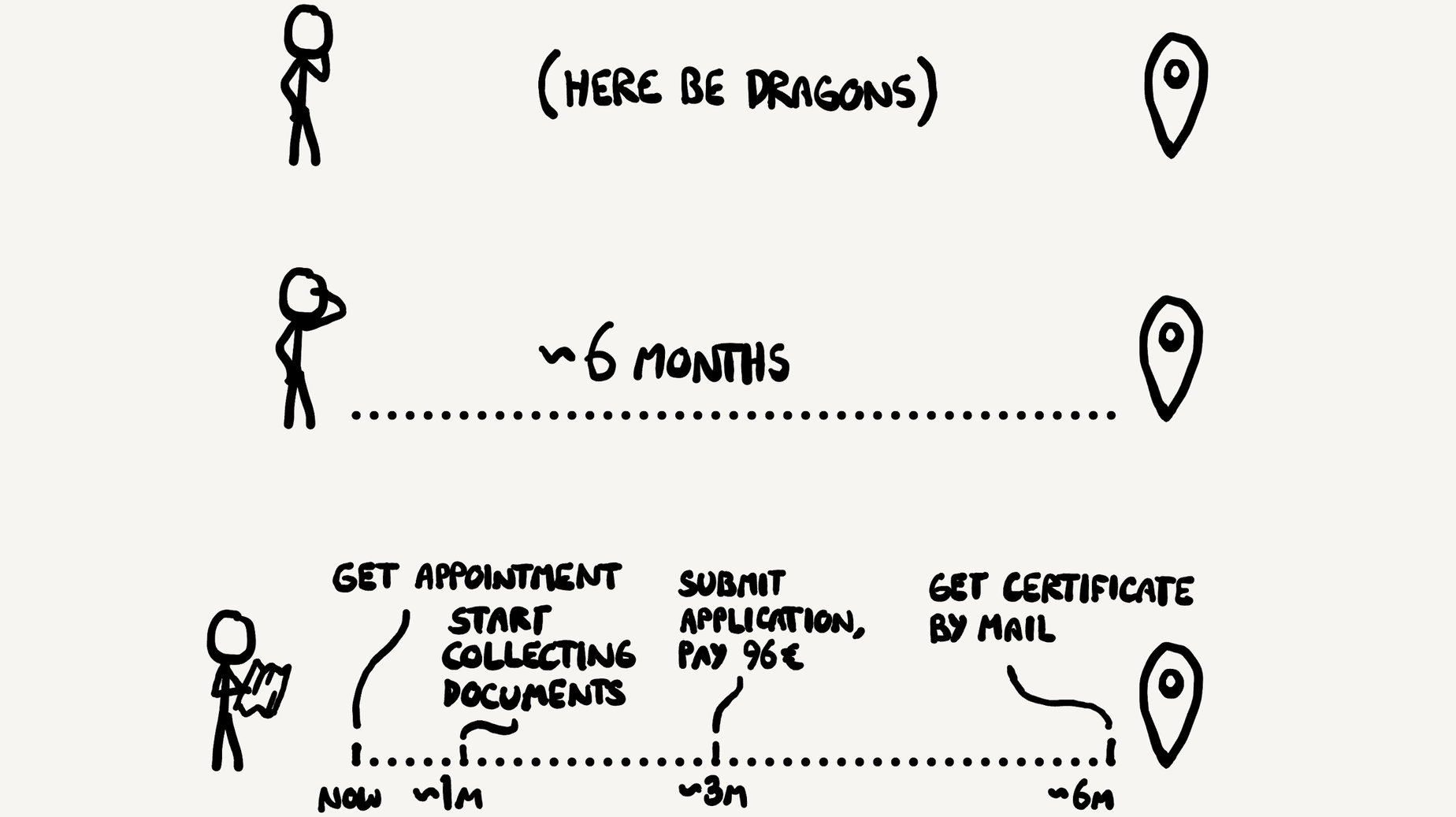

Uncertainty causes anxiety. Everything is more stressful when you don’t know where you are, where you’re supposed to be, where you’re going or how long it will take to get there.

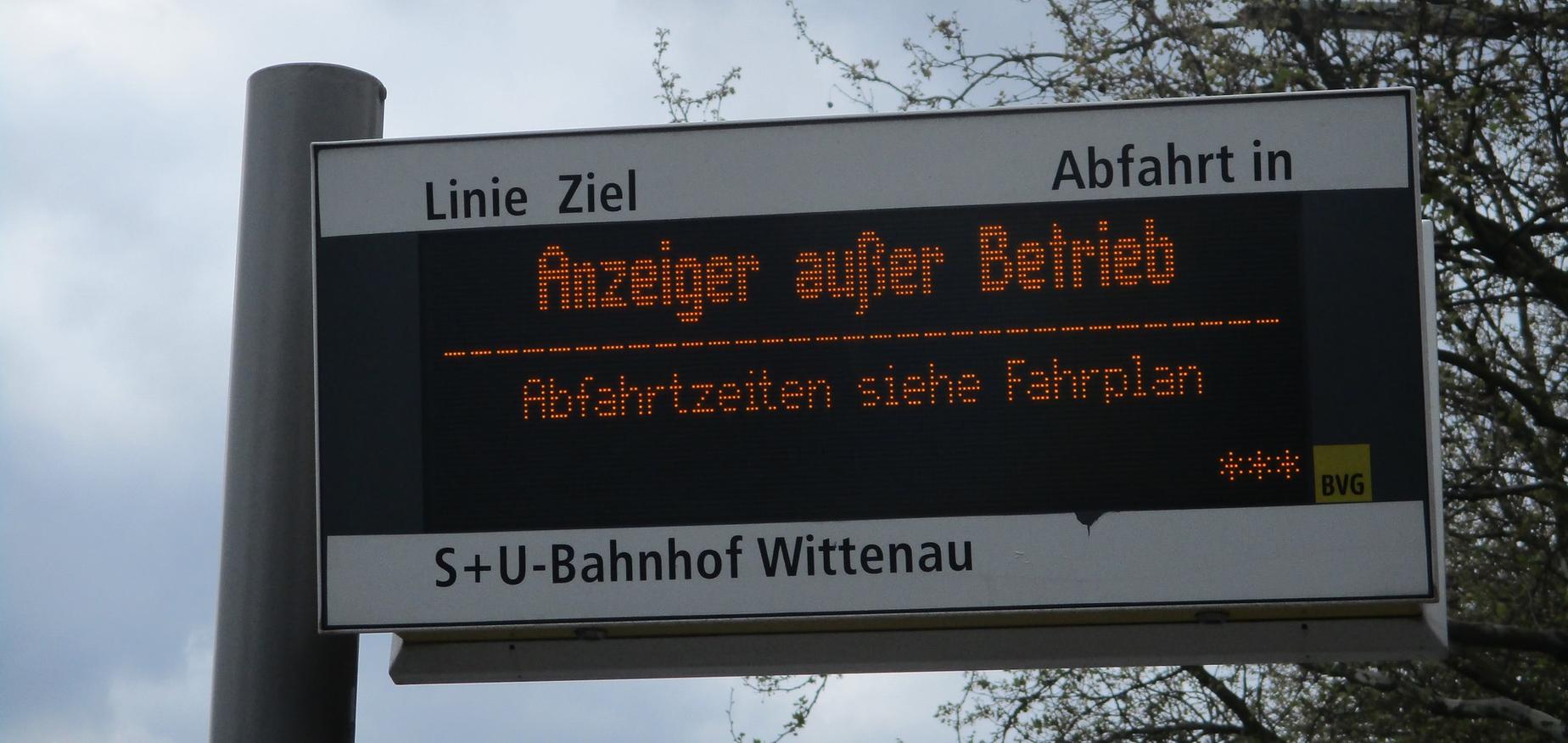

What bothers us about waiting for a train, a taxi or a piece of paper is not so much the wait itself, but the degree of uncertainty. Waiting 10 minutes for a train is fine, so long as you know that it’s coming in 15 minutes. Even delays are palatable, so long as you are informed of them.

But if you don’t know when the train is coming, or whether it’s coming at all, you will start stressing long before the 10 minute mark. At what point do you give up and call an Uber, or tell your boss that you will be late? One missing piece of information adds a lot of anxiety to the journey.

This is something Uber has done brilliantly. You no longer need to stand outside, wondering when your cab is coming or whether the driver got the address right. Your phone shows you where they are, and buzzes just as they turn the corner. The experience of waiting is greatly improved by knowing how long you’re going to wait.

That also applies to bureaucracy. When you reduce uncertainty around a bureaucratic process, you improve the entire experience. This is the guiding idea behind All About Berlin. Add clarity, remove anxiety.

The cost of uncertainty

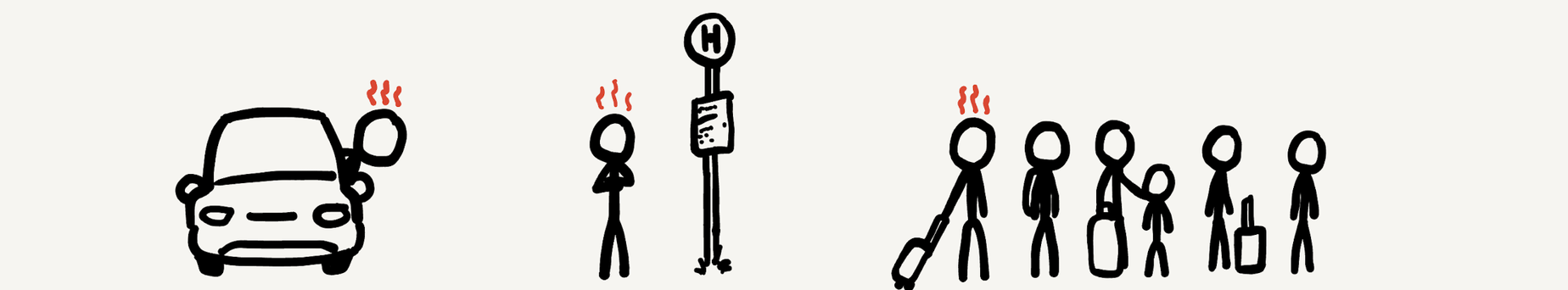

Uncertainty has a cost. You leave home earlier because you don’t know how long it will take to find parking. You take an early bus because public transit is unreliable. You get to the airport early because you don’t know how long the security check will take. You waste time and energy to account for the unexpected.

