Timeline

Built in

There’s a more recent version of this project. You should check it out!

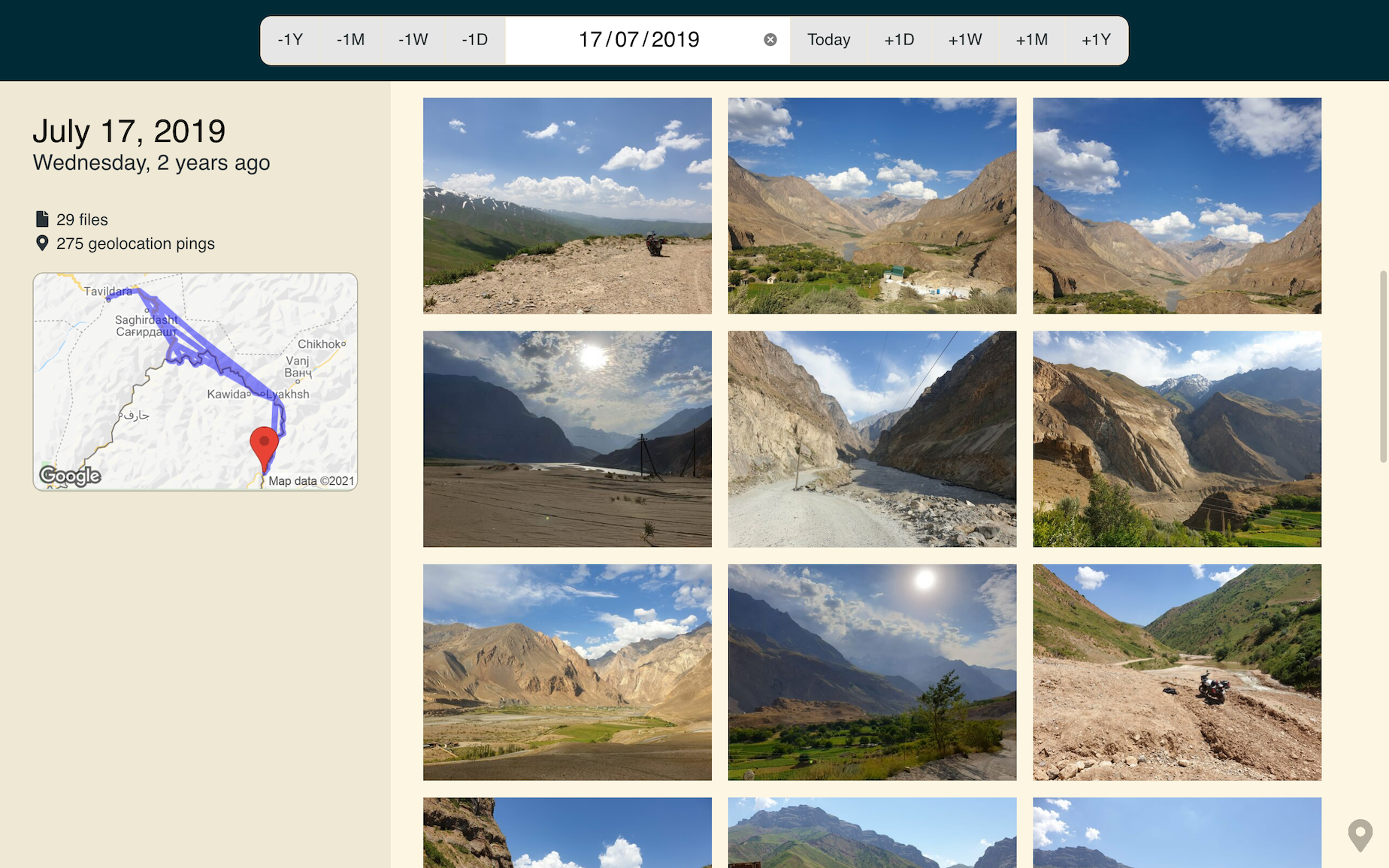

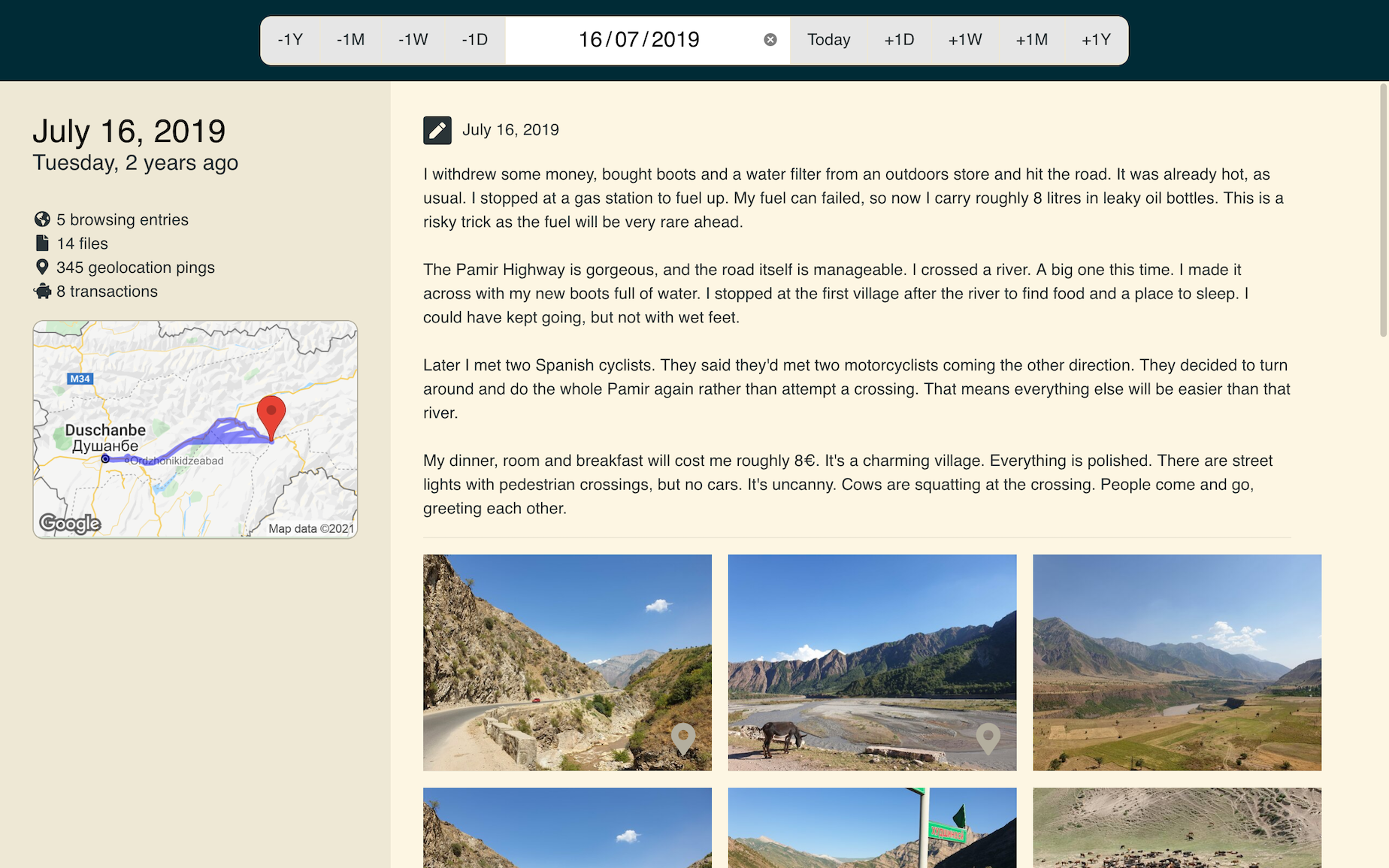

