Pratt & Whitney internal tools

Built in

During my internship at Pratt & Whitney, I found myself with a lot of time on my hands. I was hired to maintain a simple web application, but my work was done after a week or two. With 3 months left to the internship, I found something else to do.

Cleaning up the code

That web application had been left in a sorry state. Despite storing classified military data, it was riddled with security issues. Its creator didn’t know about SQL injection. A thorough cleanup of the codebase didn’t only solve those problems. It also reduced its size by over 60%. Never has a code refactor been so thoroughly satisfying.

Automating the process

While refactoring the code, I became more familiar with the application and its purpose within the department.

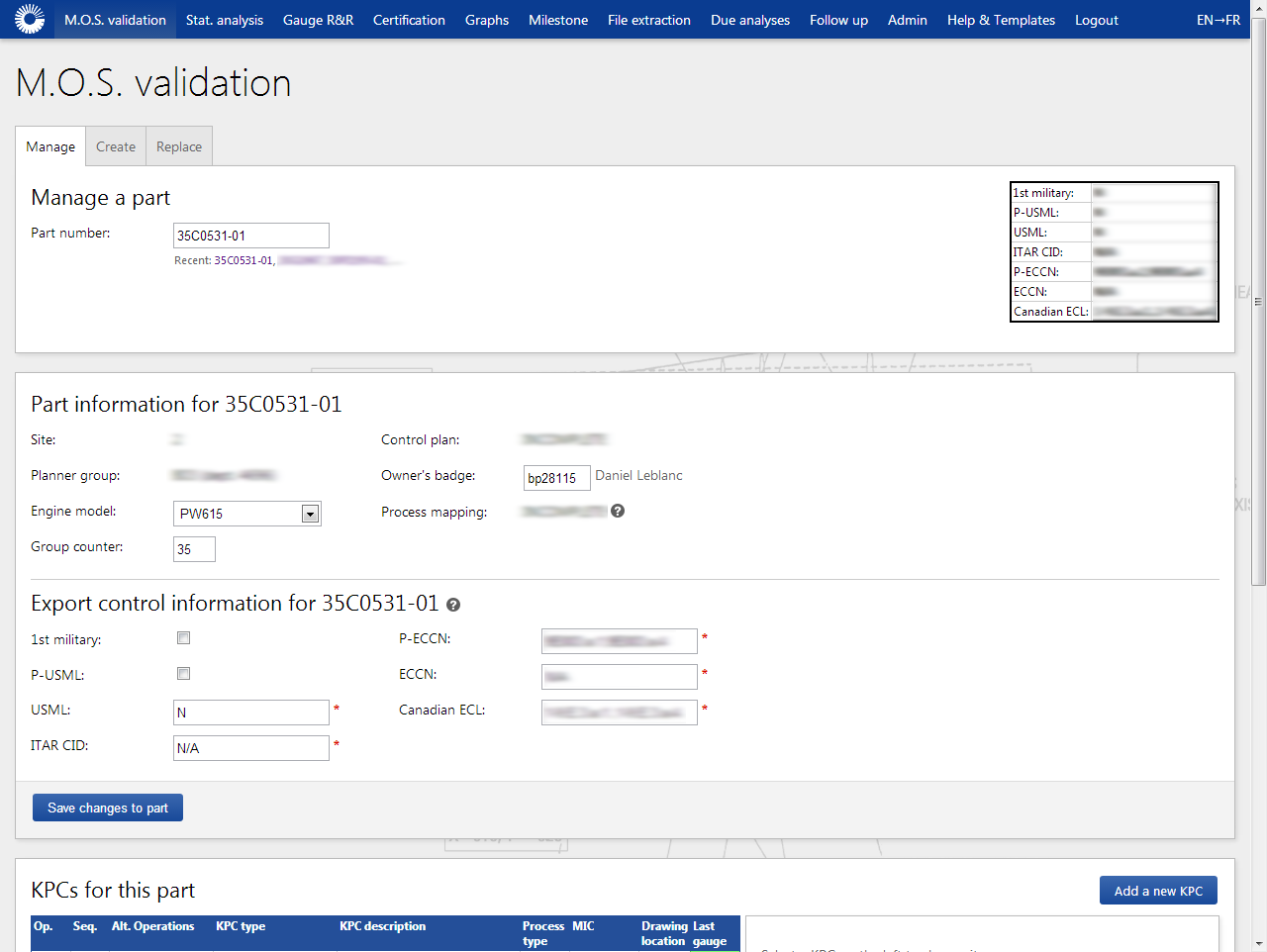

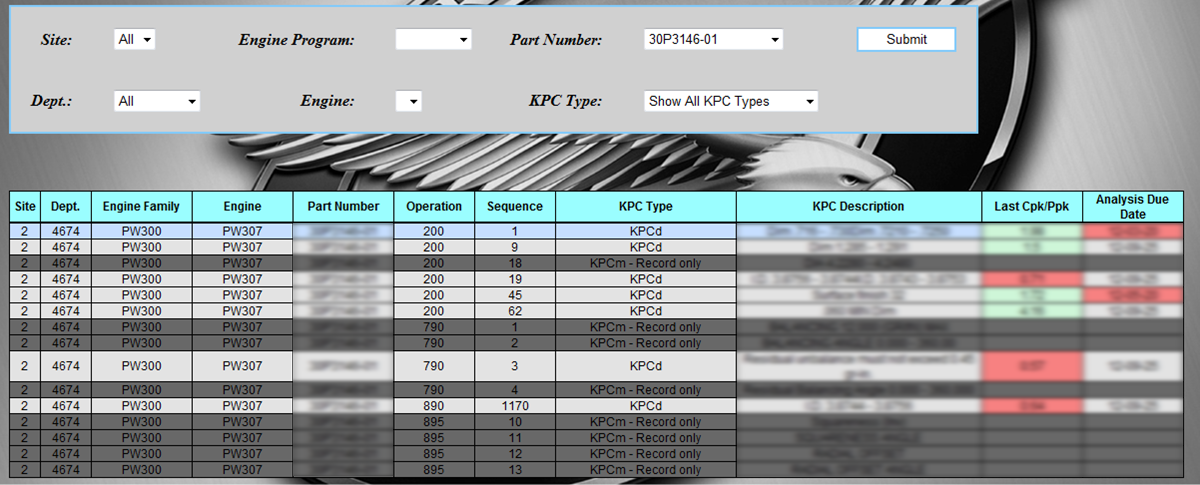

Pratt & Whitney makes airplane parts. Precise work requires precise tools. Every 3-6 months, the tools had to be tested. If the test results were outside of a certain range, the tool had to be recalibrated. Our application listed tools that were due for testing, stored test results, and flagged tools that needed recalibration.

Here’s a summary of how it was done:

- A user exported tool data from an external system, opened it in excel, and filtered out some of the values.

- The user then fed that data to a statistical analysis tool. After some fiddling with the menus, it showed a graph and some values.

- The user put a screenshot of the graph in a PowerPoint template and saved a copy somewhere. Nobody knew why. It just had to be done.

- The user entered the values from the statistical analysis tool in the web application, which saved them in a database.