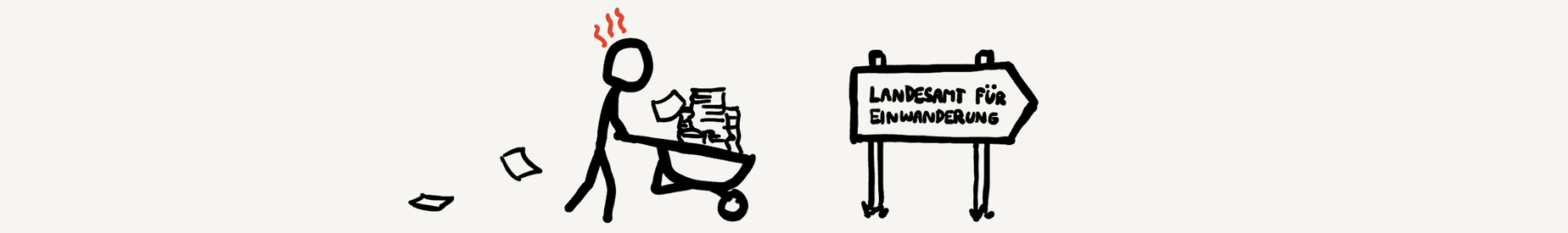

Likewise, we tell people to bring every document they can to their immigration office appointment. A missing document can delay their residence permit application by weeks. They risk burning through more of their savings while they wait for the permission to work. It can cost them their job, and even their life in Germany.

The stakes are too high and the case workers too capricious to bring just what’s officially required. Therefore, people chase documents they don’t need and get them translated at great expense, just in case a capricious case worker might ask for them.

This sort of uncertainty wastes everyone’s time and energy. Not only immigrants who waste time chasing unnecessary documents and energy stressing about the outcome, but also case workers who waste their labour processing incomplete applications.

Engineering school drilled into us that the earlier you catch a mistake, the cheaper it is to fix. Good instructions are the earliest, cheapest fix their is. Well informed people prepare better, and you waste less time dealing with them. It saves everyone a lot of unnecessary work and frees up resources for better uses.

Uncertainty leads to avoidance

In the worst case scenario, uncertainty leads to avoidance.

When I travel, I often struggle with local public transit systems. There’s just so much to figure out! Do I need a transit pass? Do I need an app? Can I just pay with my credit card? How much does it cost? How do tariff zones work? Which bus am I supposed to take? In which direction? When is it coming? Do I need to tell the driver to stop? Can I exit through the front door? Do I have to tap my card on the way out?

Sometimes it’s too much trouble, so I just walk.

Speaking of foreign systems, in Taiwan, I really struggled with ordering food.

To order food, you need to:

- Find the paper slip you use to choose which items to order. Sometimes they bring it to you, and sometimes you just wait at your table, clueless, until you realise there’s a pile of them in a box somewhere.

- Understand the Chinese menu, filled with Chinese dishes with unknown portion sizes.

- Decide what you want and how much of it you can eat.

- Figure out how to transmit that paper slip to people with whom you have no common language.

- Hope to God that you did everything right, and that you will eat today.

This was at the end of a long trip, and I was completely worn out. I did not have the energy to do this, so I did what every weary traveller would do in my situation.

I went to McDonalds.

Everything was exactly like at every McDonalds everywhere else. I used the multilingual self-service kiosks, paid with my card, and picked up my mediocre but predictable meal the same way I would anywhere else in the world.

This sort of avoidance also happens with bureaucracy. People develop what I call envelope anxiety. They get a scary letter from the Finanzamt. They don’t understand German taxes. They don’t even understand German. They have no one to turn to who can make sense of it.

So they ignore it. The envelope stays unopened on the kitchen table, and naturally, whatever problem they are ignoring only gets worse.

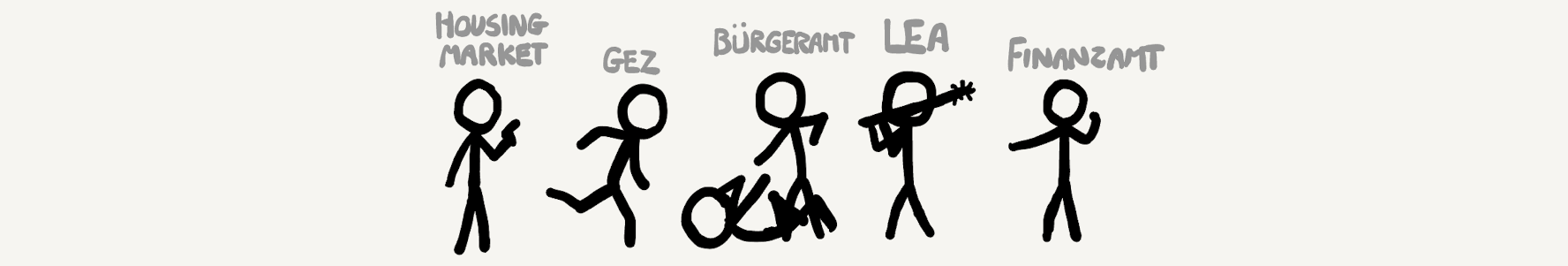

This affects immigrants more than anyone else, because they face the whole system at once, instead of being gradually exposed to it as they grow up.

In their first few months, they need to find a job and an apartment, open a bank account, choose health insurance, get a SIM card, get an internet contract, find a kindergarten for their children, and a million other things.

They also need to figure out all the small systems: recycling, tipping, taxes, Sunday shopping, public transit, taking sick days and so on. Even little things like finding the eggs at the supermarket (hint: not in the fridges) adds friction to their day-to-day life.

They must do all of that while going to work, taking care of children, paying bills and running errands like the rest of us.

It can be a lot.

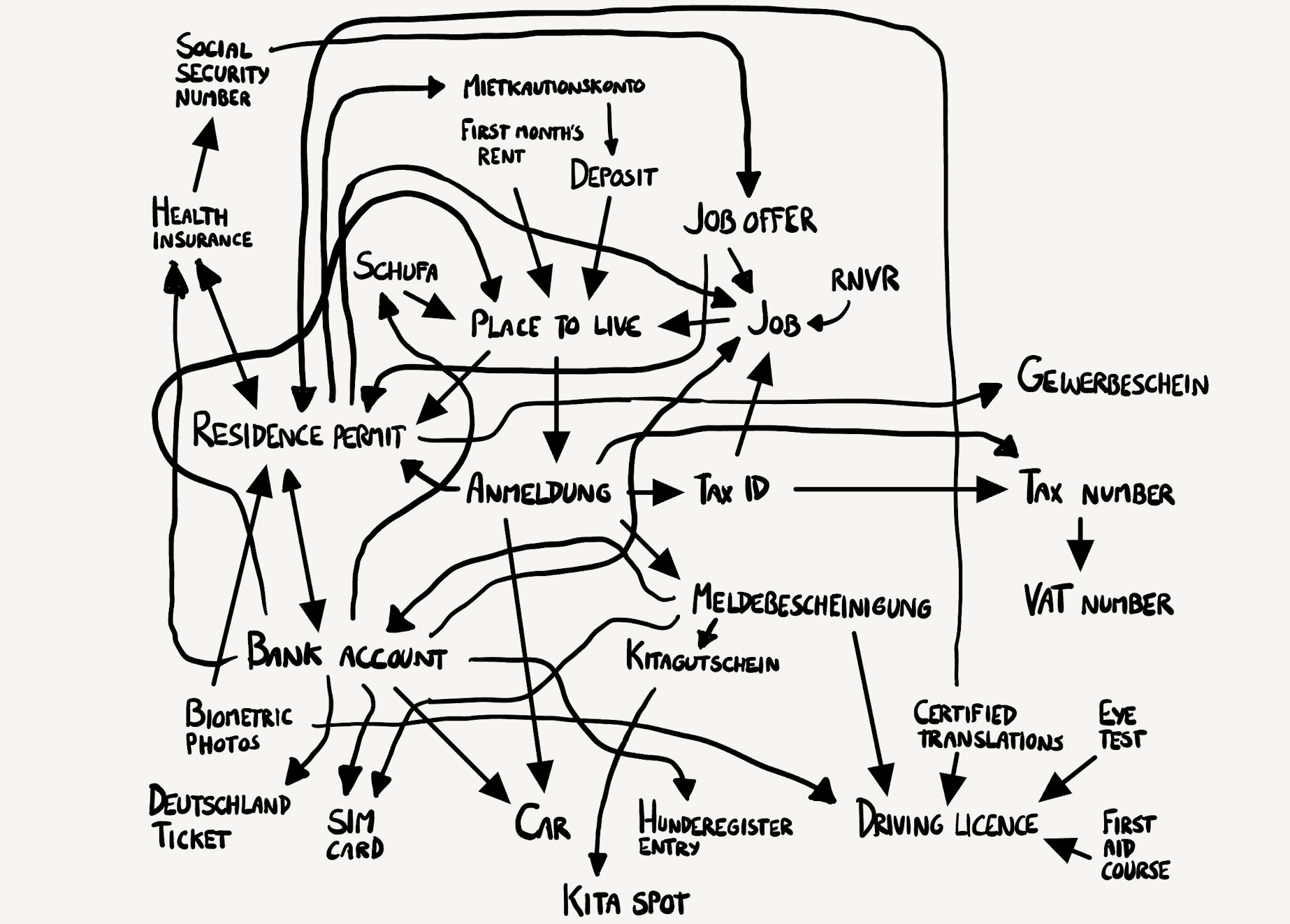

To make things worse, there are many catch 22 situations. Circular dependencies that only immigrants find themselves in.

For example, they need a residence permit to get a job,

…and they need a job to get an apartment,

…and they need an apartment to get a residence permit.

Or they need to pay the deposit to get an apartment,

…and they need an apartment to open a bank account

…and they need a bank account to pay the deposit

These things happens because the systems in place were not designed with immigrants in mind. Their designers made a lot of assumptions about what every adult German resident should have, and those assumptions were wrong.

A big part of my job is to find and document workarounds for the deadlocks that result from those assumptions.

For example, what do you do if you can’t open a bank account because you can’t get a tax ID

…because you can’t register your address

…because you can’t find an apartment

…because the housing market is fucked

…and your AirBnB won’t let you register?