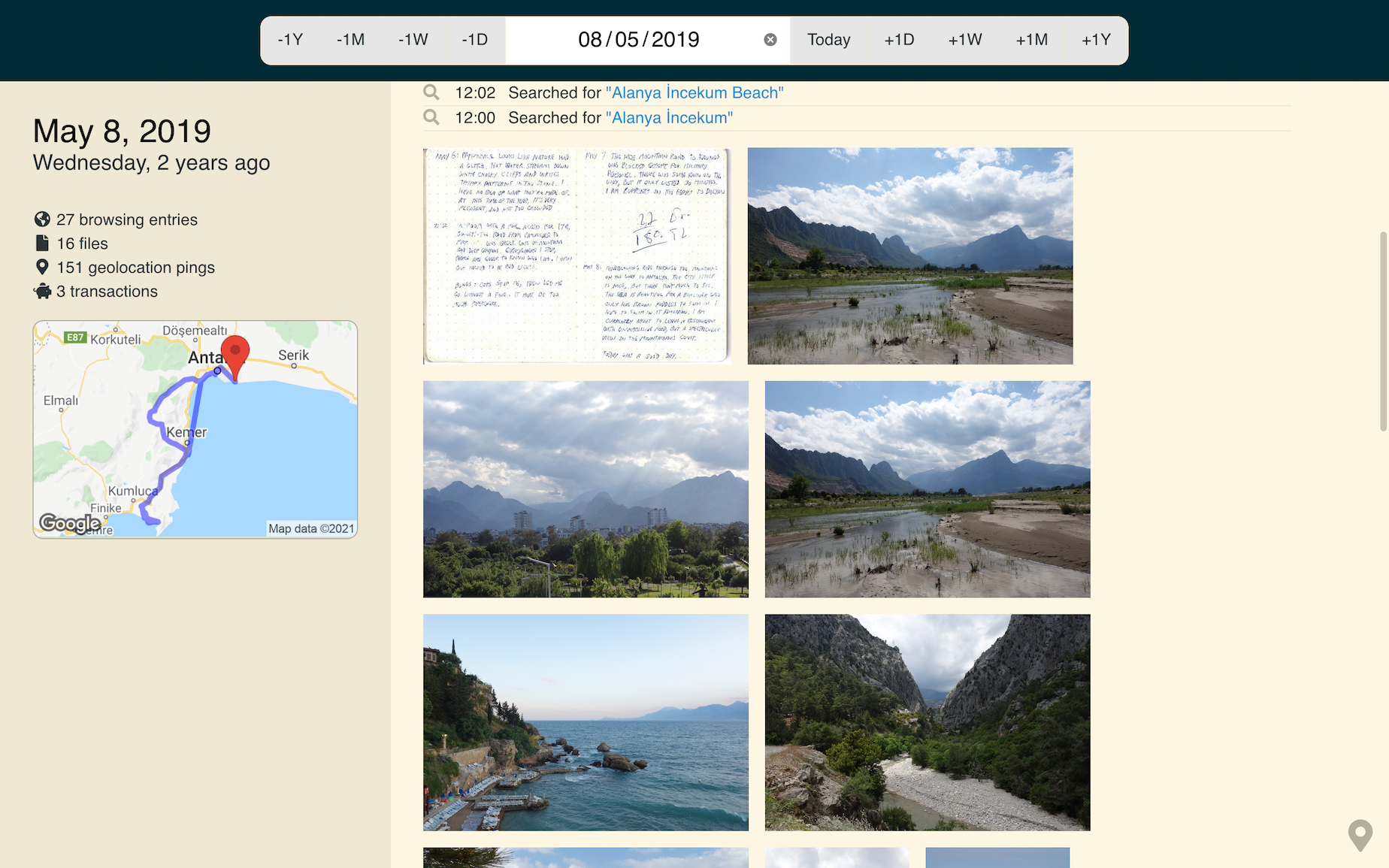

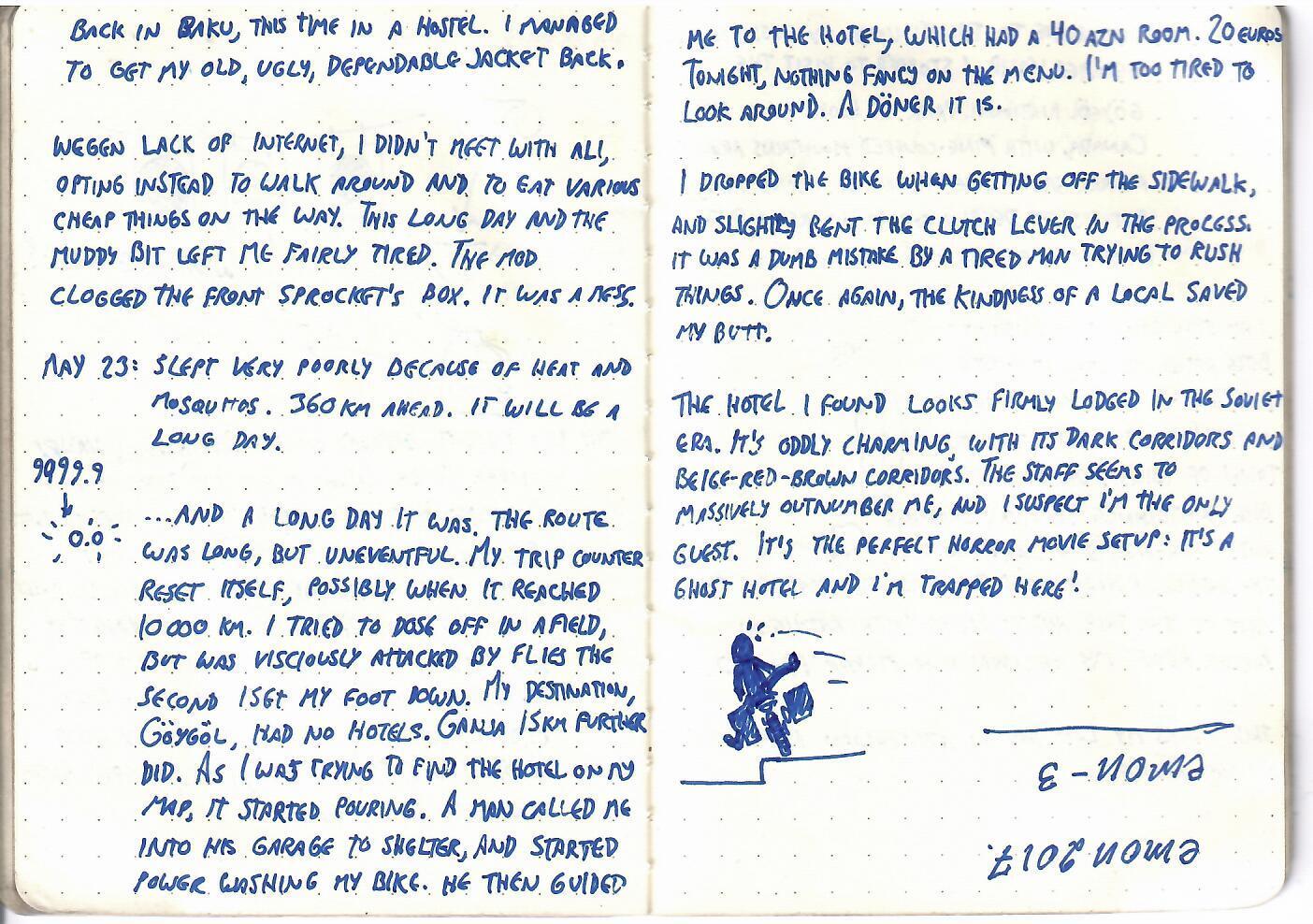

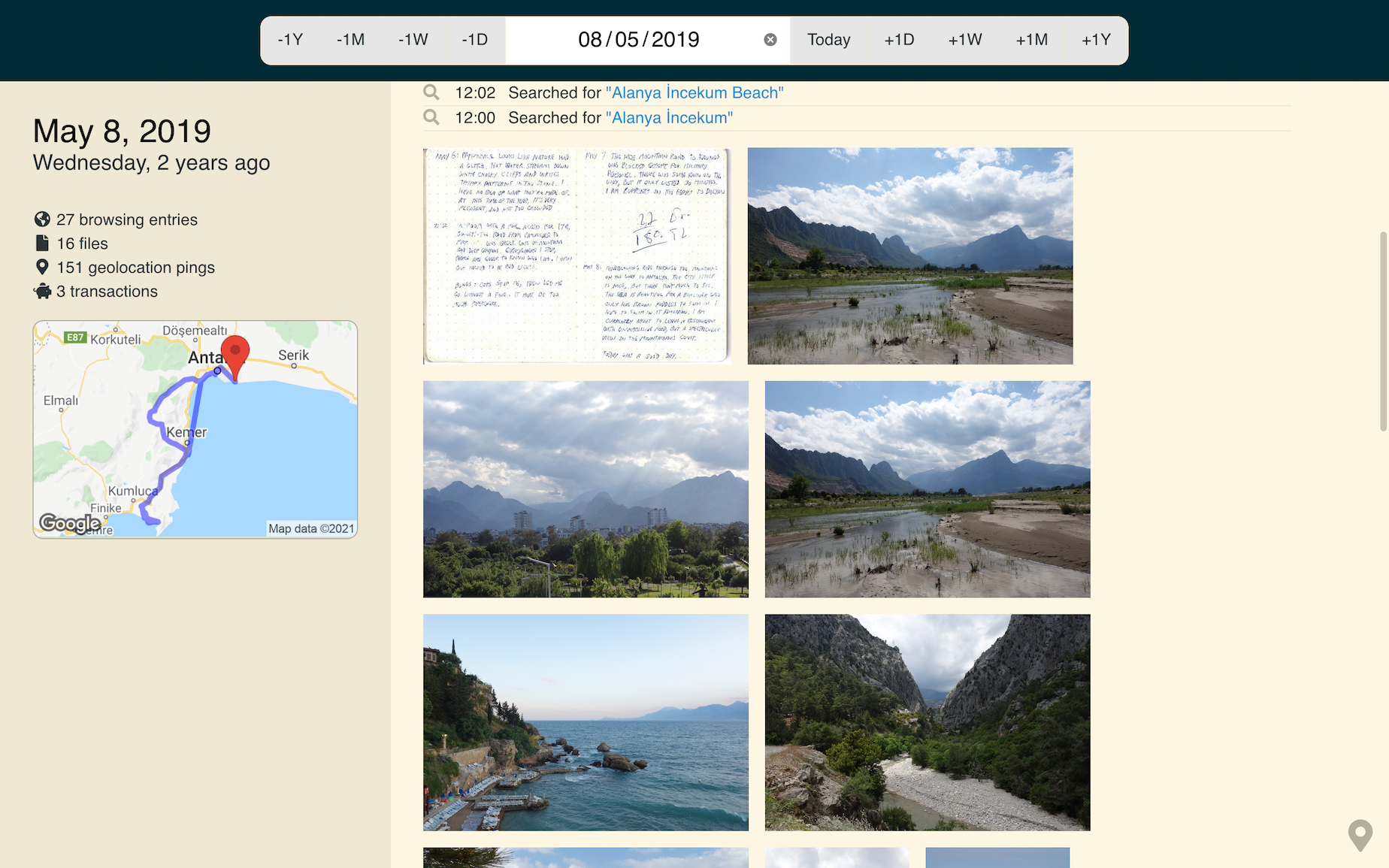

This is a page from my travel journal. It’s from a day in 2019, when I was on my way to Central Asia.

In time, those precious memories will fade, and all that will remain of my journey through Azerbaijan will be a line on a map and a few landscape photos. There would be nothing left of the crunchy bits that bring the story to life.

