The Berlin airlift

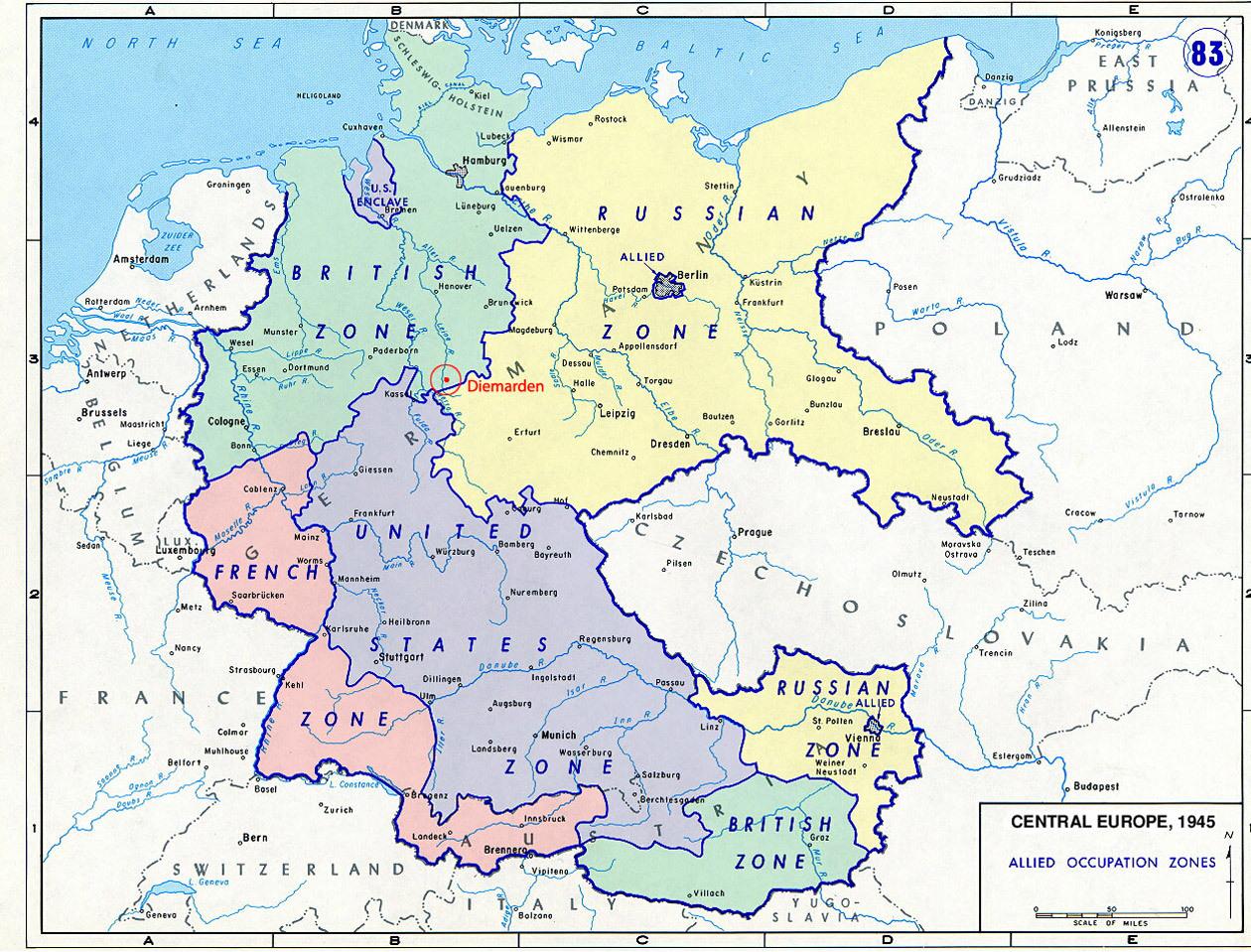

Posted onShortly after the end of the Second World War, the victorious Allies met in Potsdam to organise the administration of post-war Germany.

Its territory would be divided in four occupation zones controlled by the United States, Britain, France and the Soviet Union. Even though it sat about 160km into the Soviet sector, Berlin would also be split in four. The German capital would only be accessible to the Western Allies by air and through narrow road and rail corridors.