Good information matters

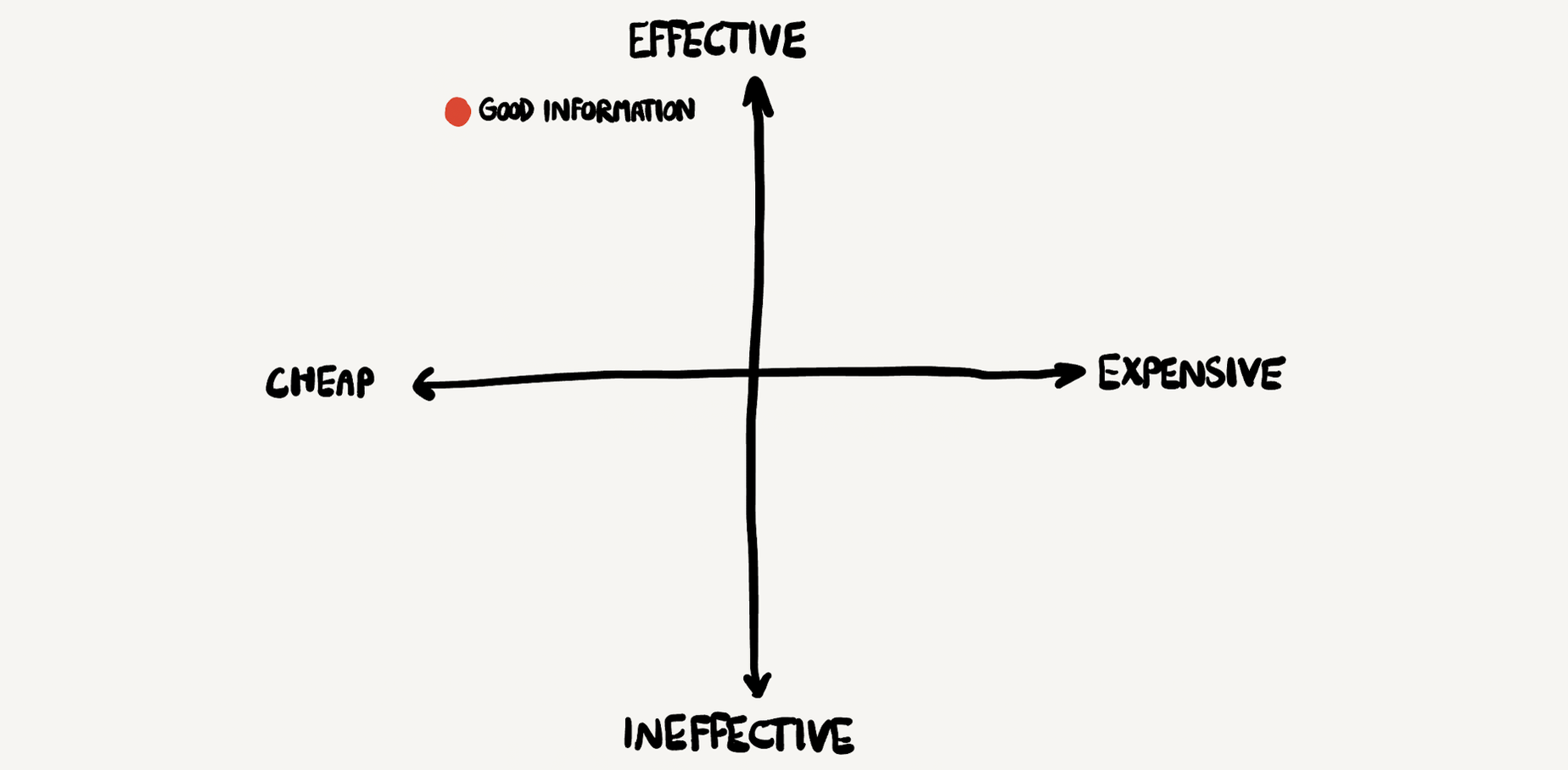

My solution is good information. If you can’t change the outcome, at least you can change the experience. Good information makes the experience more predictable, and that makes people feel a lot better about it.

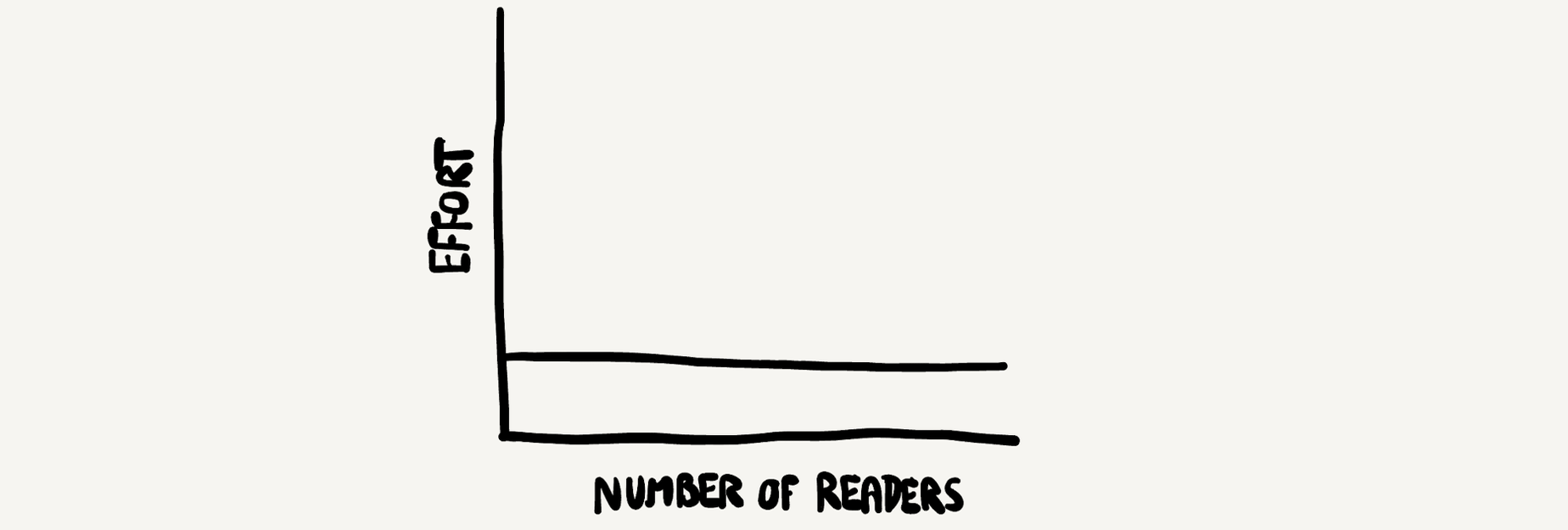

The best thing about information is that it’s really cheap. A single person can run a website that serves hundreds of thousands of visitors per month, and host it for free. After seven years, my hosting bill is still around 10€ per month.

Second, information scales well. Whether you serve a hundred or a million people, the amount of work is roughly the same. Your impact is only limited by your reach.

For example, I have built an Anmeldung form filler. It helps people feel a complex government form in plain English, with clear instructions and form validation. 45 people use it every day. Over 16,000 people every year. That’s thousands of hours saved, and since it went live, it required almost no maintenance.

When you think about it, good information is disproportionately effective. It’s cheap, it scales well…

…and nobody cares about it. Why is that?

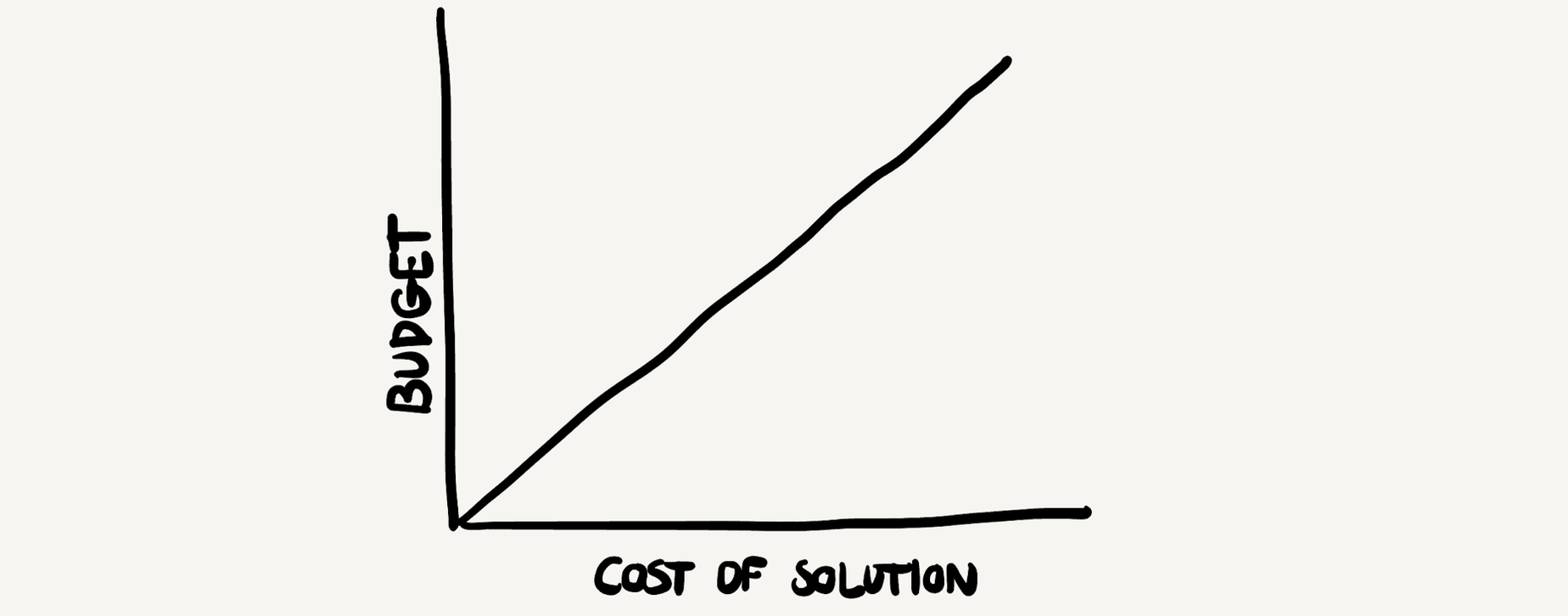

I suspect that people only look for solutions in proportion to their budget. If you have a big budget, you look for big solutions.

But when people focus on big solutions, they tend to neglect the small stuff that brings disproportionate value.

For example, you can spend billions building an airport, but neglect the signage and forget to install water fountains and power outlets. These are the details that people notice and remember.