- Repeat a few hundred times per week.

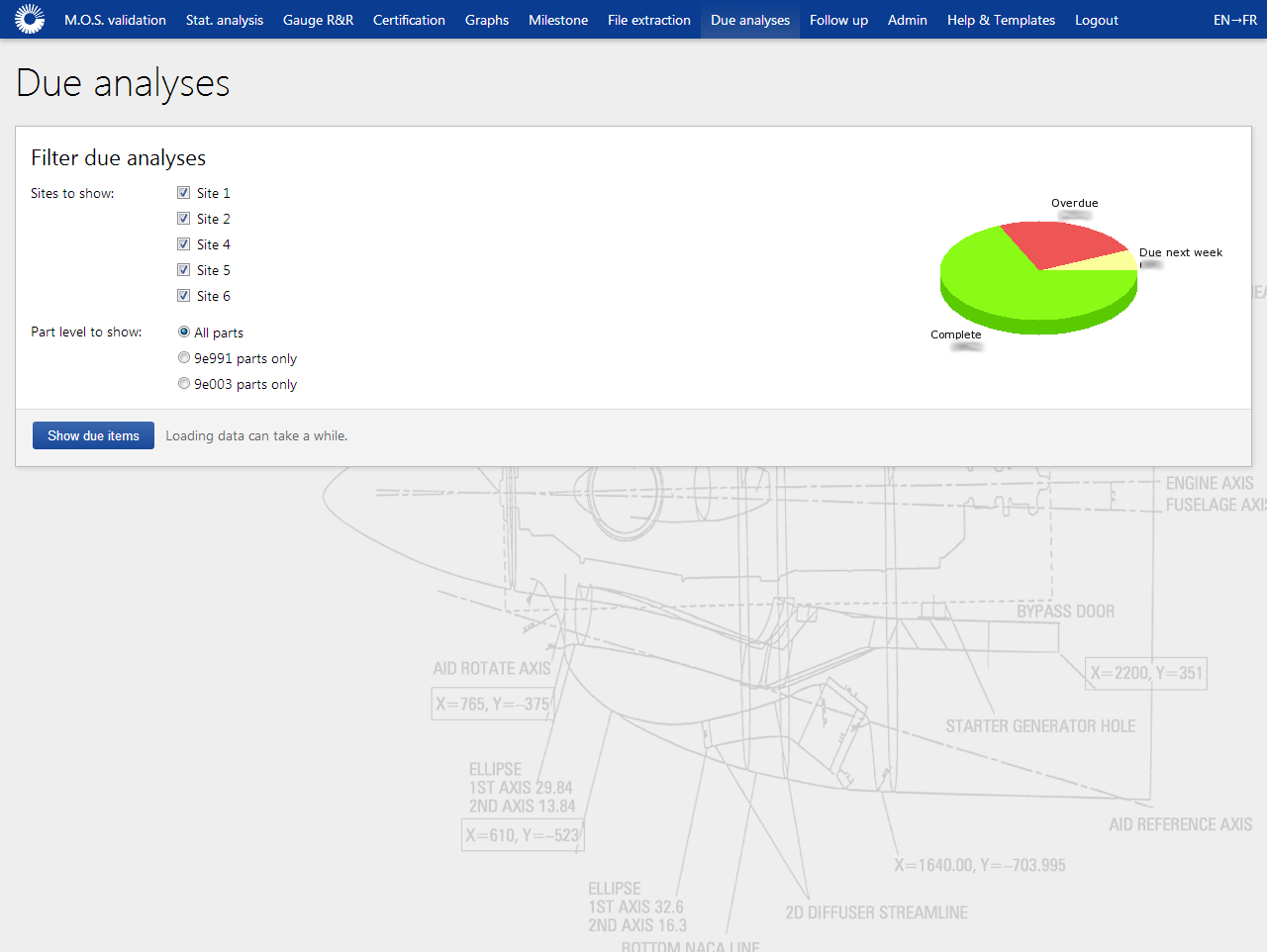

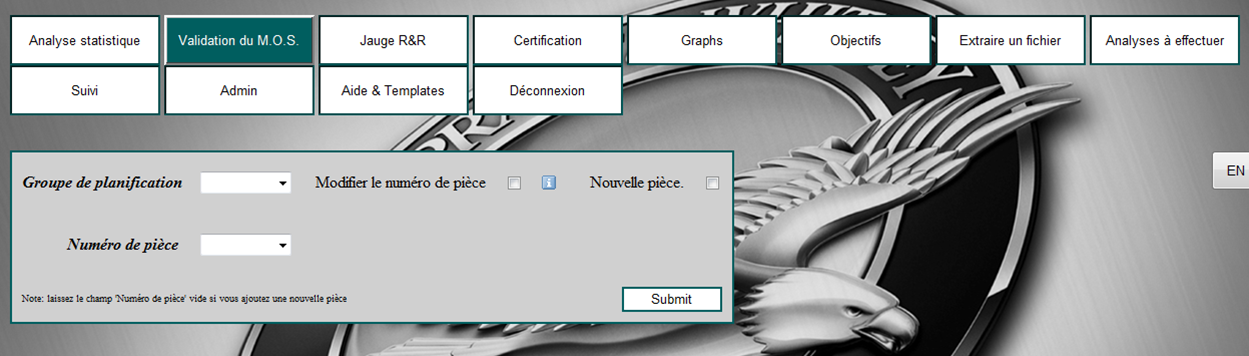

- A manager could then look at those values, and list those that were flagged for recalibration.

This was a tedious data entry job. Each tool took roughly 10 minutes to process. Most of the work was done by a full time employee in India, but some parts contained sensitive military information. They had to be processed by an intern with the right clearance: me.

I quickly realised that I’d be doing this for roughly 5 hours a week. It was unbearably boring, but also very error-prone. Shuffling data around and pasting it in different places can easily cause data entry errors.

After asking around, I learned that this application was an exact copy of the paper forms it replaced. No one had considered that the new medium offered new possibilities. Automation, for instance.