The Americans and the British quickly realised that a stable and productive Germany was essential to Europe’s economic recovery and shifted their policy accordingly. The American, British and French zones were merged into what would become West Germany, and the United States extended its Marshall plan to also support the new trizone.

Tensions arise

The Soviets strongly opposed these measures. After suffering devastating losses in the Second World War, they had no interest in seeing their former enemy rise again. Moreover, Stalin feared that these western policies would erode the Soviet Union’s influence in Germany, which he intended to be Soviet-controlled and communist.

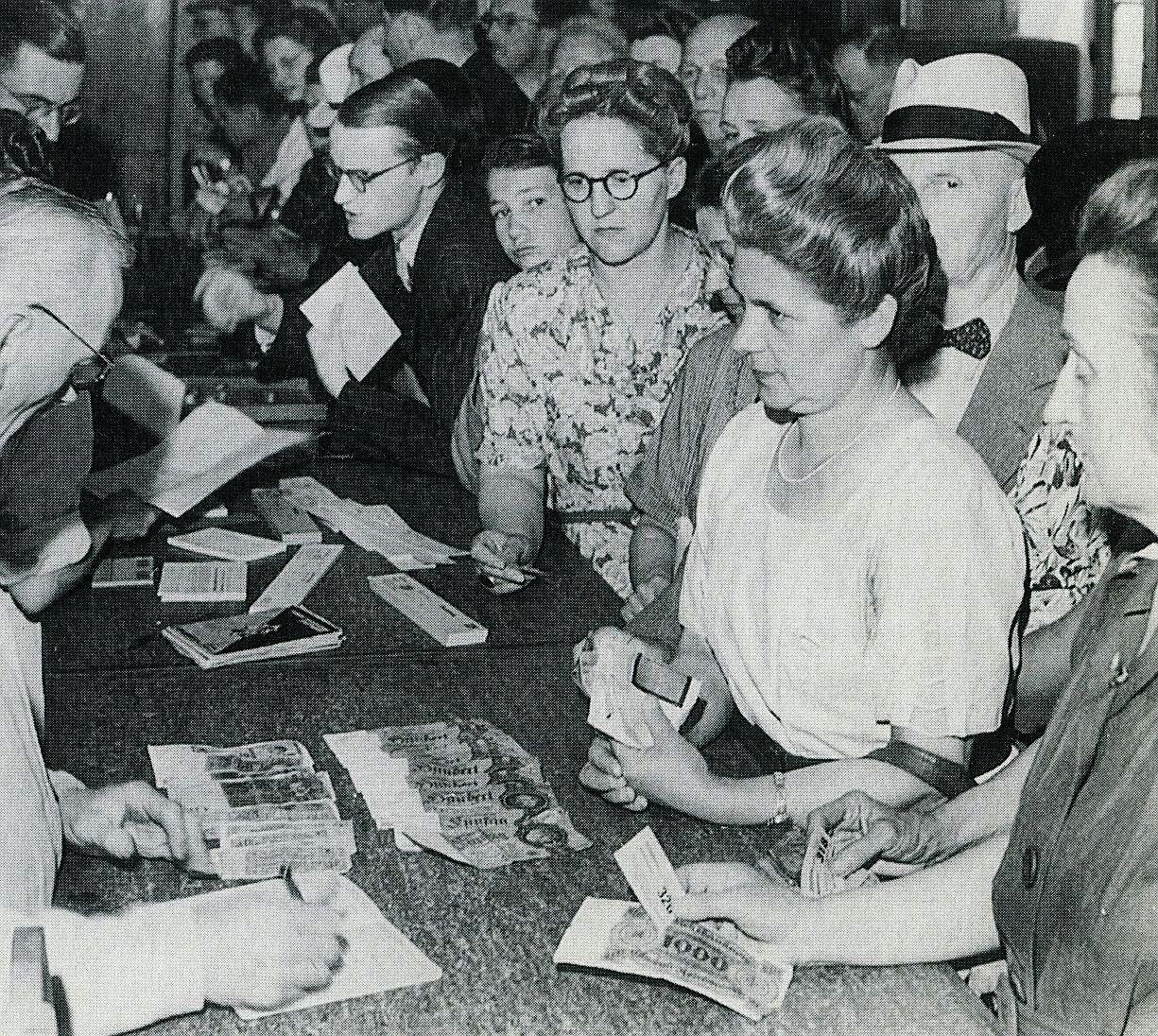

On June 21, 1948, the Deutschmark was introduced in West Germany to replace the over-circulated Reichsmark. The old currency was so debased that people bartered goods and used cigarettes as currency.