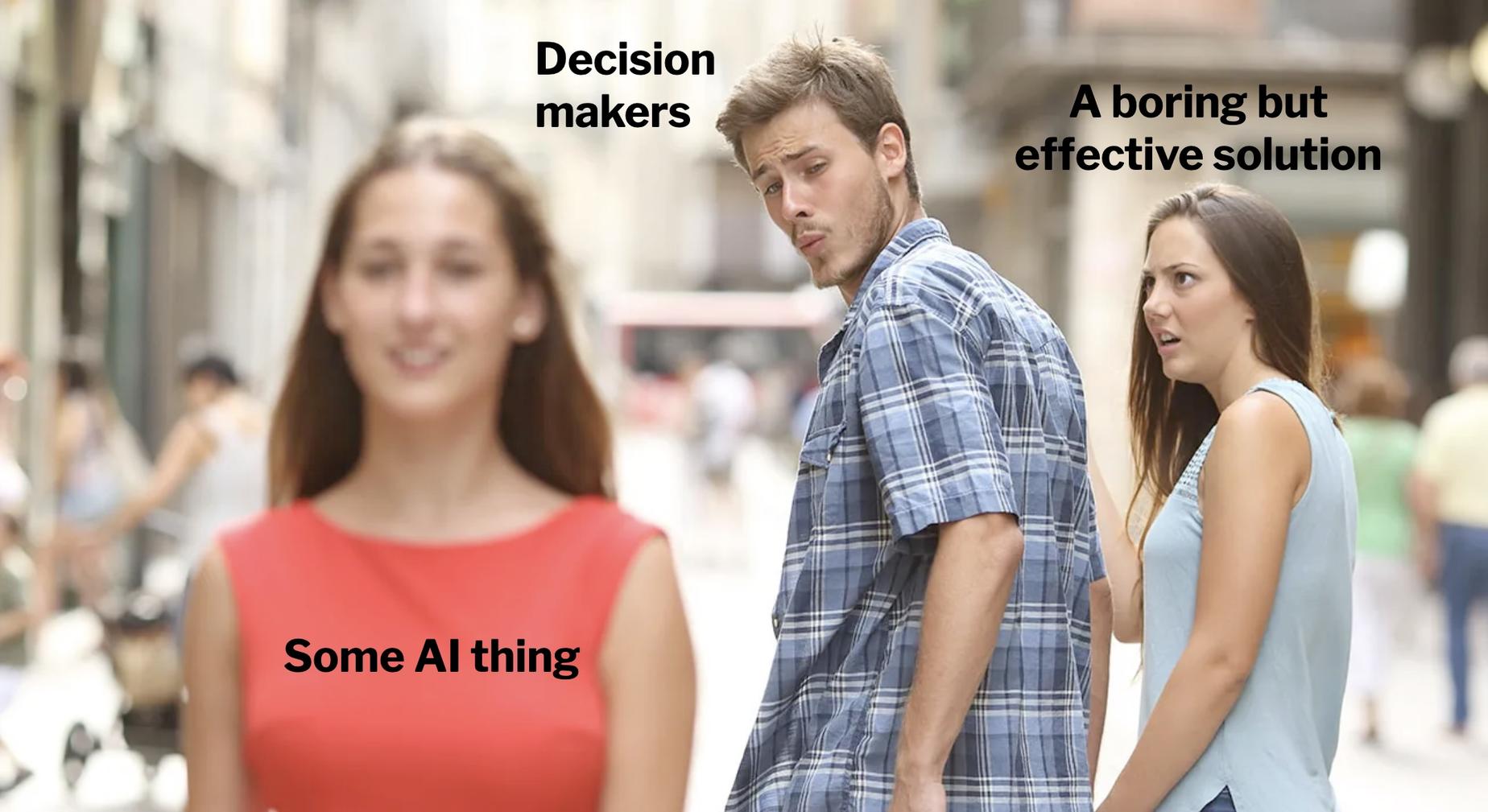

Second, it’s not glamorous. My proposition is to do something boring and obvious, but to do it really well?

You can sell people a chatbot or some AI nonsense. It’s exciting, the press loves it, and it makes you seem like a champion of innovation. It doesn’t even need to work!

But nobody reports on boring solutions. They don’t get people promoted. Nobody gets a startup award for running a blog or putting up signs in an airport.

But the boring details are important too. Sweating the small stuff shows that you care, and it makes people feel noticed.

How to create good information

So how do you create good information?

1. Get inspired

Most of my guides are based on personal experience. I wrote about moving to Germany because I am an immigrant myself. I’ve been there. I’ve done that. I know how it feels. I remember the exact moments when I got angry, confused, or discouraged, so I can navigate people through it.

I do it out of a duty to document. I figure that if information is cheap and disproportionately valuable, and it only takes a few minutes to put text on the internet, and it can help thousands of people, it would be selfish to keep it to myself.

Otherwise, there is no grand plan. I mostly follow impulses and work on whatever feels useful or interesting at the moment.

Sometimes my work is all cut out for me. Sometimes I just go around the website rephrasing things and adding details. Sometimes I wake up, have a strong coffee, and see where it takes me.

What I don’t do is cover news and current events. These things change too quickly and I don’t have the manpower to cover them. I’ve made that mistake twice.

Once during COVID. I started documenting changes to COVID restrictions - in plain English - because no one else would do it. I thought it would only last for a month or two. I ended up maintaining that stupid page for almost 3 years.

The second time after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. I tried to corral all the locals willing to help refugees by funnelling their goodwill toward existing organisations, so that they wouldn’t all try to save the world on their own.

I try to focus on evergreen content that can be steadily improved over time, instead of ephemeral articles that quickly fade into irrelevance.

2. Think about it super hard

The next step is to fully understand the problem, and to come up with a basic guide structure.

Most of my guides follow the same basic structure:

- What is this process?

- Why is it important?

- Who qualifies for it?

- How is it done?

- What comes next?

- Where to find help?

When I say “why”, I mean why it’s important to the reader. Bureaucracies have a tendency to explain things from their perspective. They tell you what they want from you, and never bother justifying it. “Make an appointment, bring us these documents, and pay us 50€. Do it because we said so.”

When I write, I try to justify things from the readers’ perspective. Why should they care? What do they get in return? How does it fit with their goals? What happens if they don’t do it? People are a lot more likely to do the right thing if they know why.

Then I try to explain how the process goes, once again from their perspective. What are their needs? What are they uncertain about? What scares them?

Usually, people want to know how long it will take, how hard it’s gonna be, how to prepare, and exactly how to get the required documents. The official website never explains those things. “Here’s a list of documents. Good luck.” The rest is left as an exercise to the reader.

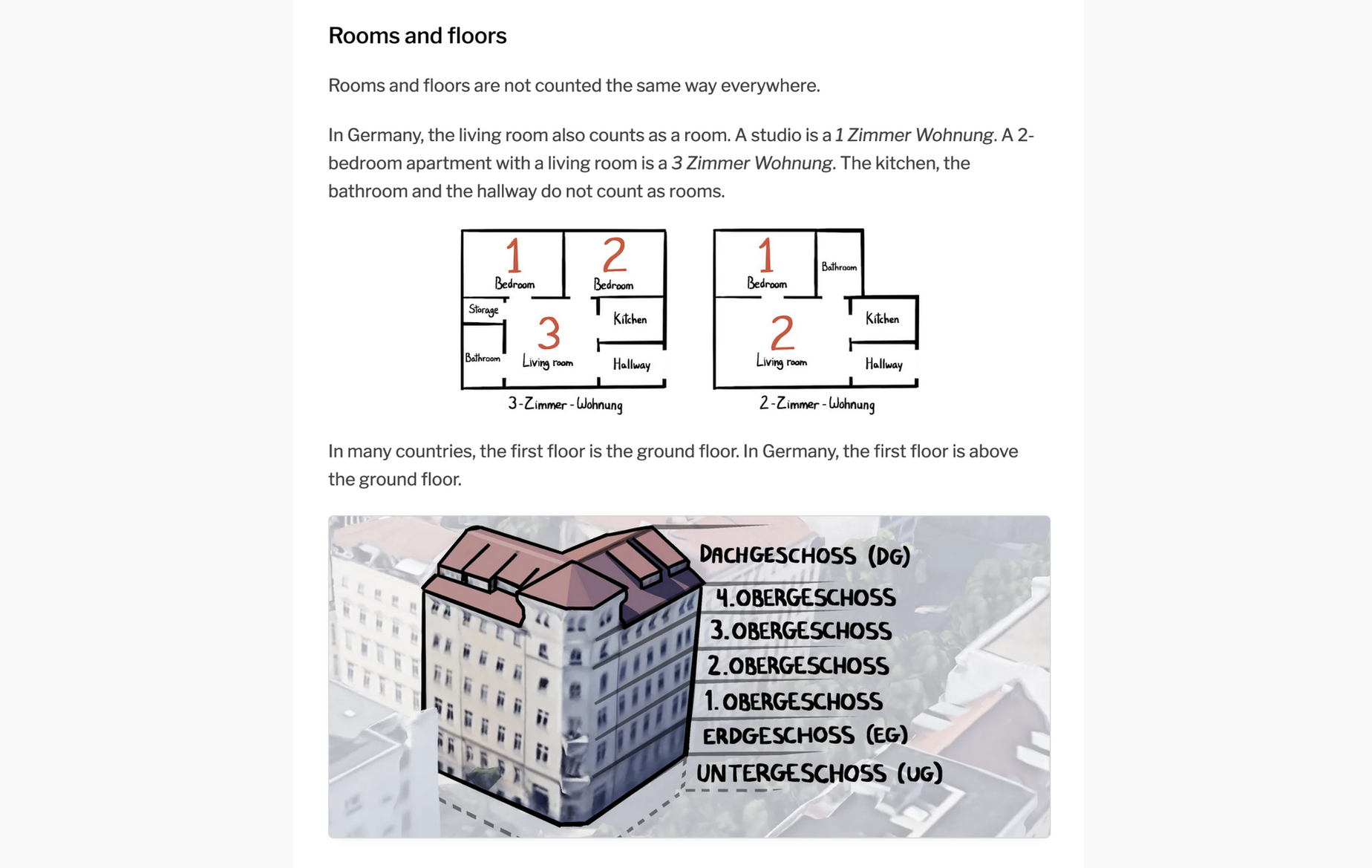

I also try to find out which of their cultural expectations don’t apply in Germany, and how the language barrier affects their experience. The most banal aspects of German culture can take immigrants by surprise.

At last, I offer people ways to get help. I would love to help everyone individually, and I do answer every email that comes my way, but it’s unsustainable. I used to get dozens of emails a week - far more than I could answer - so I have to redirect readers to a curated list of experts.

3. Research

Once I know what I want to write about and which questions I need to answer, I start researching the topic in depth. This is the hardest part of my job.

Usually, it involves a lot of reading. I start at a high level with news articles, then I work my way down until I reach legal texts and court cases.

This is the ground truth.

Once I know how the system should work, I focus on how the system actually works. The discrepancy can be significant.

I read hundreds of social media posts to learn about people’s experiences. I reach out to some of them with questions. More and more, I also survey my audience on social media. Recently, I started creating task-specific group chats with my readers to ask them quick questions.

I also ask the city directly, but it’s not nearly as effective as one would think. I write to all 12 districts, get 6 responses, 3 of which contradict each other. Steglitz does it one way, Pankow does it another. Wedding misses the point entirely. Mitte replies 2 months later. And that’s just within Berlin! Each state interprets the law completely differently, so advice that applies to Berlin does not necessarily apply to Munich.