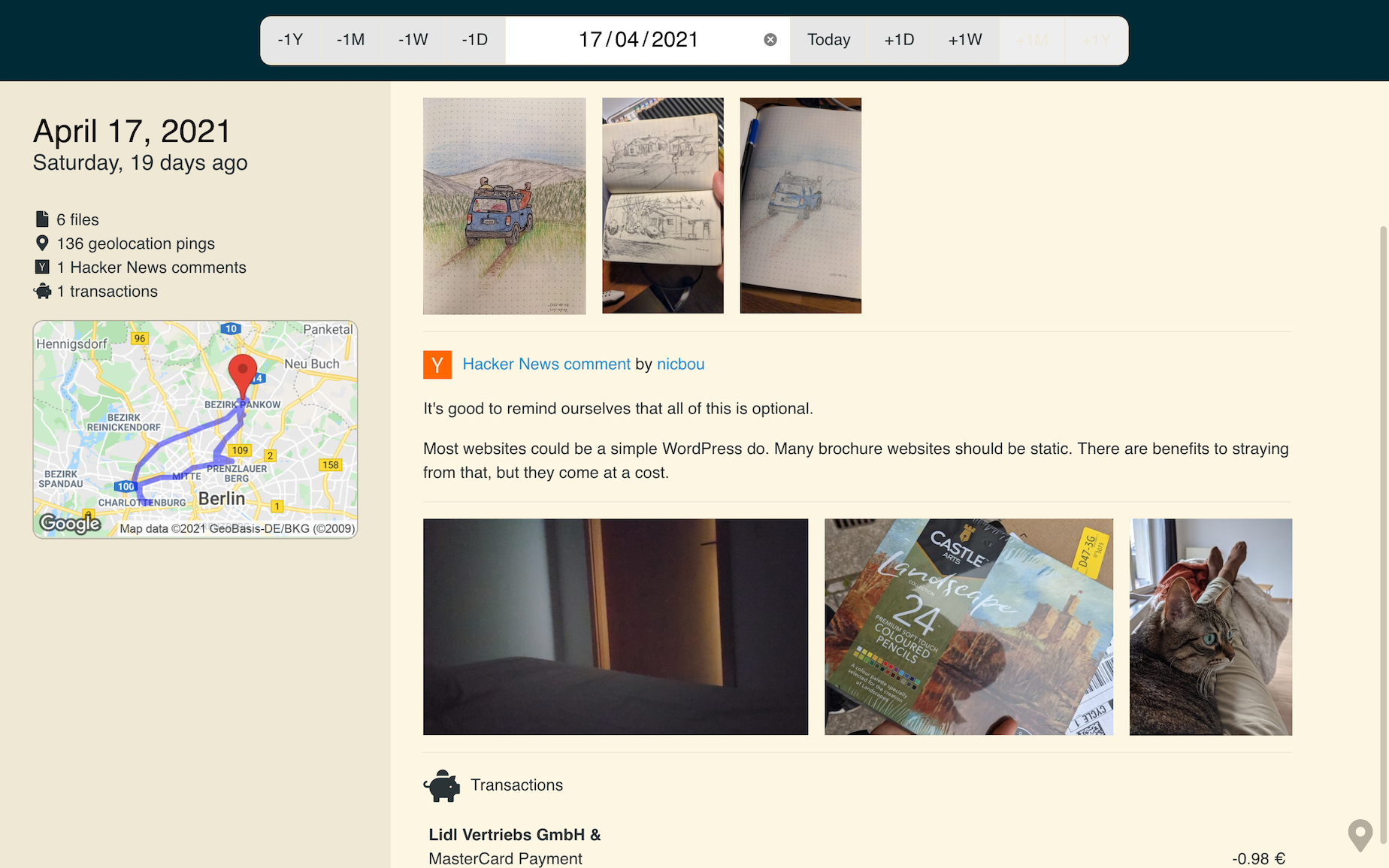

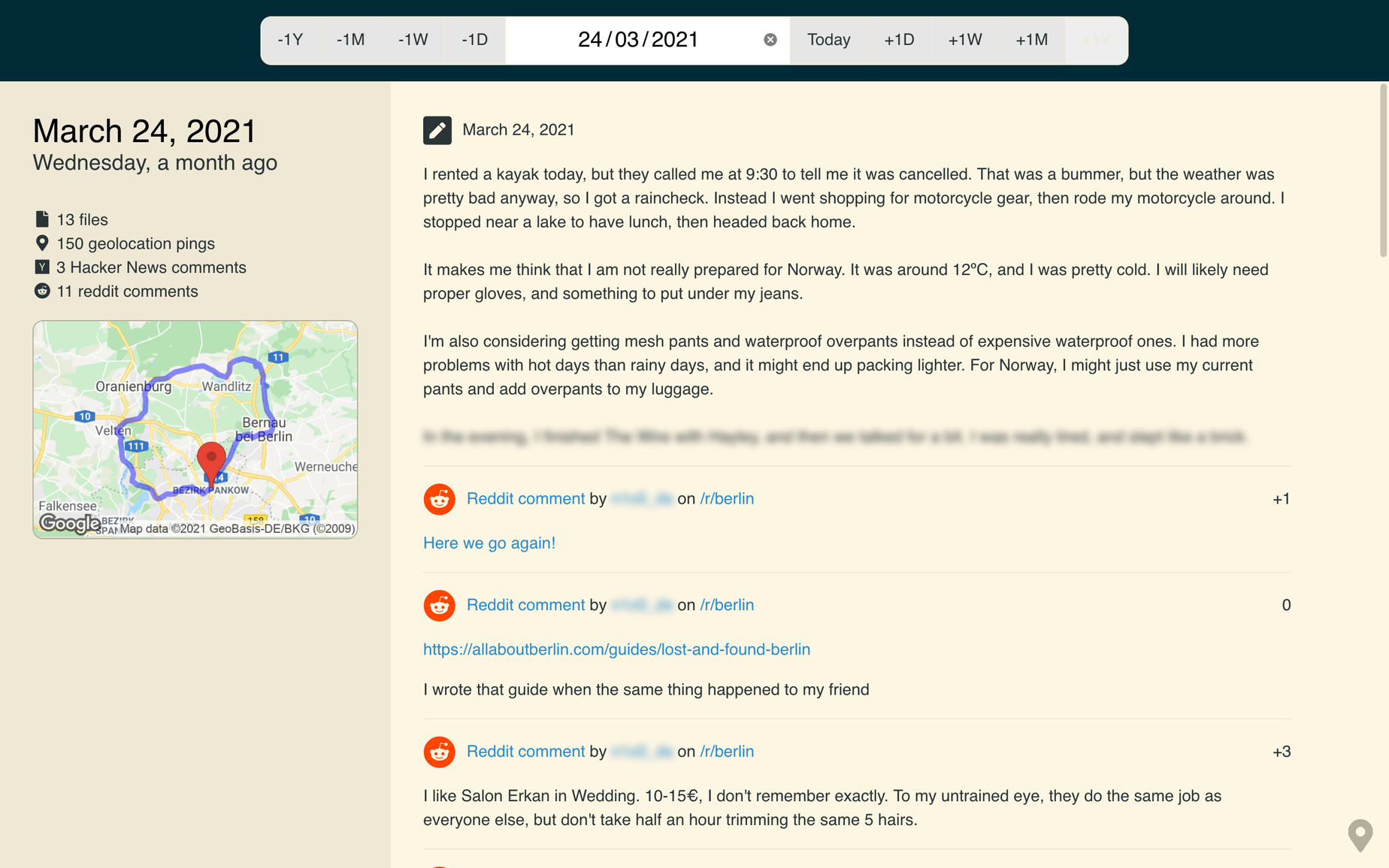

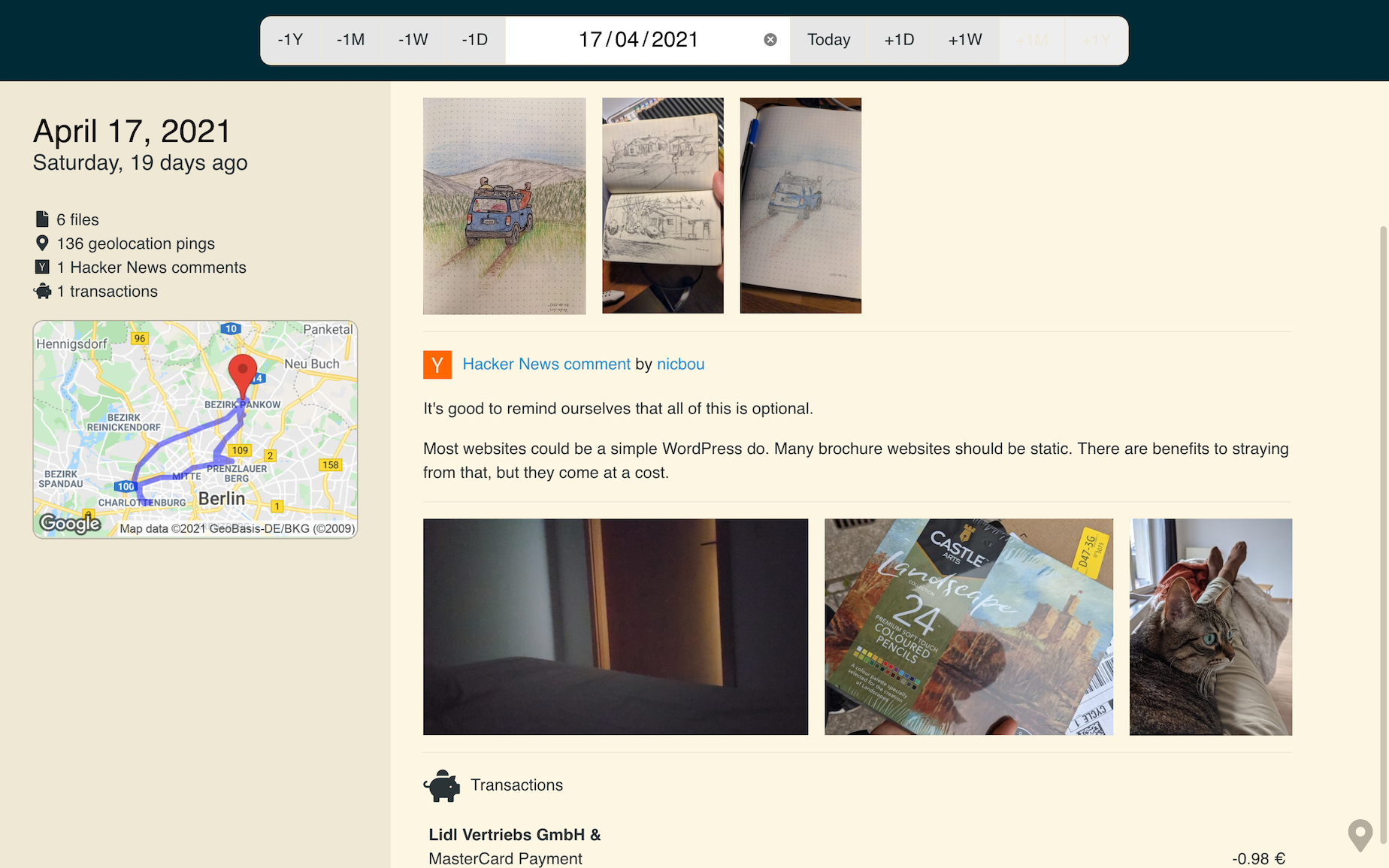

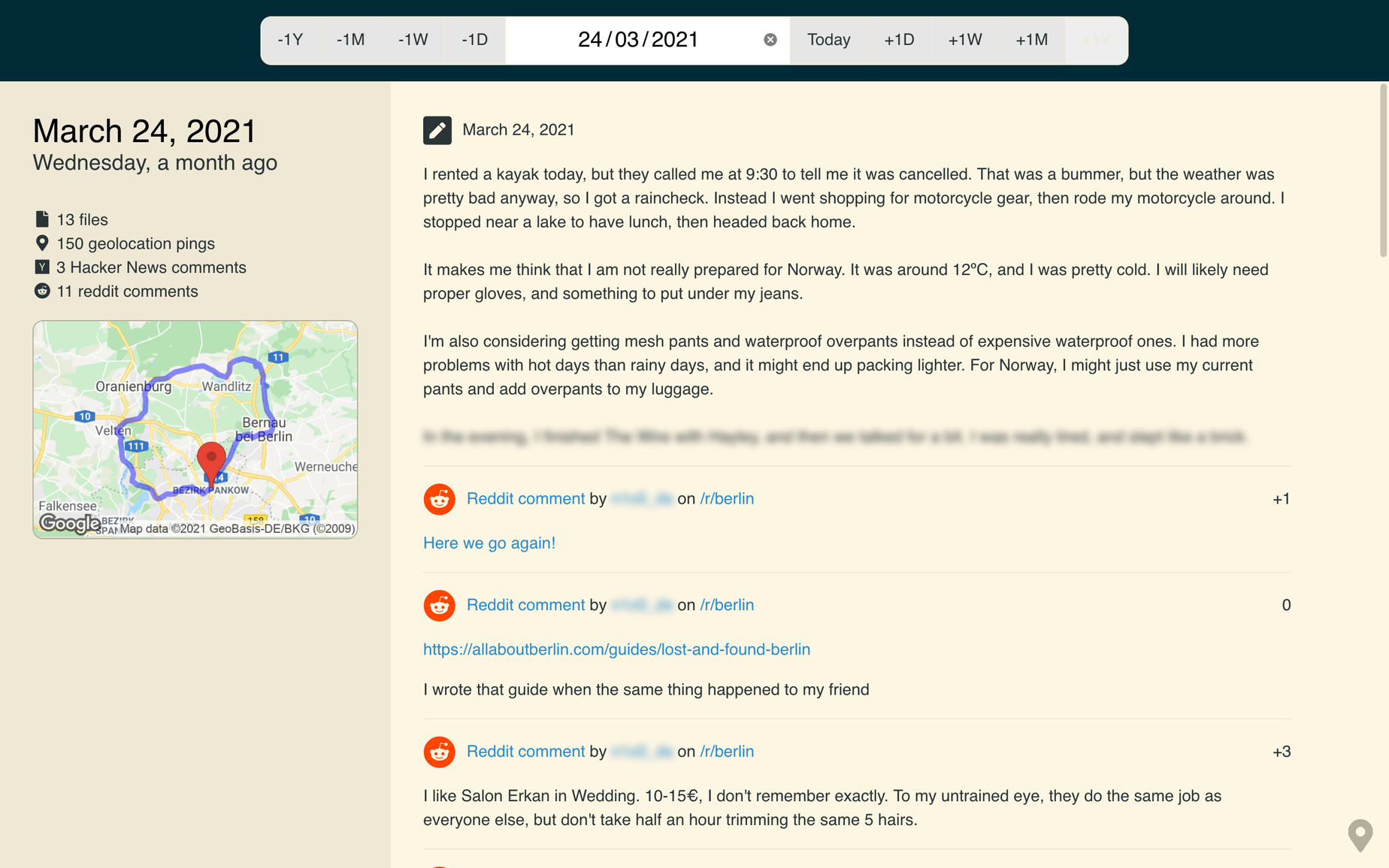

I built a tool that collects and preserves these crunchy bits. It doesn’t just collect photos, but also sketches, messages, social media posts, geolocation, calendar events, transactions and much more. It’s a rich, all-encompassing diary, a sort of second memory.

Okay, but what does it really do?

