Support networks

Posted onI had drinks with a Spaniard in Malaysia. He moved to Malacca years ago to start a tapas restaurant with his wife. As we sat by the street, watching the humid air condense on our beer glasses, we started talking about the logistics of running a restaurant there. He described the the difficulty of hiring and training the local staff to his foreign standard.

He struggled with the Nepalese migrant workers that made up half of his staff. These boys, he explained, were dropped at the airport by their agency and left to fend for themselves.

When they had problems with money or health, with loneliness or the family back home, they’d turn to him and his wife. He was unexpectedly thrust into the role of a father figure for half a dozen boys. He truly had to run the business like a family, with all the drama it involved.

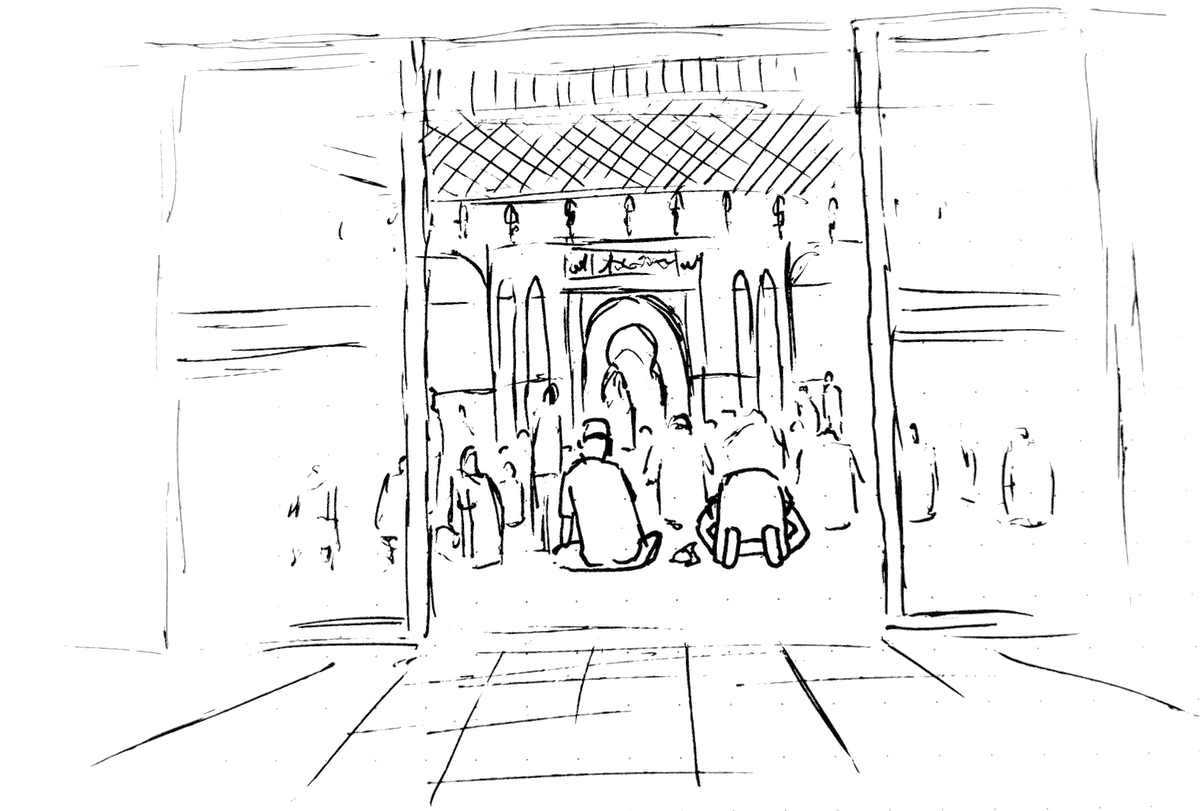

More interestingly, unlike the Nepalese, he continued, the Muslim migrant workers fared much better. When they arrived in Malacca, the local mosque would soften their landing. There, they could find community, a place to spend time, and people to help them. They had a support network. The Nepalese workers did not.

I help immigrants for a living. I am keenly aware of how it feels to move somewhere without a support network. Yet I was completely oblivious to the oldest support network in the world: religion. I could talk somebody’s head off about third places and social infrastructure, but it never occurred to me that mosques could be examples to learn from.

There is value to congregating with your neighbours every day. In every discussion about the loneliness epidemic, commenters will remind people of the Church’s role in their community, and what is being lost with its fading relevance.

It leaves me thinking about my role in my community. For the last few years, I have focused on creating a resource for Berlin’s immigrants, but I should also have been building a community. Going forward, I’d like to develop the sort of social infrastructure to bind this community together.