This is why it’s so important to ask around. It gives me an idea of how much variance there is in the process. I can’t always give people a precise answer, but even documenting the range of possible outcomes is valuable to my readers.

4. Writing and editing.

Next comes writing. I write clearly and concisely, in plain English. I put a lot of work into it. I can revise the same paragraph over and over again to get my point across succinctly.

People are busy and stressed. Some speak English as a second or third language. I want to use their limited attention for what matters. I skip intros, conclusions and pointless commentary. I aim for the maximum signal to noise ratio.

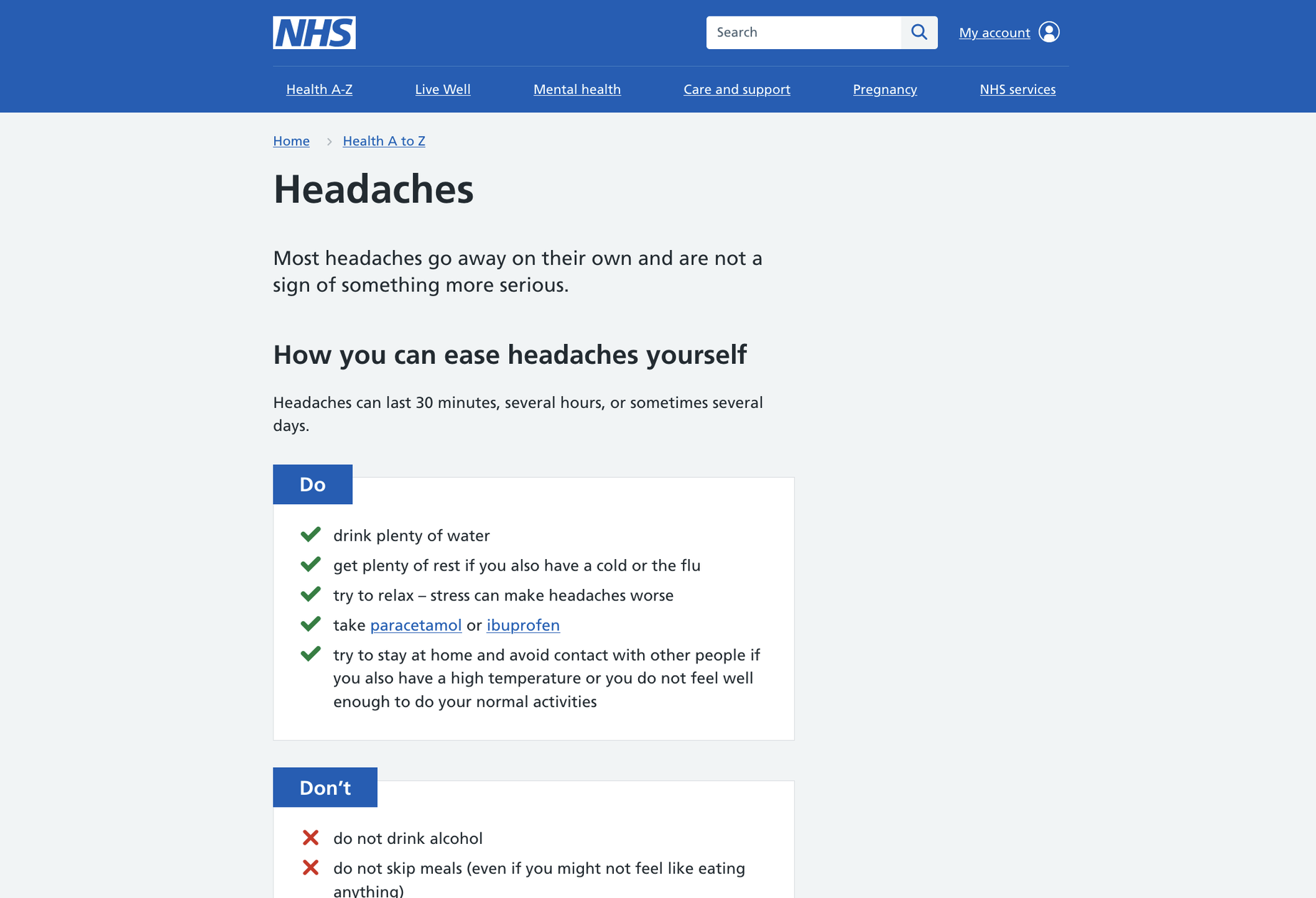

My content is meant to be skimmed. I know that people won’t read the whole thing from top to bottom, and that’s okay. I use clear formatting to guide them to what they want to know. Basically, I design my website to be the opposite of every recipe website ever.

I draw a lot of inspiration from NHS.uk. It’s a wonderfully straightforward and well-written website. Most UK government websites are.

Just go to their website, and look up a random symptom. See just how clear, helpful and reassuring the information is. Not a single word is wasted. It’s beautiful.