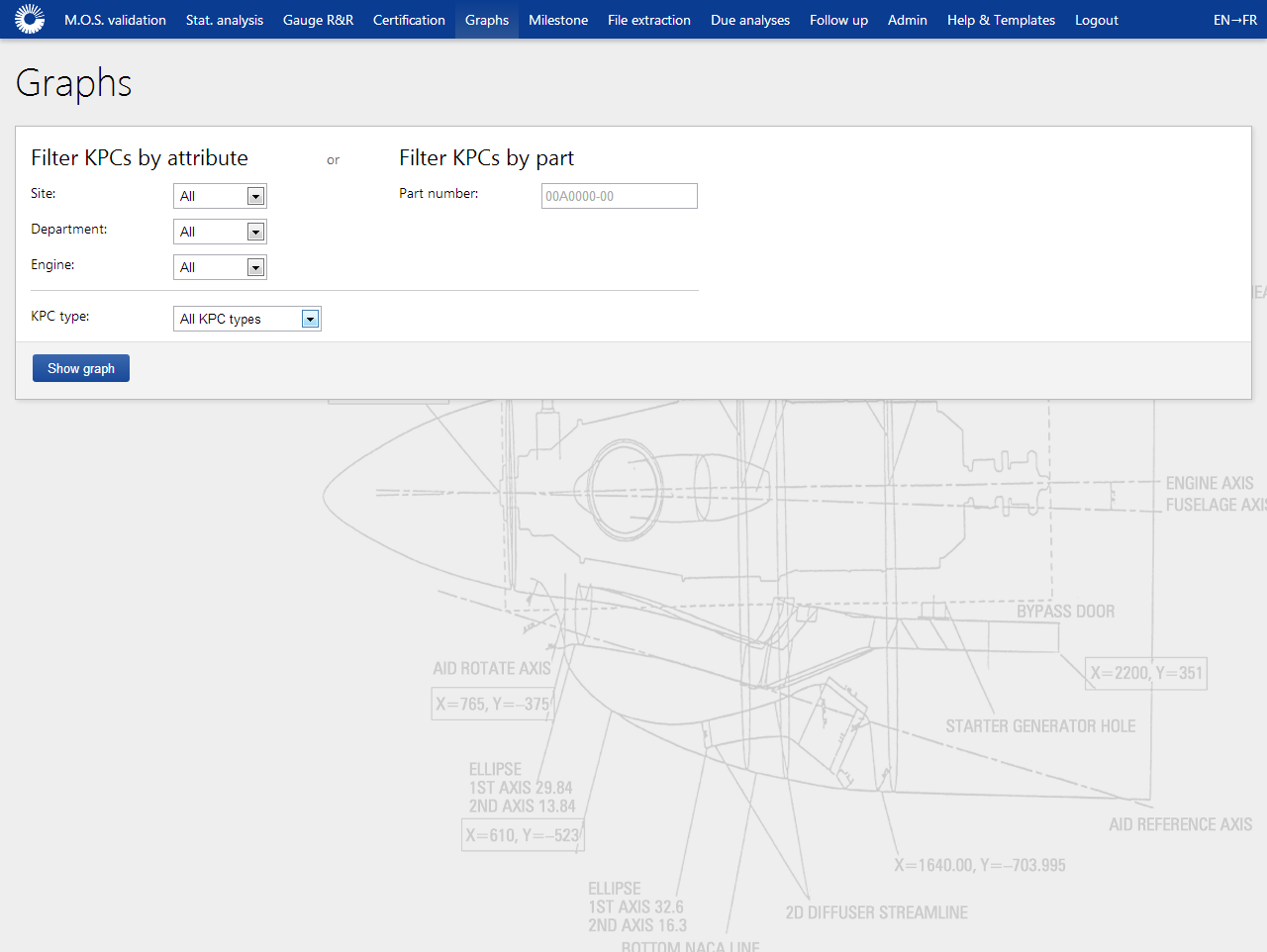

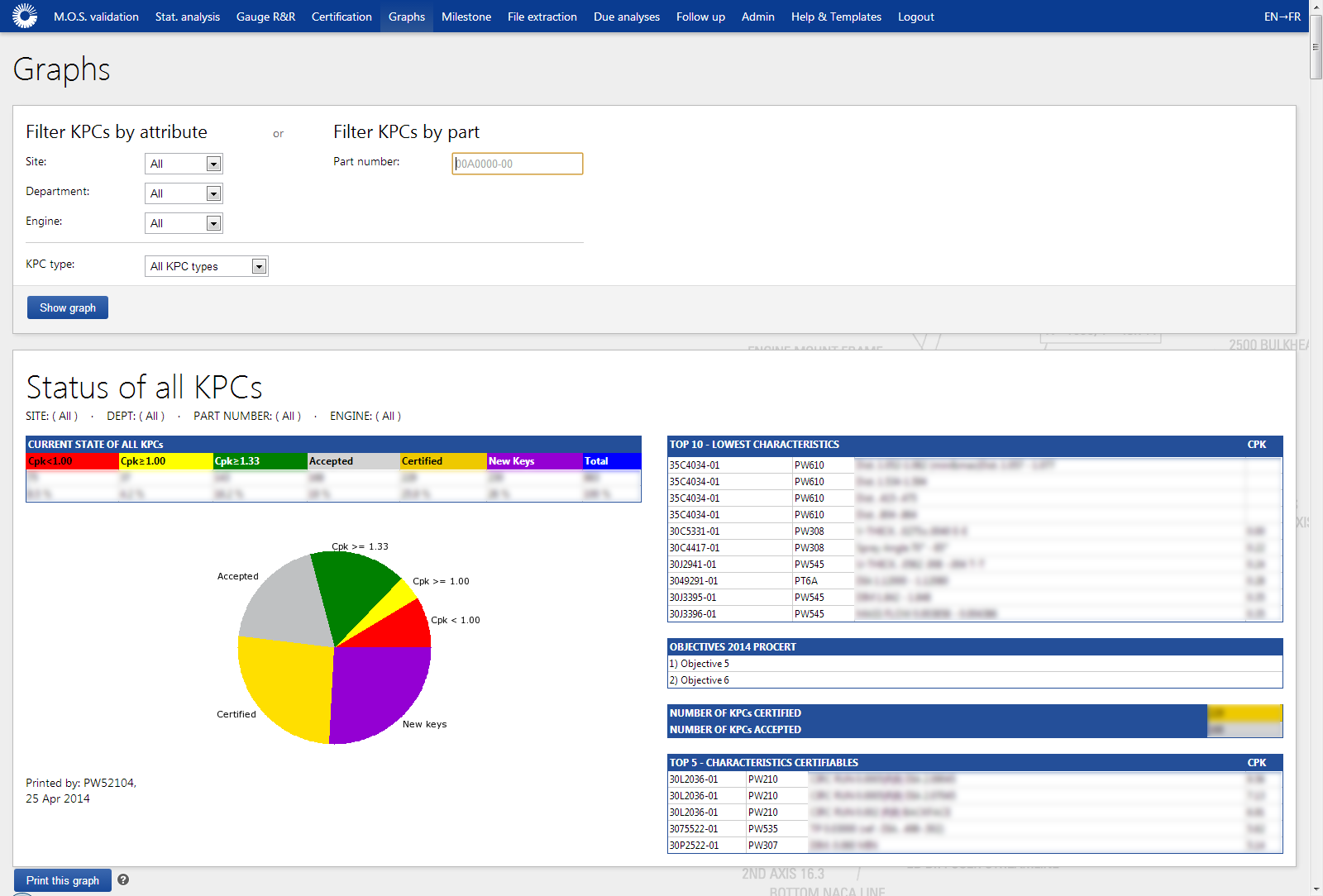

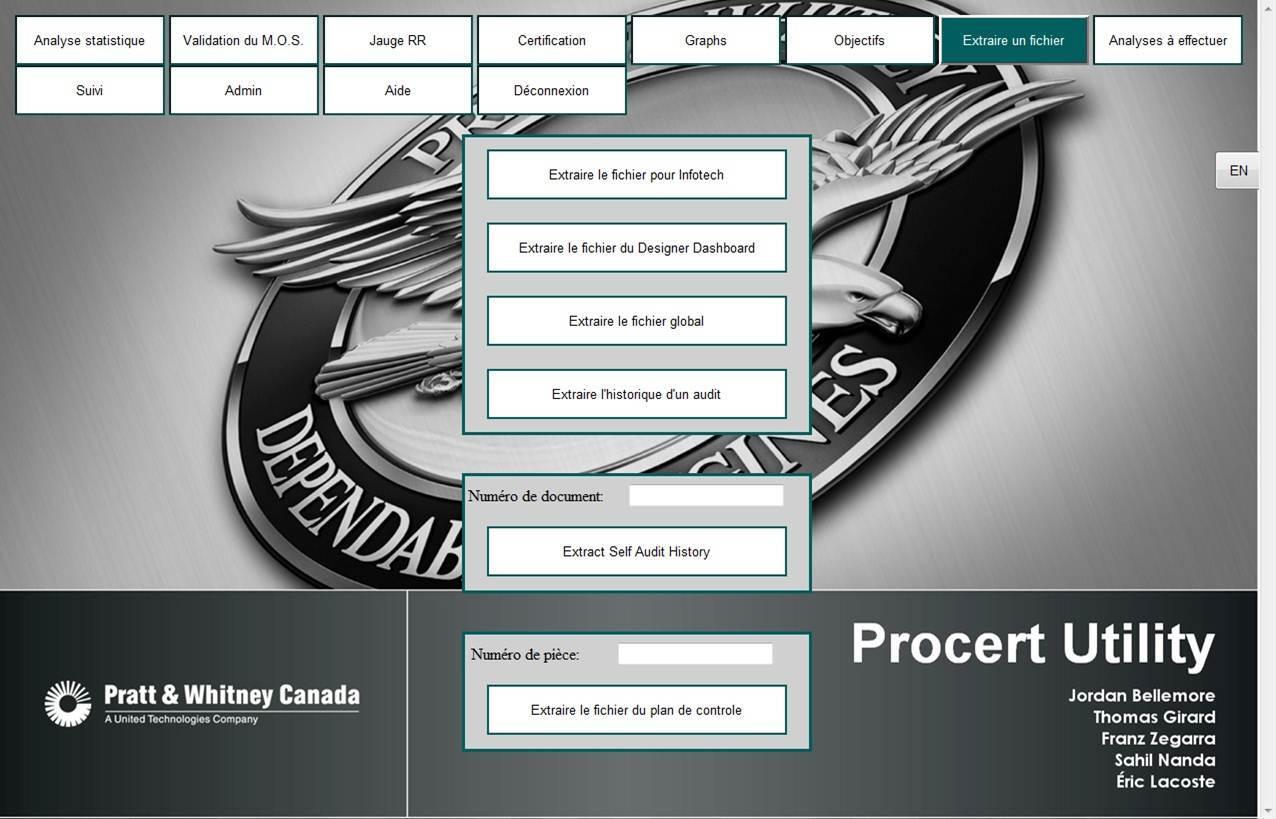

Over a few weeks, I reduced the process to a few keypresses. It now looked like this:

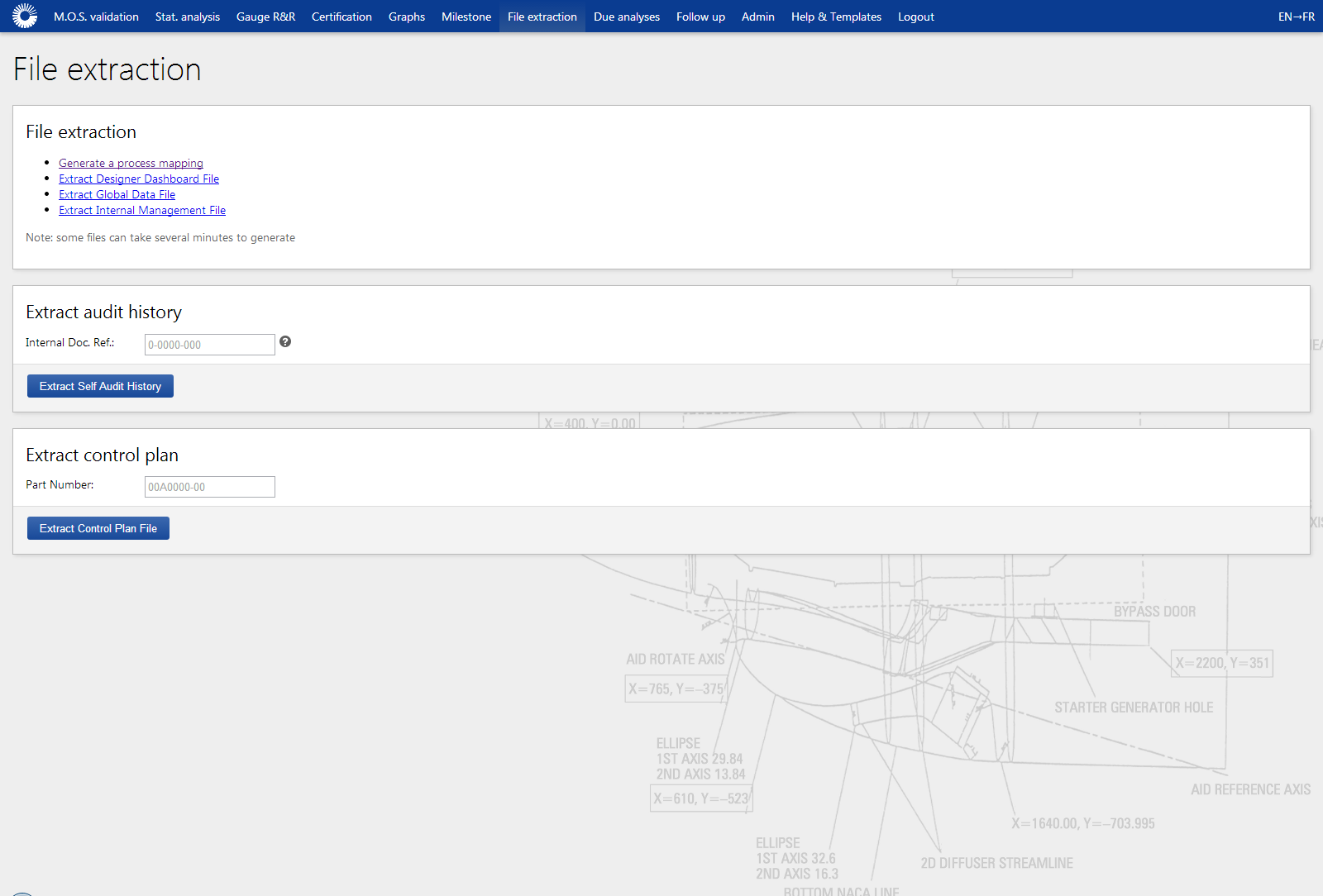

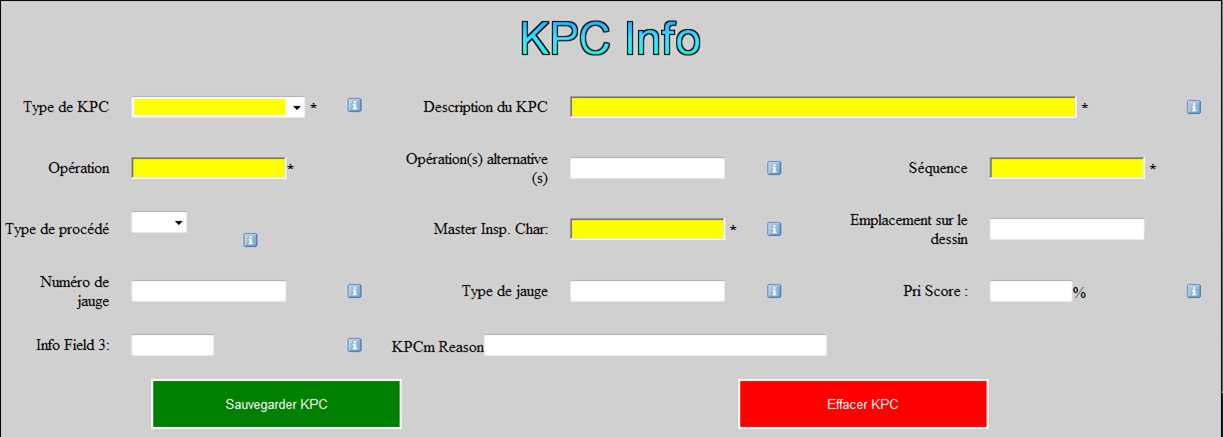

- User enters a part number.

- The application fetches the data from the external system, transforms it, performs statistical analysis on it, generates and saves a graph, saves the results, and shows the values to the user.

- The user approves the results.

- A manager can then look at those values, and list those that were flagged for recalibration.

Instead of spending 10 minutes per part, I now spent 15 seconds.

In reality, no human intervention was necessary. The data from the automated process wasn’t tainted by the possibility of human error. If any error was found in the application’s code, it could be fixed, and the last few years of test data could be reprocessed in an hour. Unfortunately, I couldn’t get this approved before the end of my internship.