A day prior, American military lorries had delivered 23 000 crates labelled “doorknobs” all over West Germany. These actually contained a total of 10.7 billion freshly printed Deutschmarks. Each West German received 40 Deutschmarks, and could trade in their old Reichsmarks for the new currency.

Since the Reichsmark was still legal tender in the Soviet sector, the old currency flooded into the east, further devaluing it for East Germans. In Berlin, the Deutschmark became the de facto currency, even in the Soviet zone.

Stalin considered this move a provocation, and wanted the West completely out of Berlin. The Soviets completely shut down access to Berlin. All rail, road and water traffic was halted immediately, and Berliners were left without food or electricity supply.

Stalin rejoiced, believing the Western powers had no choice but to abandon Berlin. However, four days later, president Truman confirmed that backing out was “out of the question”.

“We can haul anything”

The greatest airlift in history began with an innocuous phone call. “Could you haul some coal up to Berlin?” asked General Clay to Curtis LeMay. “Sure. We can haul anything”, replied the Air Force general.

The only way to supply Berlin from West Germany was by plane, and it was no small task. In order to feed West Berlin’s 2 million inhabitants, 1 500 tons of food would have to be flown in daily. An additional 3 500 tons of coal would be needed as fuel. By comparison, the previously-largest airlift to supply China over “the Hump” only averaged 500 tons a day.

Only 96 twin-engined C-47 Skytrains were immediately available. At maximum capacity, these could bring in 300 tons of cargo a day. Avro Yorks and Dakotas from the Royal Air Force could be flown in from Britain and increase the airlift capacity by 750 tons.

Fortunately, the US Air Force could scramble an additional 447 four-engined C-54 Skymasters “in extreme emergency” to West Germany, bringing the airlift’s total capacity to an impressive 5000 tons per day; enough to feed Berlin by air. The Berlin airlift was a go.

A day after the Soviets cut the food supply to West Berlin, the first C-47’s landed in Tempelhof with 80 tons of cargo. The airlift averaged 90 tons in the first week, then 1000 tons the second. At that time, the operation was not expected to exceed three weeks.

“You cannot abandon this city”

Despite the overwhelming praise for the operation, the crews were dangerously overworked, and the planes were falling behind on maintenance. Moreover, with the airlift nowhere near its expected capacity and the food stockpiles dwindling, West Berlin was risking starvation. The Soviet press ridiculed “the futile attempts of the Americans to save face and to maintain their untenable position in Berlin”.

There was also some interference from the Soviets, whose fighters harassed Western transport airplanes. “They’d come up individually, buzz you head-on and then at last-minute pull up and come right over your wing. At first, we didn’t know whether they were going to shoot or not.”

Berliners, however, pleaded the West to keep up the fight. “Look at this city and see that you cannot abandon this city and these people”, pleaded Berlin’s mayor in front of half a million citizens.

General Clay seized the microphone, and boasted that “not even another war would drive us out of Berlin”. The West would stand its ground.

Feeding 2 million people by air

When it became clear that the blockade would last more than a few weeks, the Air Force flew in William “Tonnage” Tunner. As the commander of the then largest airlift in history, Tunner was the uncontested air supply expert.

On his first day, Tunner discovered that the crews wasted a lot of time returning with their lunch from the airport terminal. He had jeeps converted into mobile snack bars and had “beautiful German frauleins” bring the pilots refreshments and clearance papers while the planes were being unloaded and refueled. With these changes in effect, a C-54 would be ready for takeoff only 30 minutes after it landed.

Tunner also found that a Skytrain’s 3.5 ton cargo took just as long to unload as C-54 Skymaster’s 10 ton cargo. From September 28 onwards, Skytrains were phased out and only four-engined airplanes were allowed. 40% of all Skymasters in the world were now taking part in the airlift.

These measures, along with the centralization of air control greatly streamlined the airlift operation. After two months of operation, over 1500 flights landed in Berlin every day with enough cargo to supply the city indefinitely.