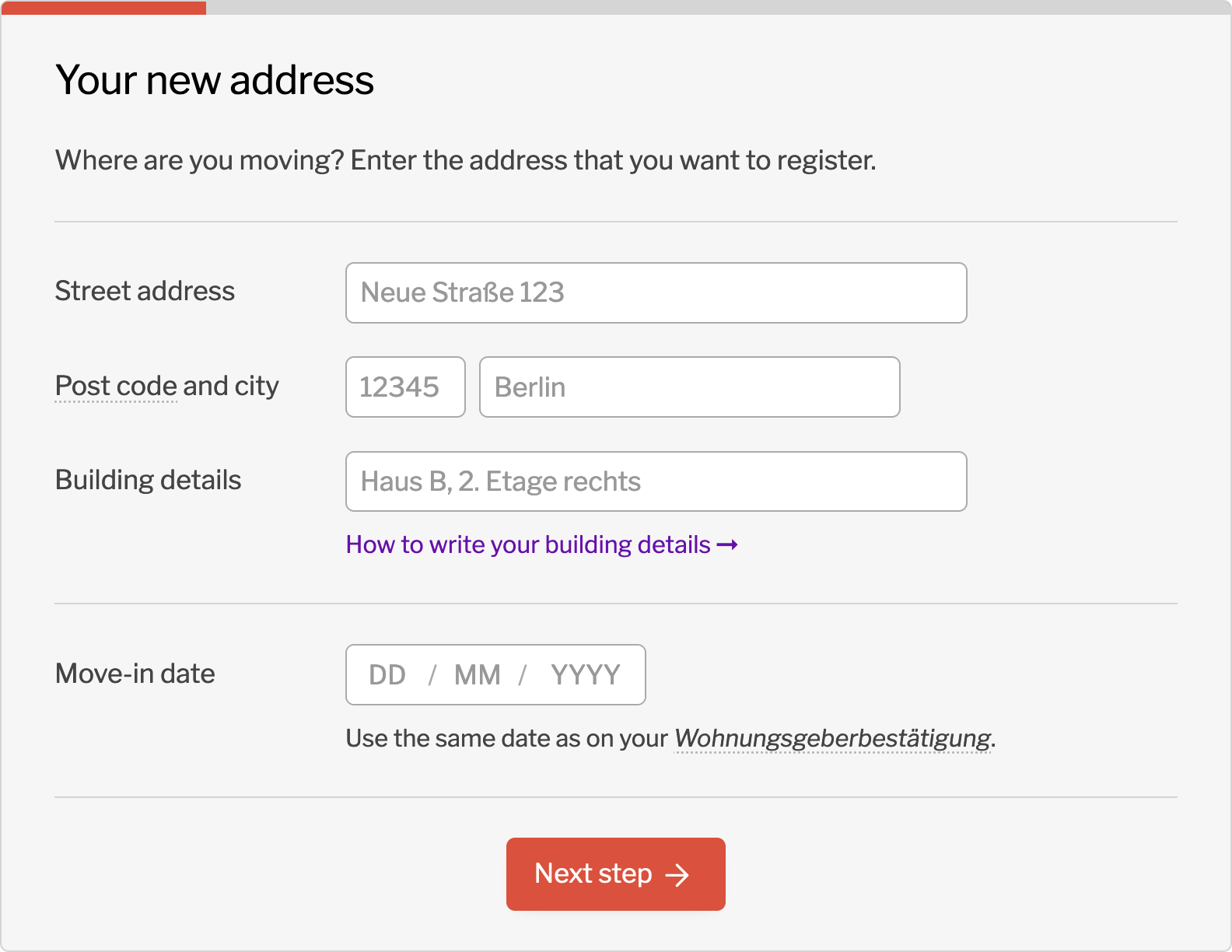

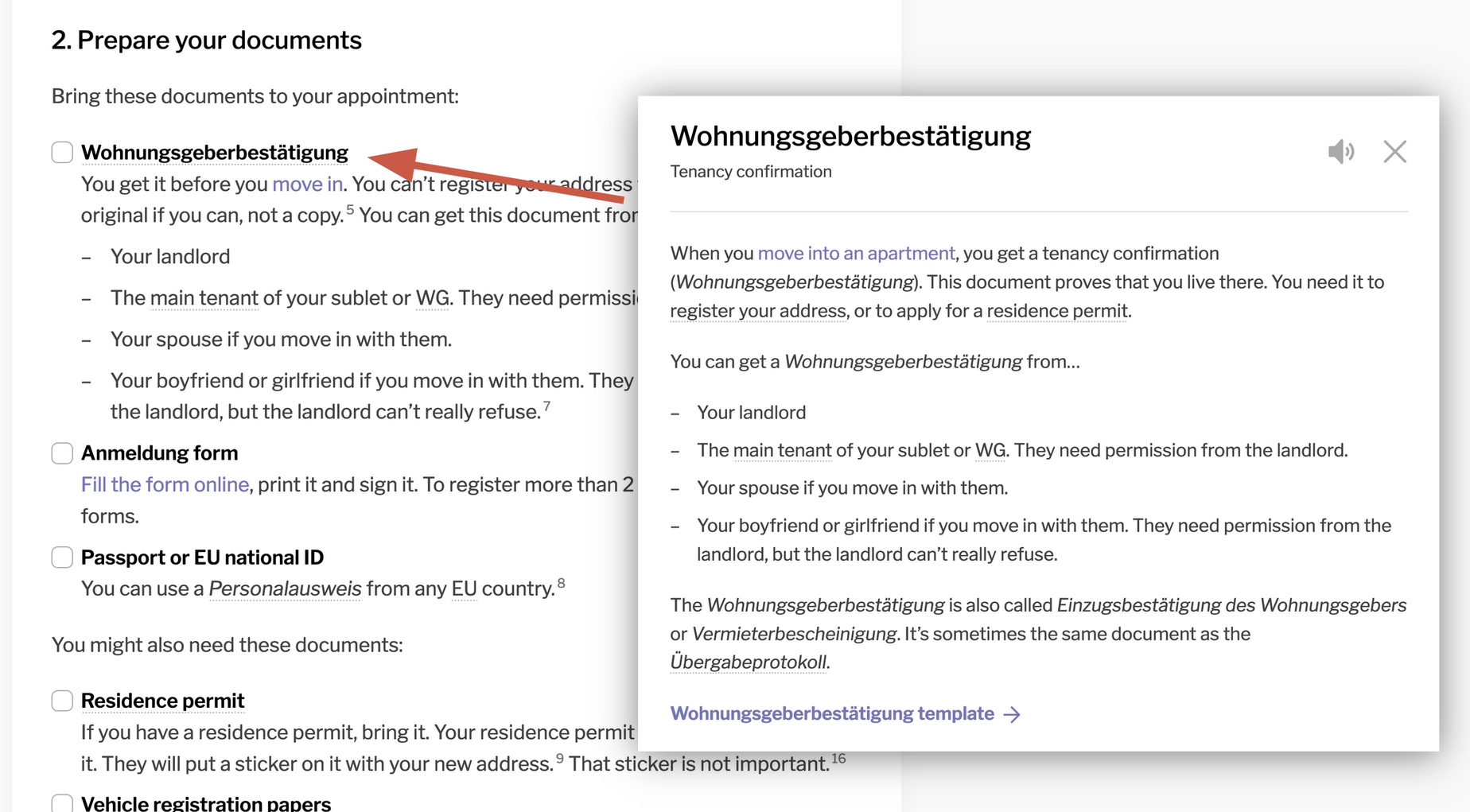

When I write, I assume that my readers have no prior knowledge. I imagine that they landed in Germany yesterday, speak no German, and definitely don’t know what a Wohnungsgeberbestätigung is.

That’s why I explain everything that needs explaining. Nothing is too obvious. If the explanation is too long, I move it to a glossary pop-up, or turn it into a separate guide. People who need it can read it, but it doesn’t get in the way.

I use images sparingly, but I create my own graphics when they can be helpful. I release most of them in the public domain.

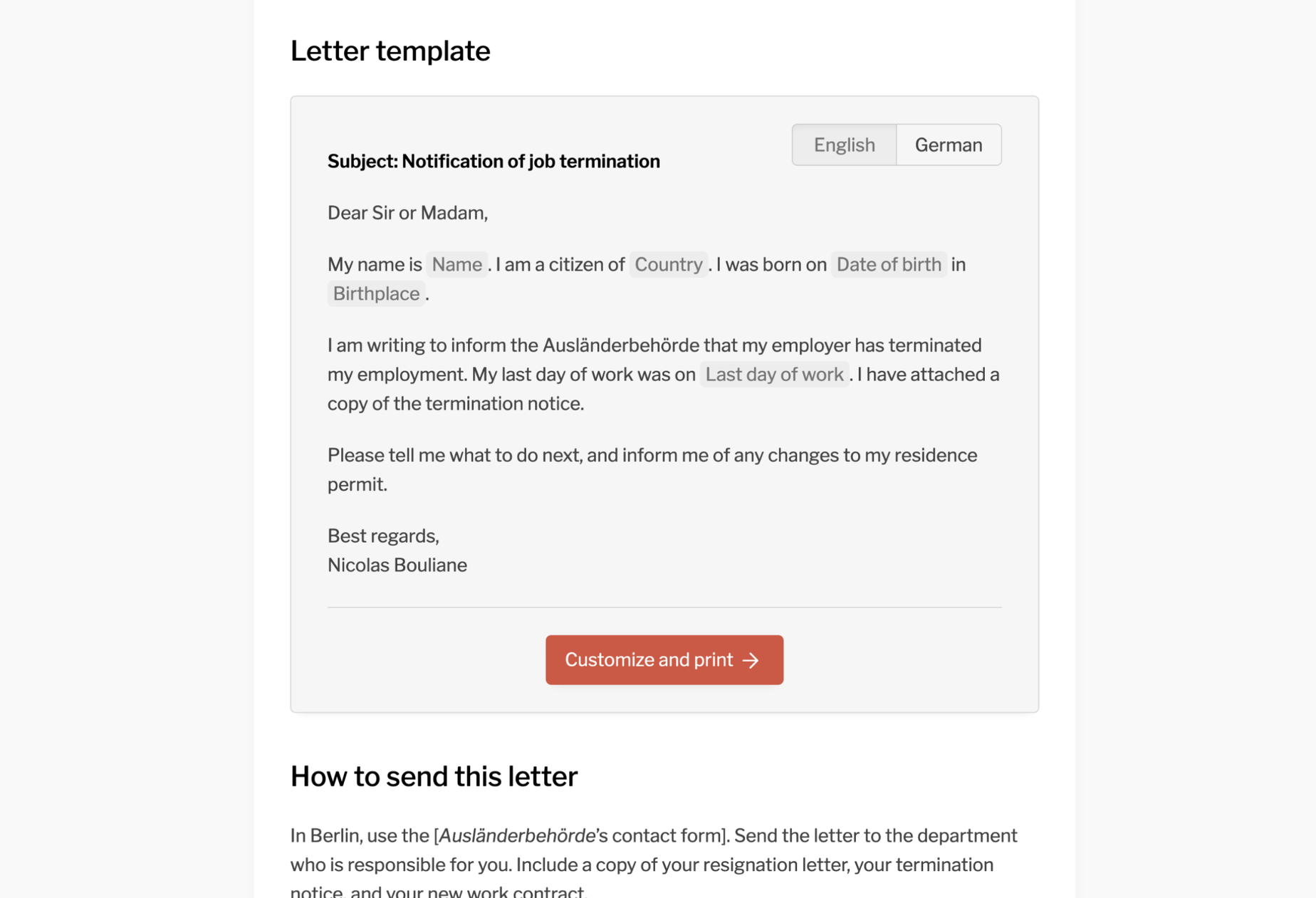

I also create my own letter generators. Writing a letter in a foreign language is a daunting task for many. It adds friction and makes people procrastinate or give up. My letter generators show the letter in English and German, and let people fill in the blanks. They get used thousands of times per month. That’s hundreds of hours saved!

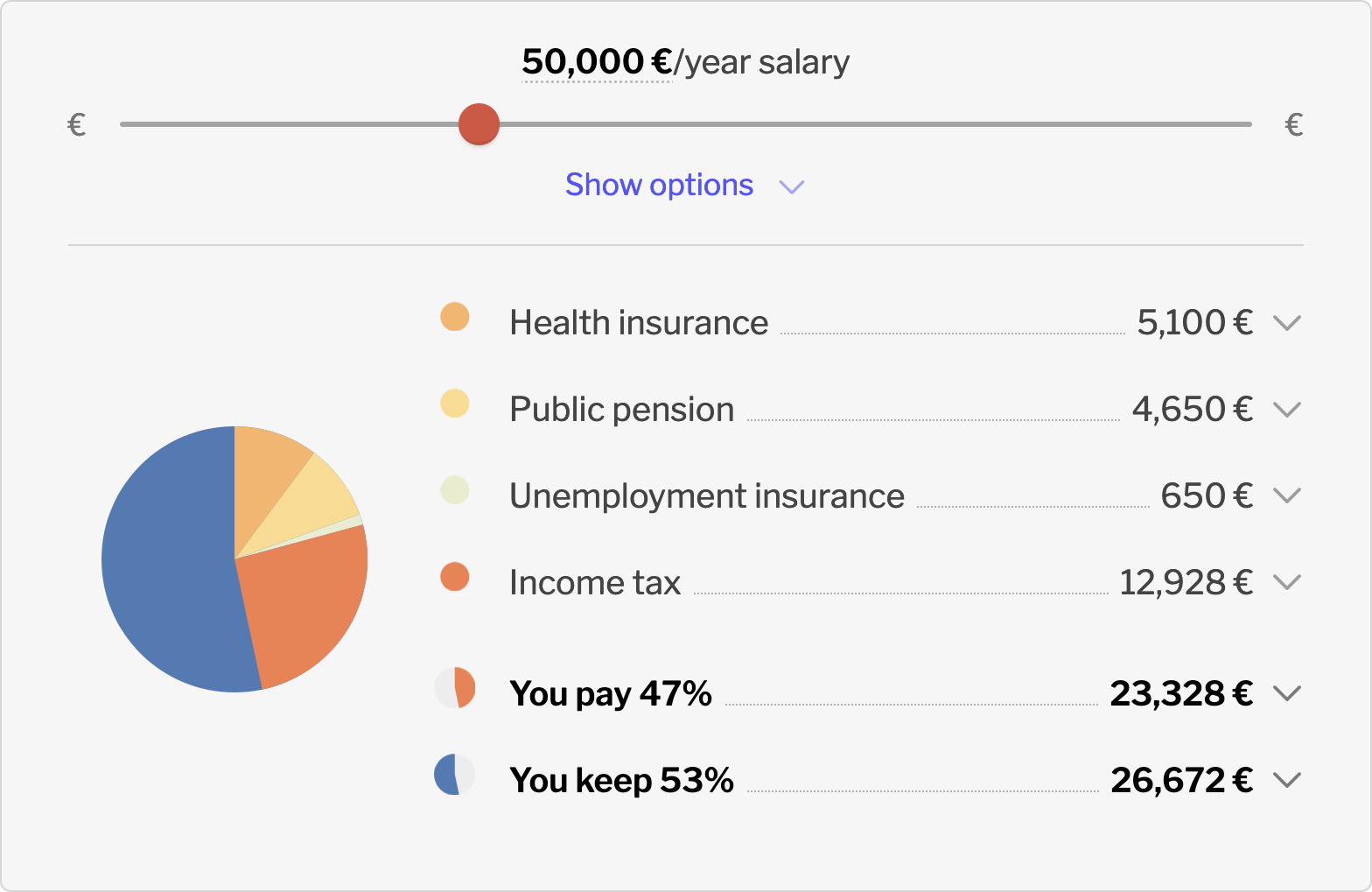

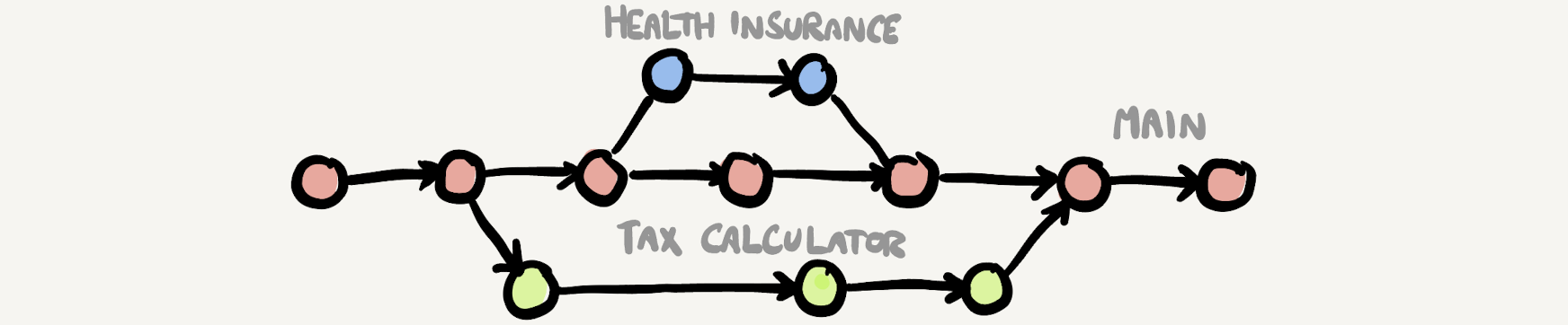

When explanations get too complicated, I create calculators or tools instead. This is a tax calculator I have made a few years ago:

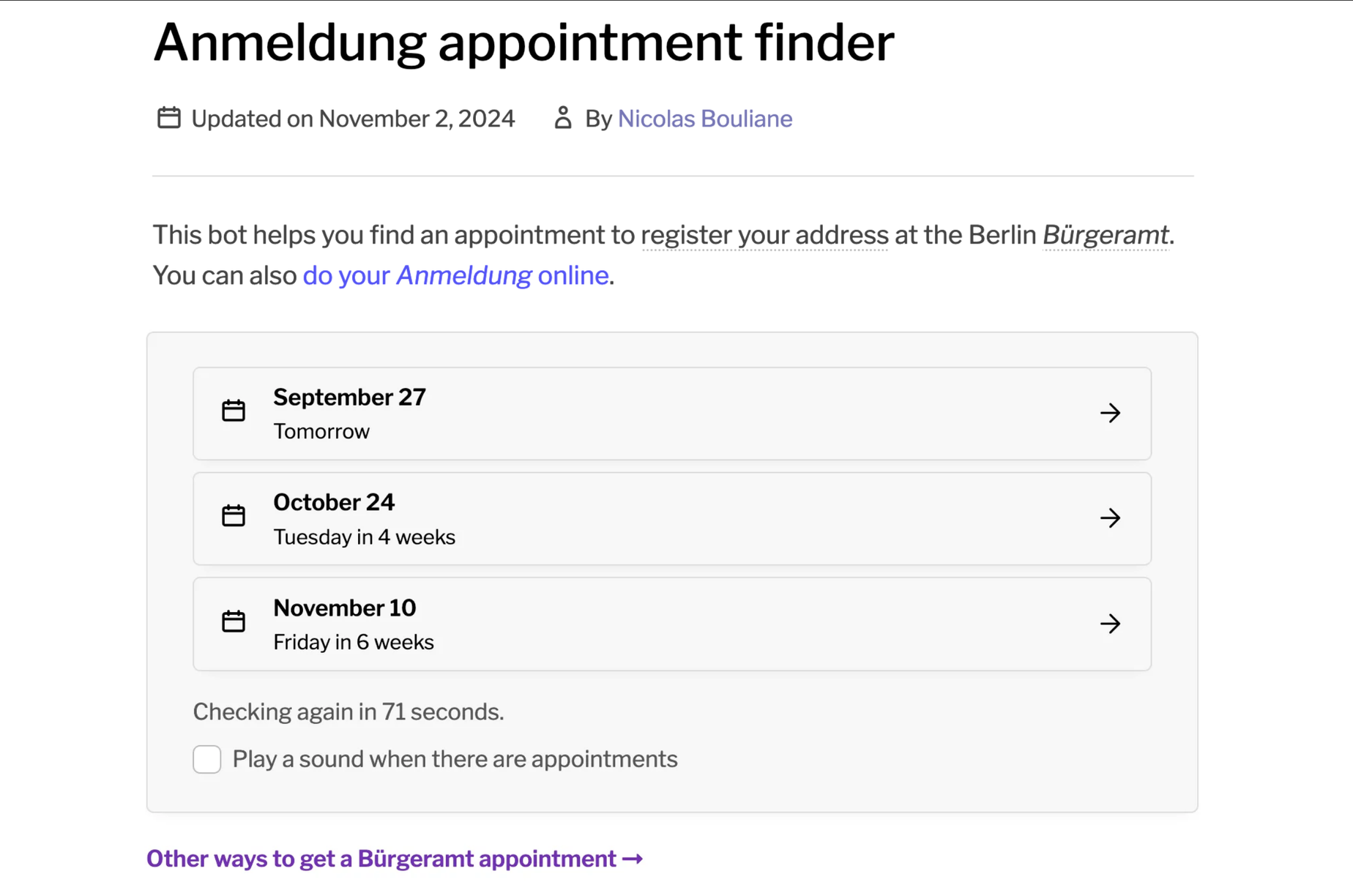

I also created a tool that helps people find Bürgeramt appointments. It might not reduce uncertainty, but it reduces friction, and that’s just as important.

5. Release

All About Berlin’s content is under source control, so I can work on different things at the same time. For example, I can make all sorts of small changes on the main branch and work on a new series of guides in a separate branch.

When my work is ready, I merge it into the main branch and deploy it.

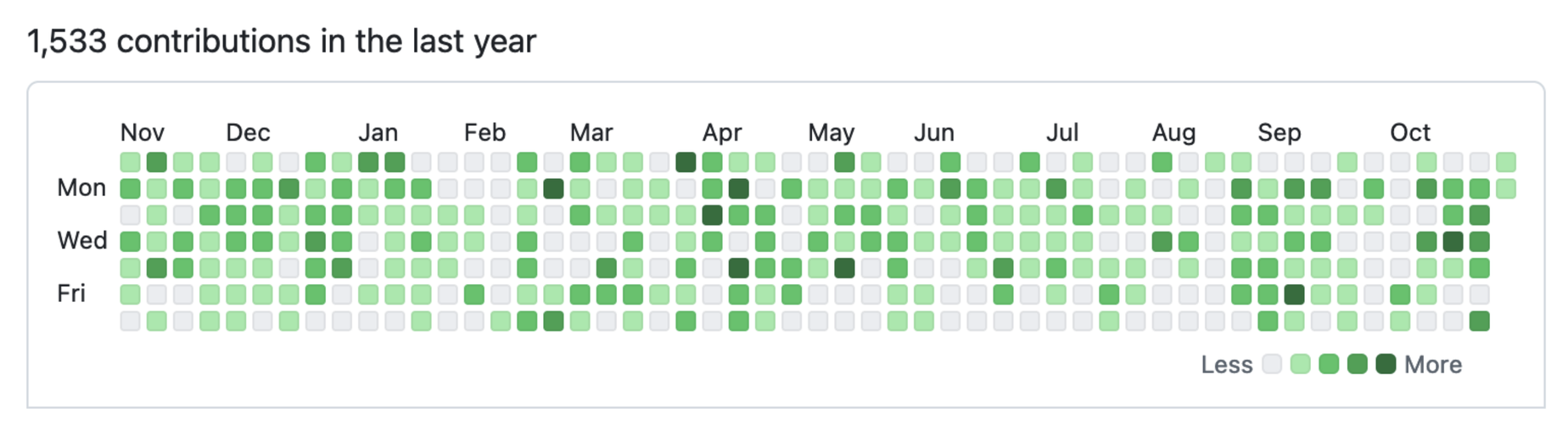

Some tasks bring hundreds of little changes to dozens of pages.

After the release, I follow a post-release checklist. The first day mostly involves telling a lot of people what I just did and bringing attention to my work. I also try to involve experts in a final round of revisions, and make sure that every little detail is done right.

I also release the by-products of my work. I open source as much code as possible. I really wish I could open source the website itself with all its content. It would open things up to contributors. However, the hostile nature of the web means that illicit copies of the website would spring up within a week.

6. Maintenance

The last step is by far the most important one: maintenance. Each guide I release is a commitment, a liability. It’s not something that I just publish and forget.

For every new guide that I write, I make hundreds of changes and refinements to existing ones. The website grows a bit like a tree; it develops new branches, but the existing ones slowly grow thicker and sturdier.

I have set up a lot of infrastructure to keep my guides up to date. I monitor hundreds of pages and legal texts for changes with Wachete. When a law or a government service changes, I get an email that shows exactly what changed. I usually update my content within a few hours.

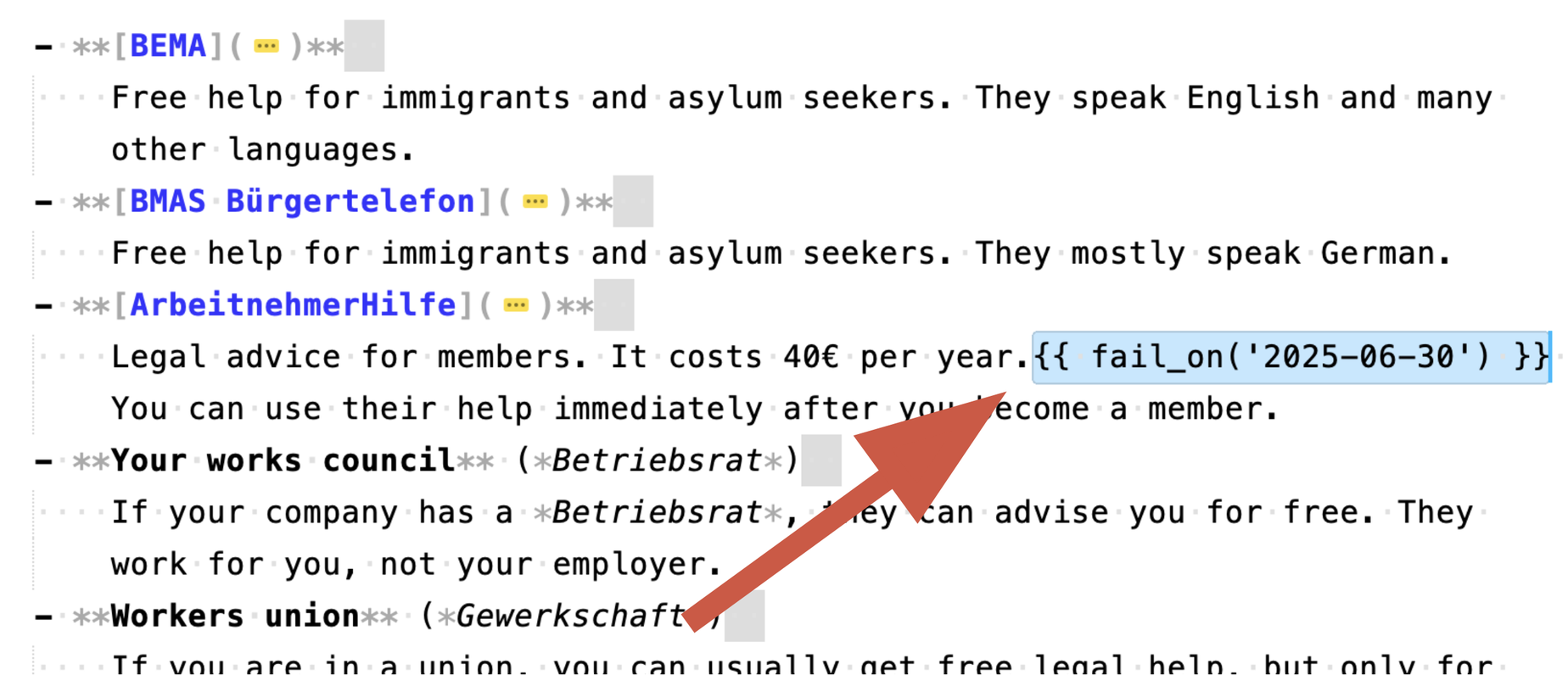

Behind the scenes, I also set expiration dates on parts of the content. This bit of code triggers an error after a certain date. The website won’t build until it’s fixed. It’s a reminder to check if statements are still correct after a while.