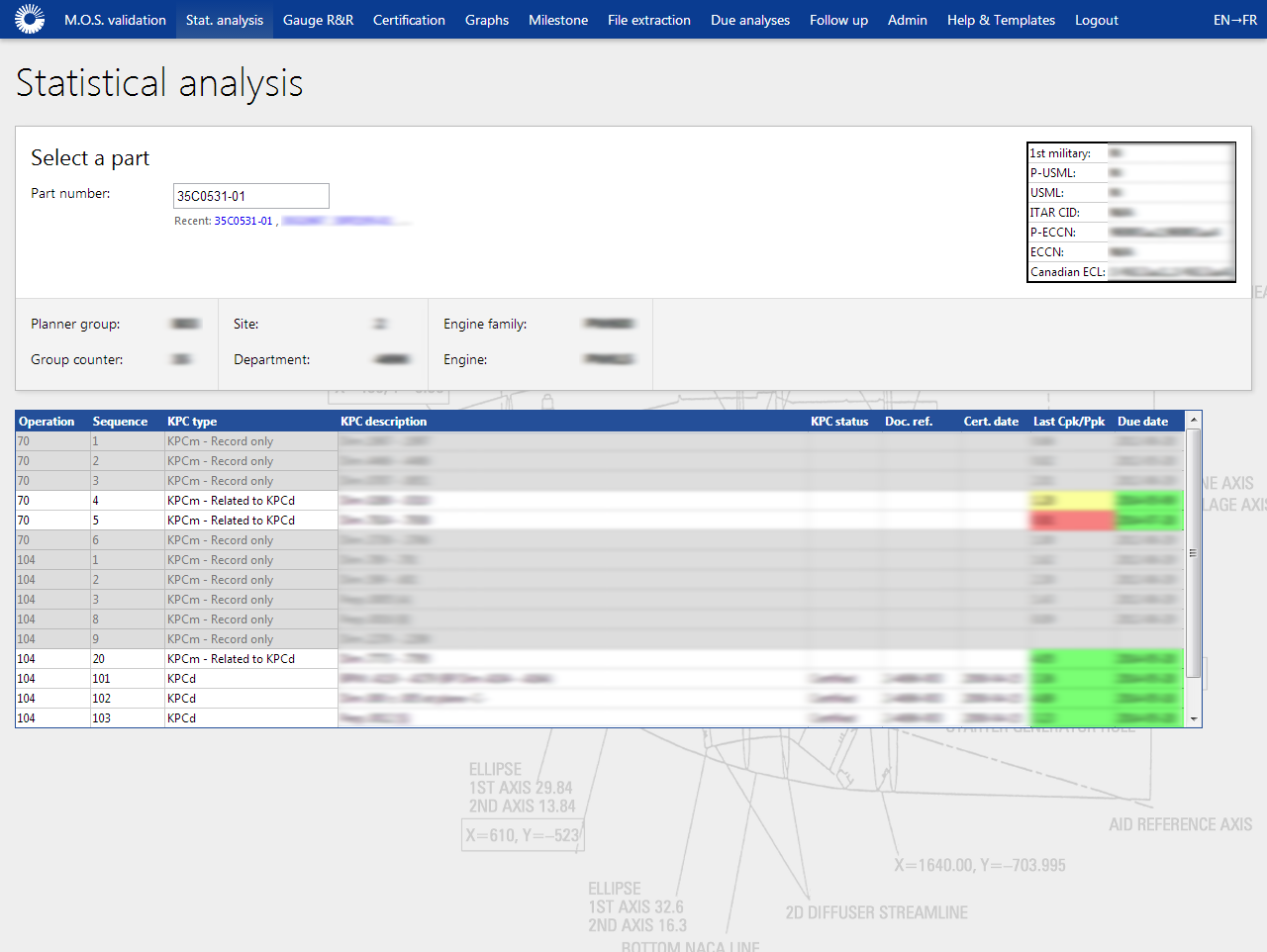

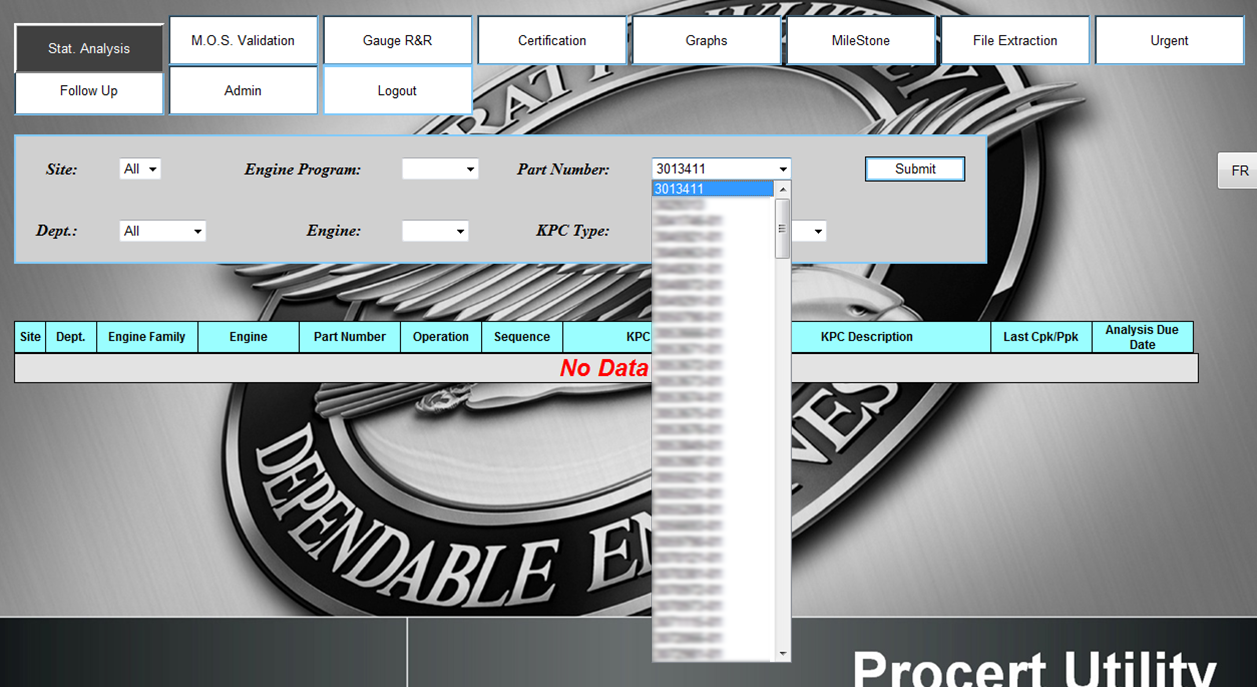

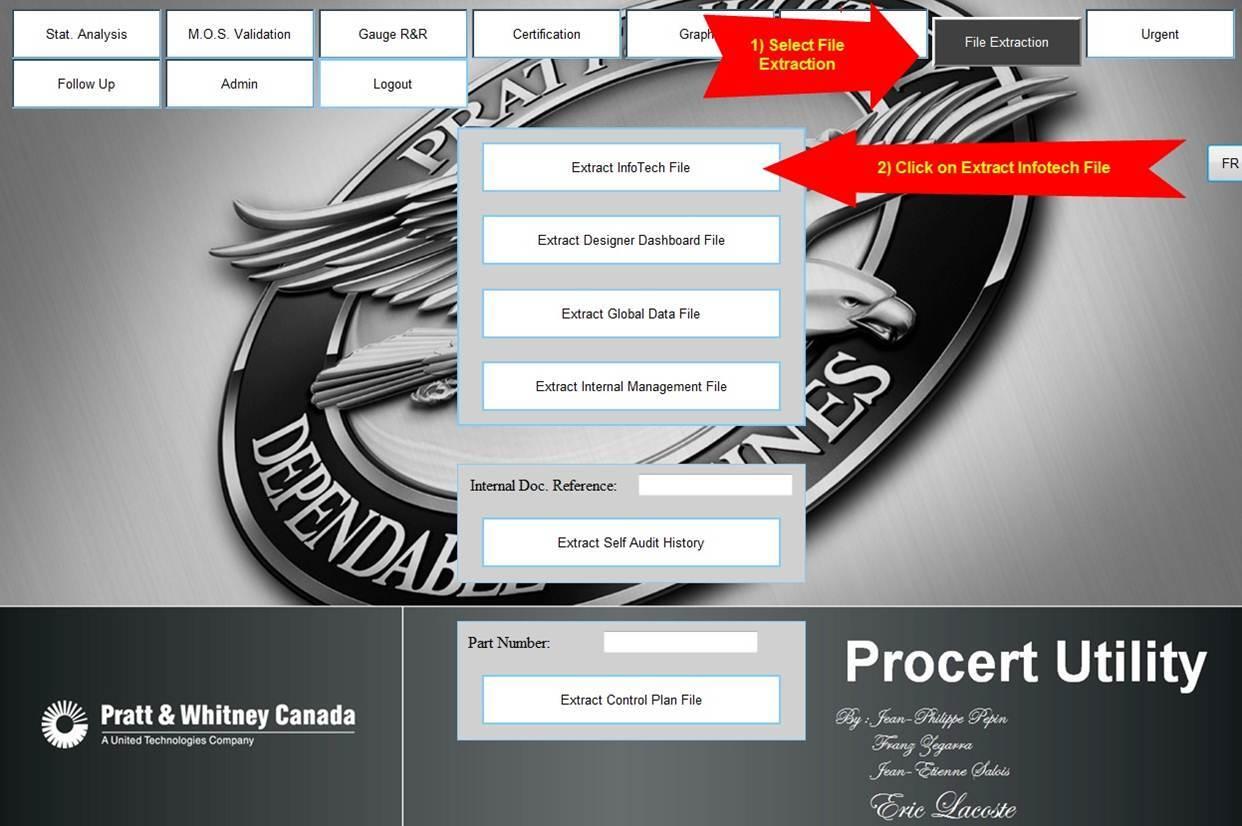