However, with the winter at the door, an additional 6 000 tons of coal would need to be airlifted daily, more than doubling the amount of cargo. The Tempelhof and Gatow airfields already operated close to their limit and could not support hundreds of additional planes.

French military engineers supported by German crews began the construction of a new airfield in the French sector. Since the city was under blockade, heavy machinery had to be flown in then assembled. Nonetheless, the first C-54 landed at the new Tegel airfield only 90 days later.

Although the aircraft were available, the manpower shortage also proved a serious issue. Luckily, a large number of Berliners volunteered to unload planes in exchange for bigger rations. There was also a large supply of skilled ex-Luftwaffe airplane mechanics available right in Berlin. Pilots from Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa also joined the ranks.

The air force published the daily tonnage figures to encourage the crews to break their own records. A German crew managed to unload a 10 ton cargo in 10 minutes, then another beat them by unloading the same amount in under 6 minutes. This competition resulted with a record 12 000 tons of goods delivered on a single day on April 16, 1949.

At its peak, the airlift delivered more supplies than the trains before the blockade, with a new plane landing every 30 seconds in Berlin. “We can keep on pouring it in for 20 years if we have to”, triumphantly announced Tunner.

The candy bombers

When he was not piloting his C-54, Gail Halvorsen liked to go sightseeing in Berlin, his handheld camera in hand. Only three years after the war, the city still featured gutted out buildings and mountains of rubble.

On his way back to Tempelhof, Gail would always notice children lined up against the fence, watching airplanes taxiing on the tarmac. Feeling for these kids who hadn’t tasted sweets in years, he fished two pieces of bubble gum out of his pocket and gave it to them.

Before returning to his plane, he promised to them that he would drop candy from his airplane on his next trip. One child asked “how do we know what airplane you’re in?”. Gail said he would wiggle his wings.

Using his co-pilot and flight engineer’s candy rations, Gail prepared bundles for the children. “It was heavy, and I thought, Boy, put that in a bundle and hit ’em in the head going 110 miles an hour, it’ll make the wrong impression. So, I made three handkerchief parachutes and tied strings tight around the candy.”

When he flew his airplane over Tempelhof, a group of kids was posted at the fence, waiting for him. “I came in over the field, and there were those kids in that open space. I wiggled the wings, and they just blew up—I can still see their arms”

Uncle Wiggly Wings, as the children came to call him, became a celebrity overnight. More and more children would wait for him around Tempelhof, and Gail began to fear he would get in trouble.

“For two weeks we quit, the crowd getting bigger all the time. And we looked at each other and said, Once more, and that’s all.” The next day, an officer came to him and produced a newspaper with his plane on it. The officer had come to tell Gail General Tunner himself wanted him to “keep doing it!”

The operation grew quickly, with a dozen other planes also dropping small packets of candy attached to parachutes. Soon, American children started sending their own candy to help out, and manufacturers offered the pilots as much candy as they could drop. After news got out that he was a bachelor, Gail began receiving love letters from women all over the world.

“Without hope, the soul dies. And that was so appropriate for the day. In our own neighbourhoods people have lost hope, lost function because they have no outside source of inspiration. The airlift was a symbol that we were going to be there— service before self.”

The Soviet Union backs down

The humiliated Soviet Union began offering West Berliners fresh fruits and plentiful rations if they traded their West Berlin ration for theirs, but few people took up on the offer. The hope demonstrated by the food coming into Berlin was stronger than their hunger, and the principled West Berliners refused to give in.