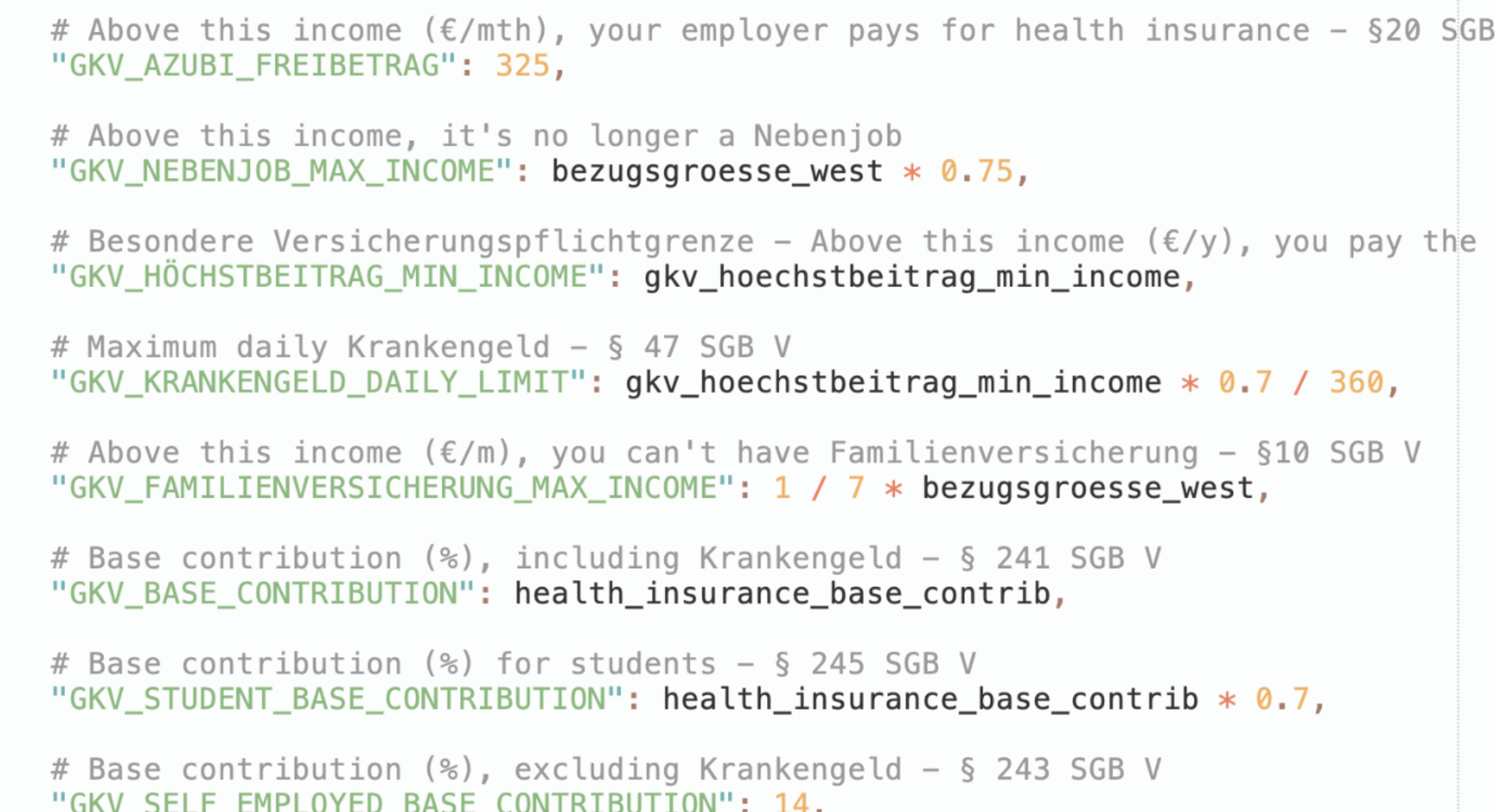

I use hundreds of constants. When I change one, the changes automatically propagate to the entire website. If I update the minimum wage, it triggers changes in a bunch of guides, and updates a few other values that are based on the minimum wage, such as my health insurance calculator. Combined with change monitoring on relevant pages, I can update the entire website the same day a law changes. This is useful in January when all sorts of federal laws are updated at once.

To make my research easier, I have created a WhatsApp community of immigration experts. There are a few dozens of us in there. We share knowledge and updates and discuss the finer details of immigration law. It costs us nothing to join and participate, but it saves us an awful amount of time.

Trawling social media for relevant information is getting a bit time consuming, so I try to get better at directly collecting feedback from my users.

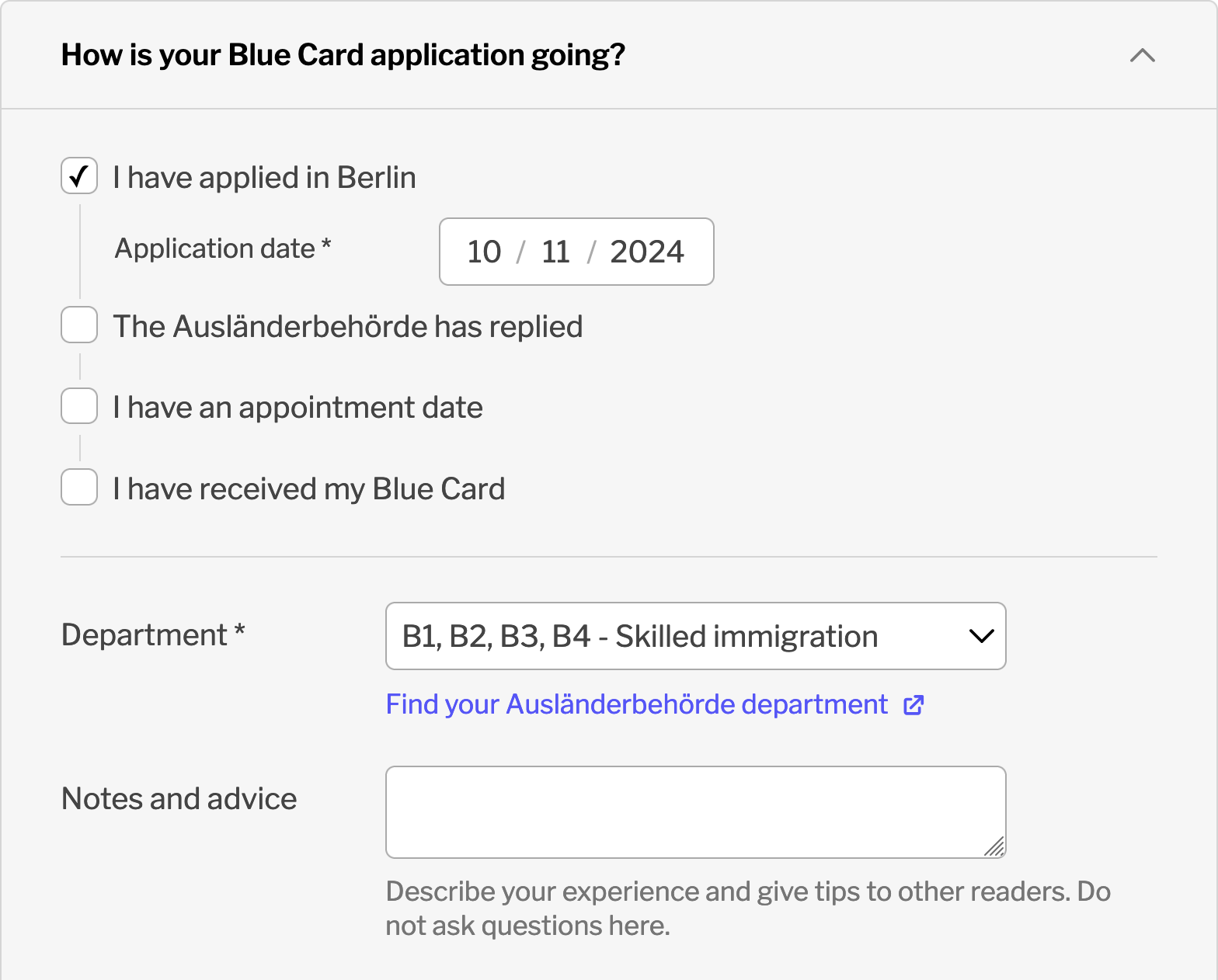

I have just released a tool that measures the wait times at the immigration office. It collected around 50 data points in its first week, more than I’d usually find in a whole year.

This is a game changer. My hope is that we can get something like this

But for a journey with much higher stakes: settling in Germany.

A digital garden

This emphasis on maintenance is a radical idea on an internet dominated by streams, where everything is ephemeral.

Someone asks a question on Facebook. Another answers. A day passes, and the question flows past everyone. Two or three days later, it sinks at the bottom of everyone’s feed, lost in the abyss. A week later, someone asks the same question again. Rinse, repeat.

I see my website more like a digital garden. I spend most of my days tending to it, walking around my garden, plucking dead links, pruning superfluous words, and re-potting overgrown paragraphs into their own guides.

I neglect some sections and obsess over others like any gardener, but my advice does not get lost in the depths of the internet. It persists and it grows. It bears fruit for others to enjoy.

And above all, little by little, my little garden does something wonderful: it transforms the landscape.