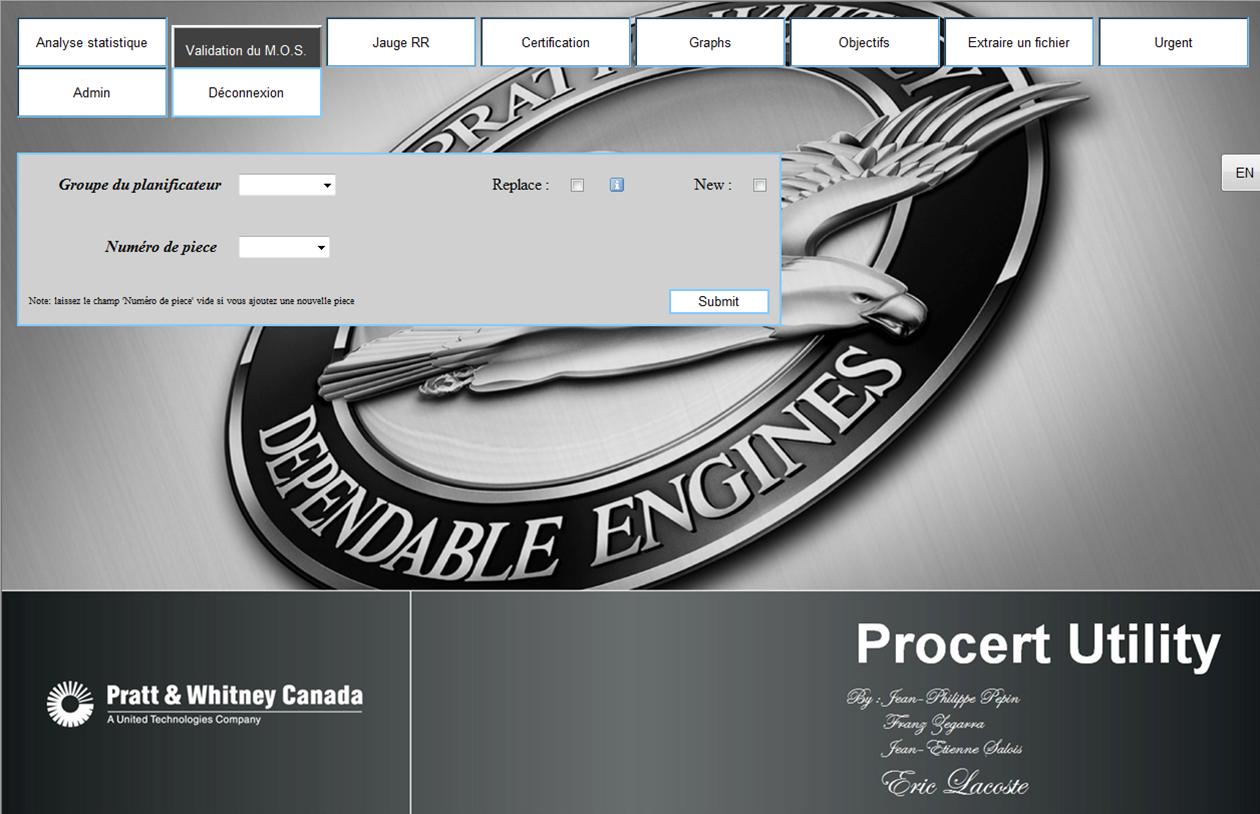

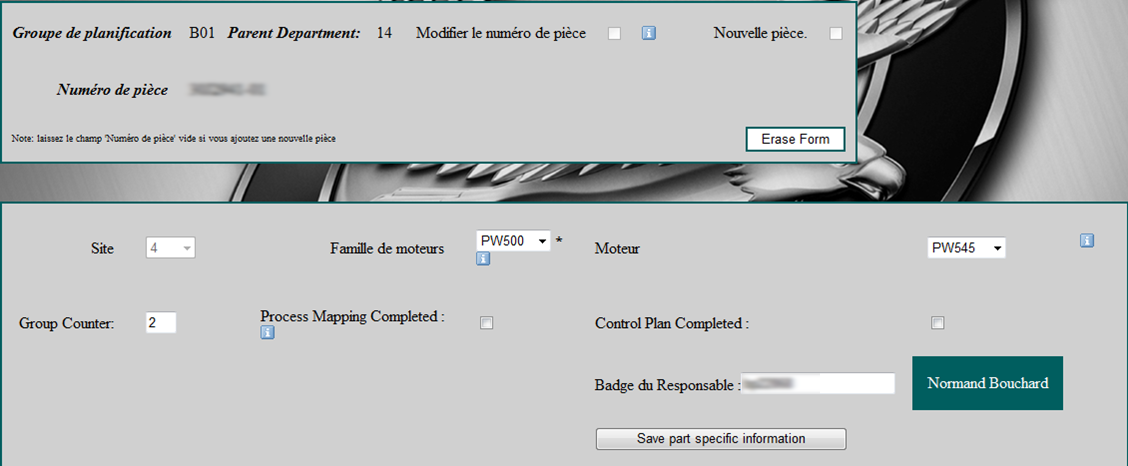