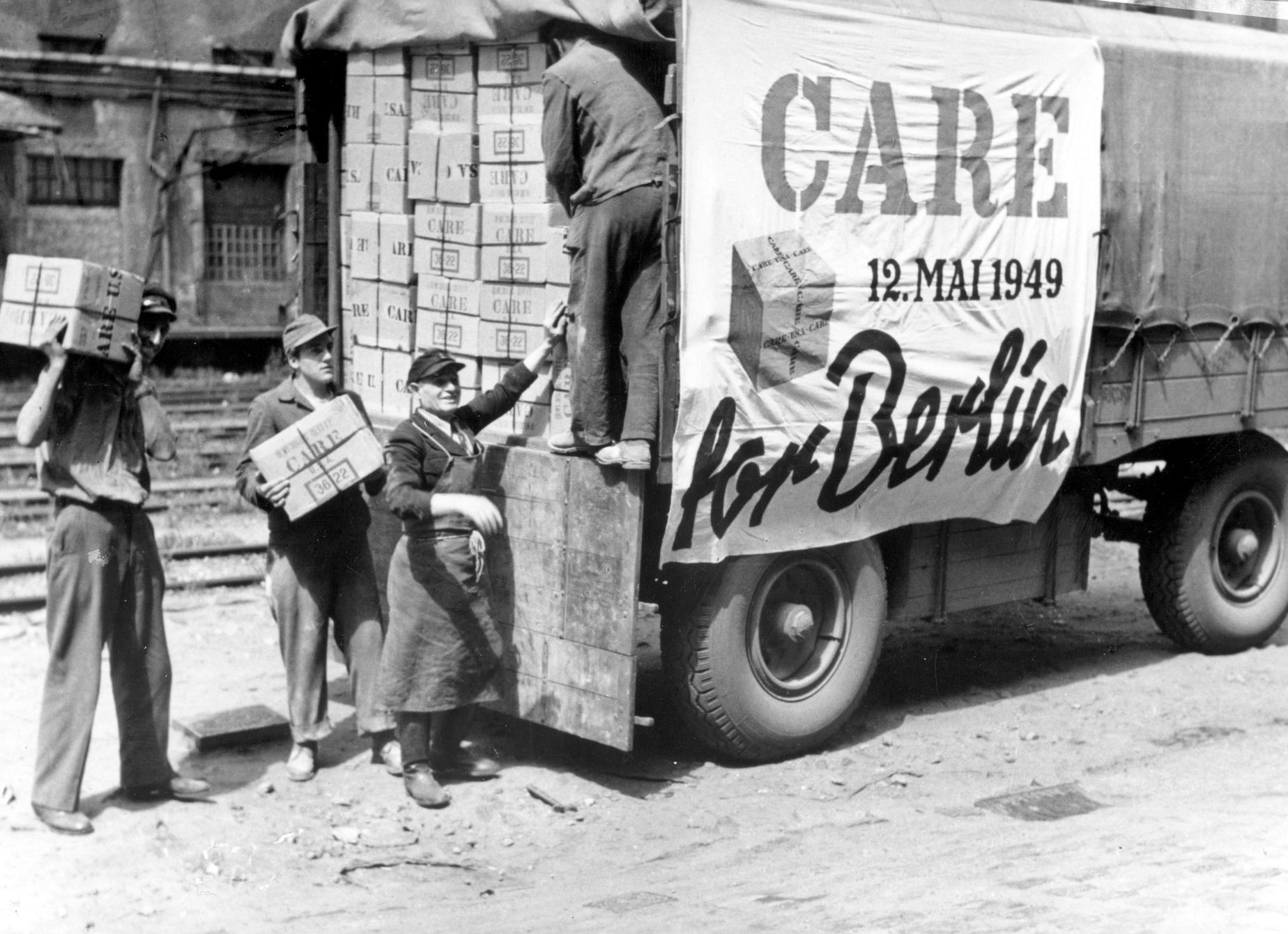

The Soviets eventually backed down and the Russian news outlets started reporting the Soviet’s willingness to end the blockade. Serious negotiations began between East and West, and on May 4, an agreement was made.

The Berlin blockade was lifted on 12 May 1949, one minute after midnight. Immediately, a British convoy set for Berlin, arriving at 5:32AM to a cheering crowd.

Cargo planes kept flying into Berlin until the end of July, after ample supplies were amassed. In total, over 2.3 million tons of food and supplies - including 23 tons of candy - were airlifted over almost 300 000 flights, all in less than a year.

In Tempelhof, the green square near the entrance of the airport was renamed Platz der Luftbrücke, and a monument was erected in honour the valiant aircrews who made this operation possible. Tempelhof was closed in 2008, and the airfield was turned into a park. The Tegel airfield was developed into an airport which remains open to this day.

Gail Halvorsen returned to Utah, where he met the mother of his five children. He flew several humanitarian missions, and returns to Berlin every year to drop candy in commemoration of the airlift.