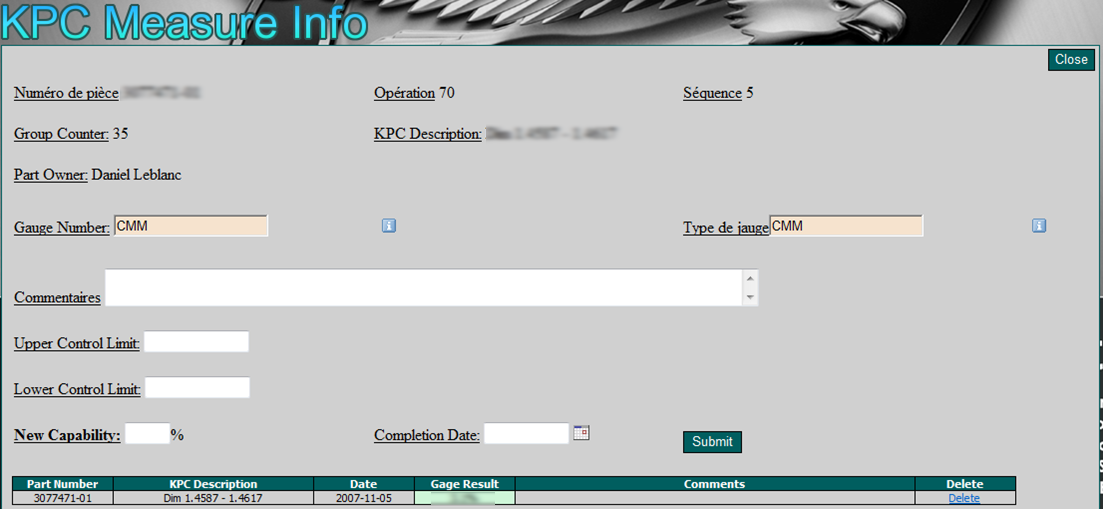

Before

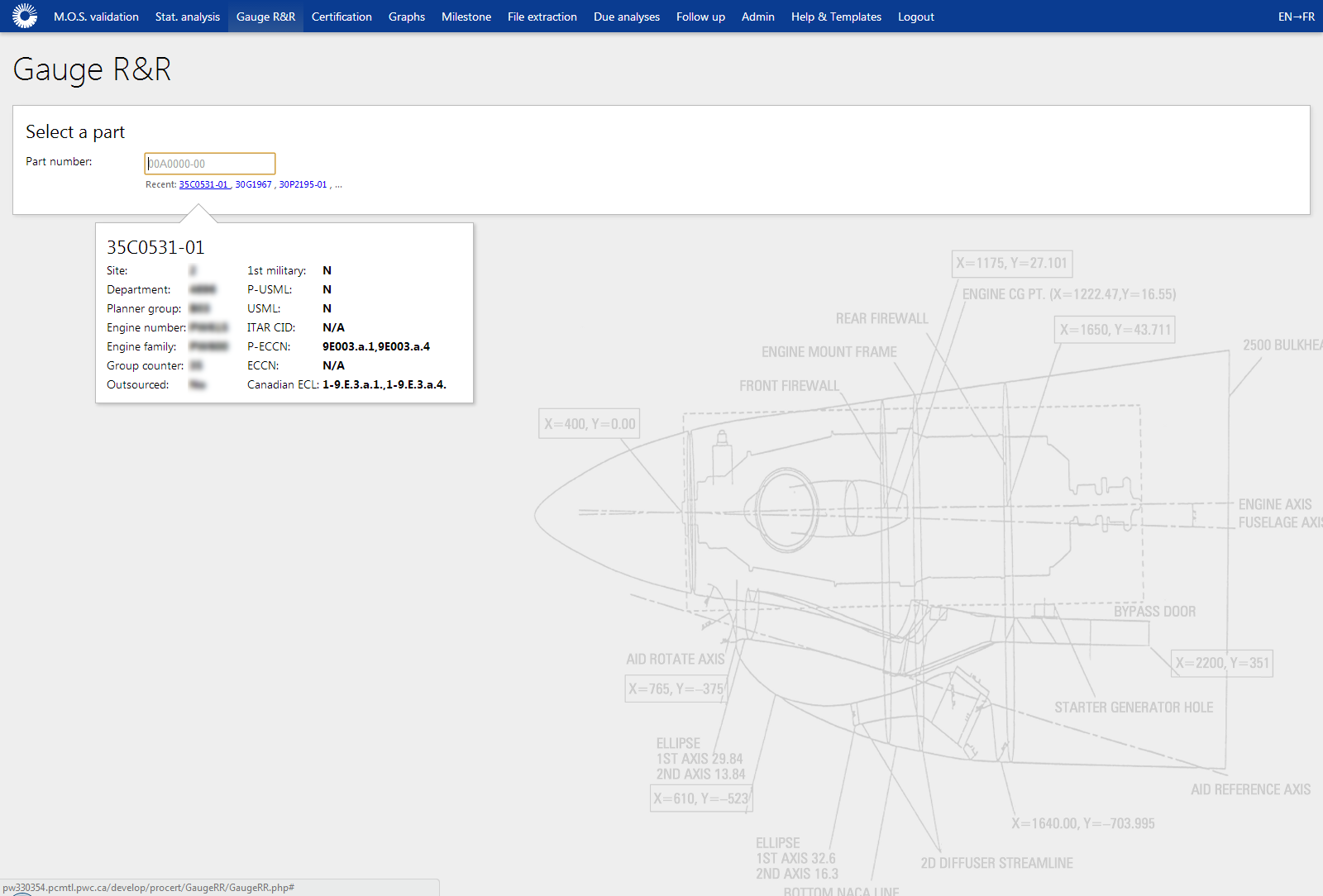

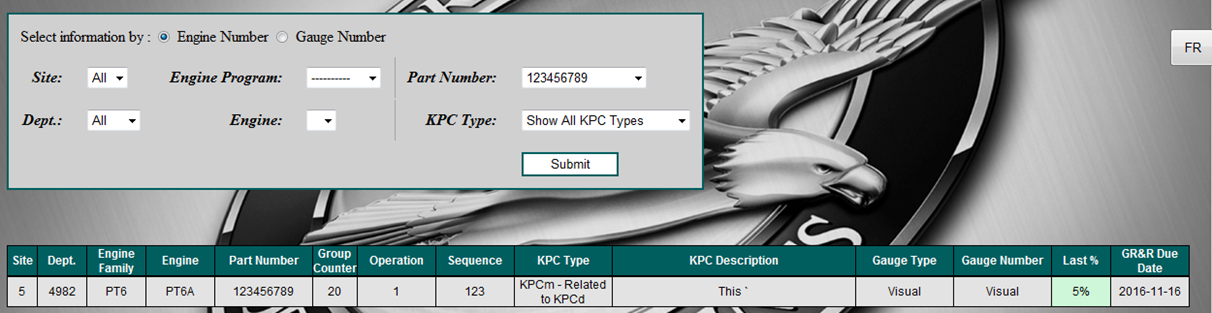

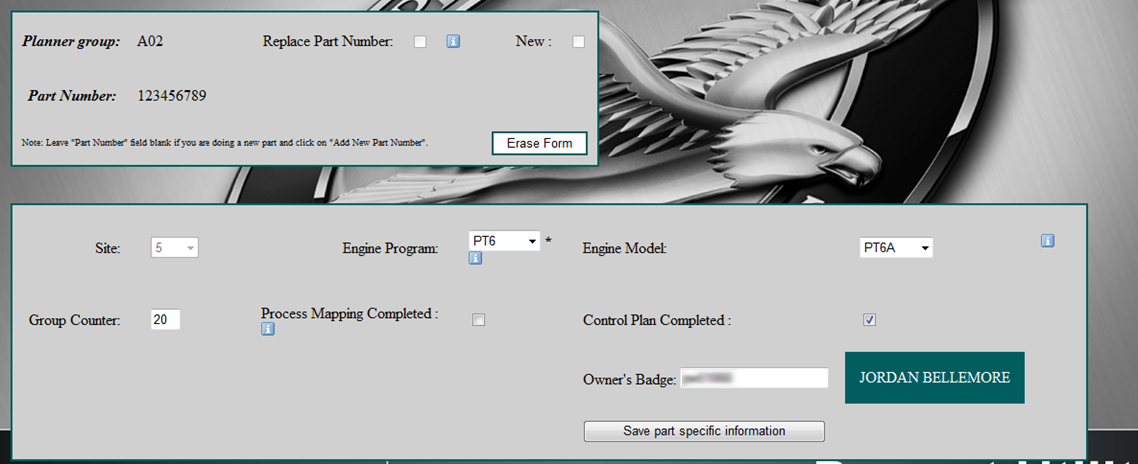

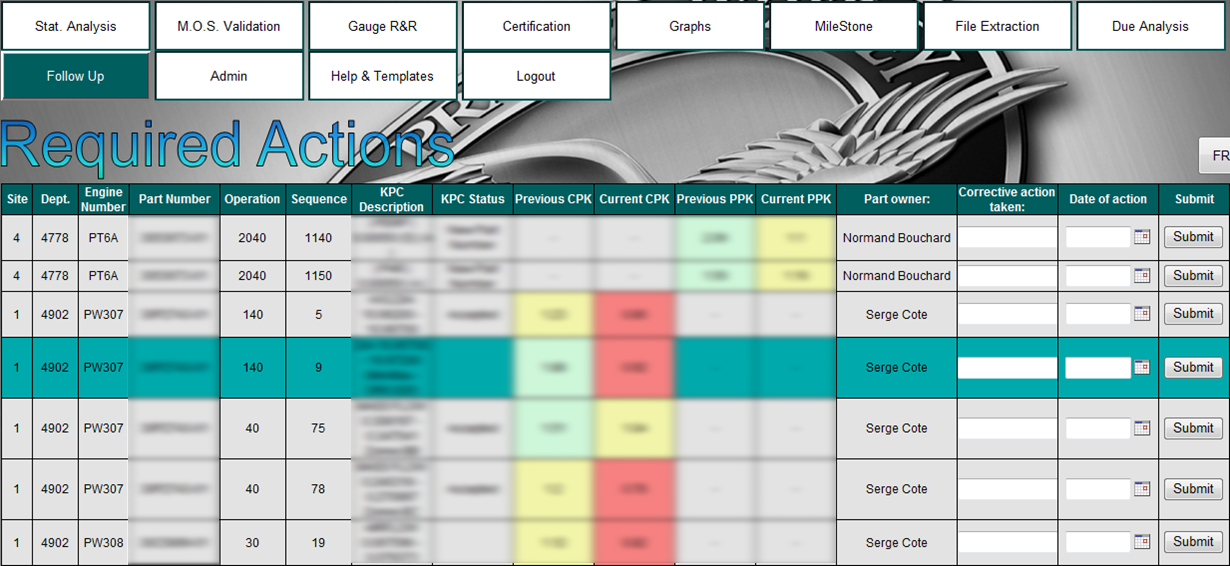

After