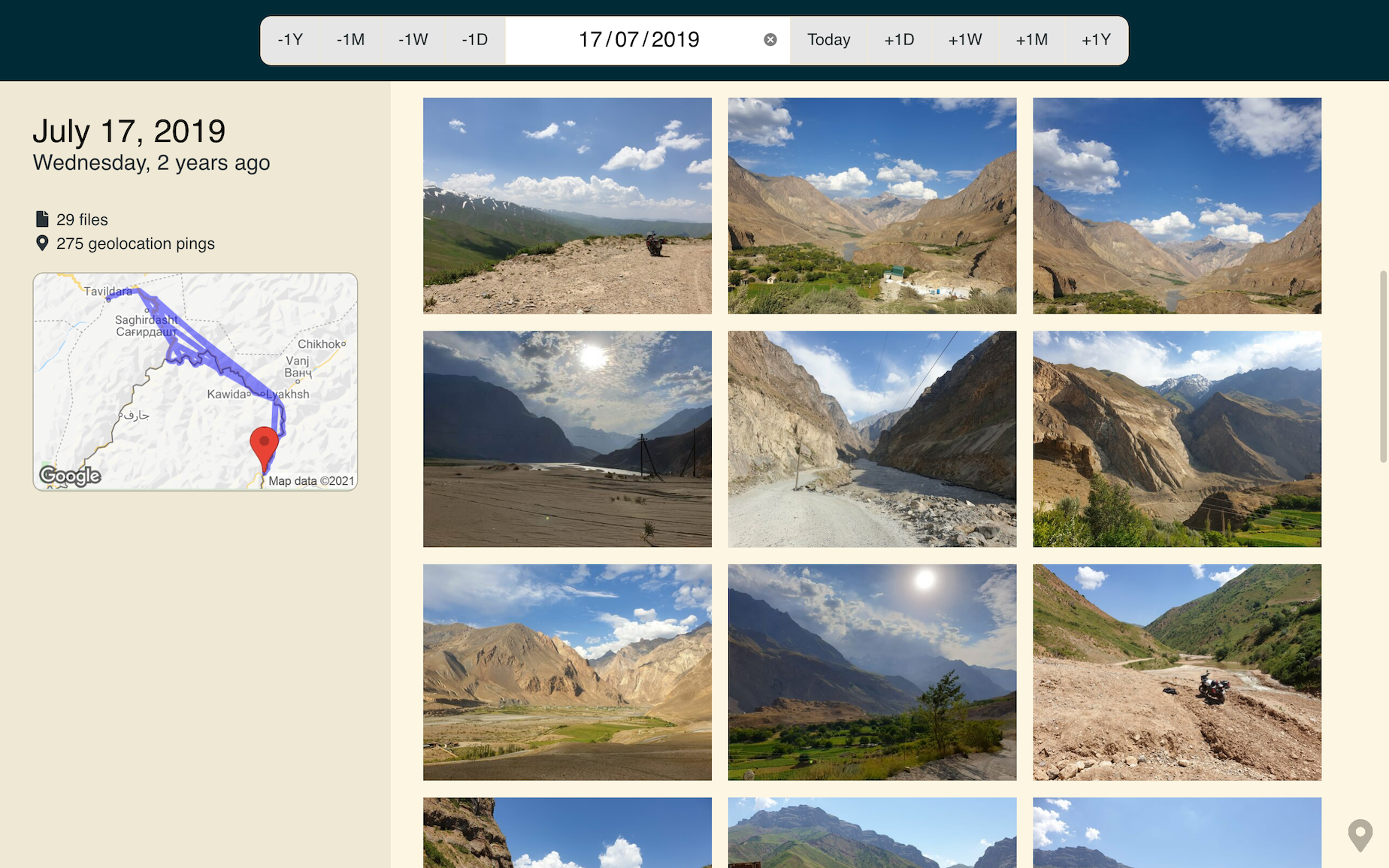

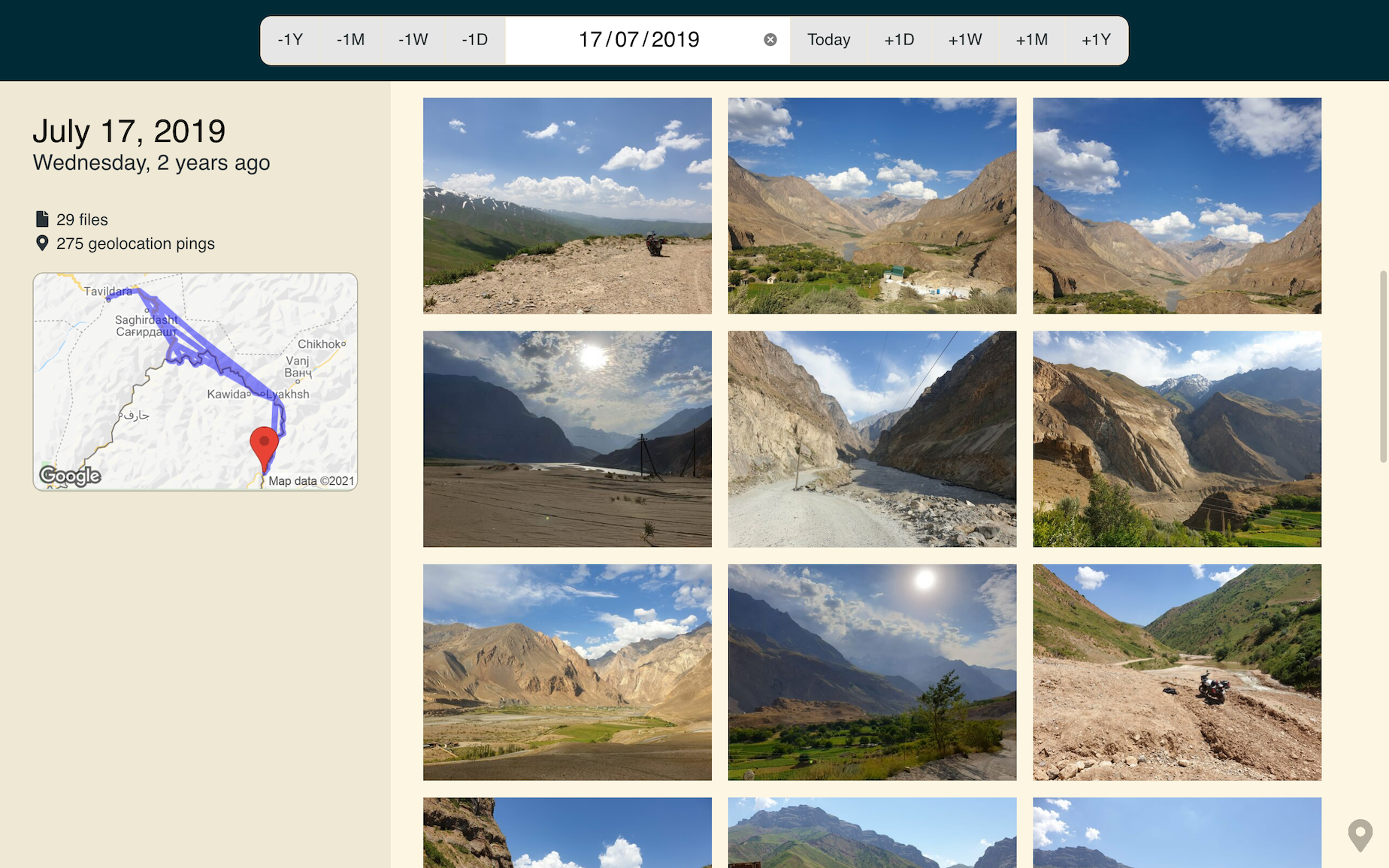

It collects all your crap, and it puts it on a timeline.

But… why?

I thought it would be neat.

“Why the hell would we want to [launch an anvil 100 feet in the air]? I get that a lot from women y’know. Women say why would you want to do that? and I don’t know other than it just need launchin’ sumpin’ that wadn’t intended to be launched.”

— World champion anvil shooter Gay Wilkinson

This project had been on my mind for a while. I wanted to bring my travel diaries, photos and location history together as a single timeline. It would be fun to pick a random date and see what I was up to, what (or who) I was into, and how I felt about it all.

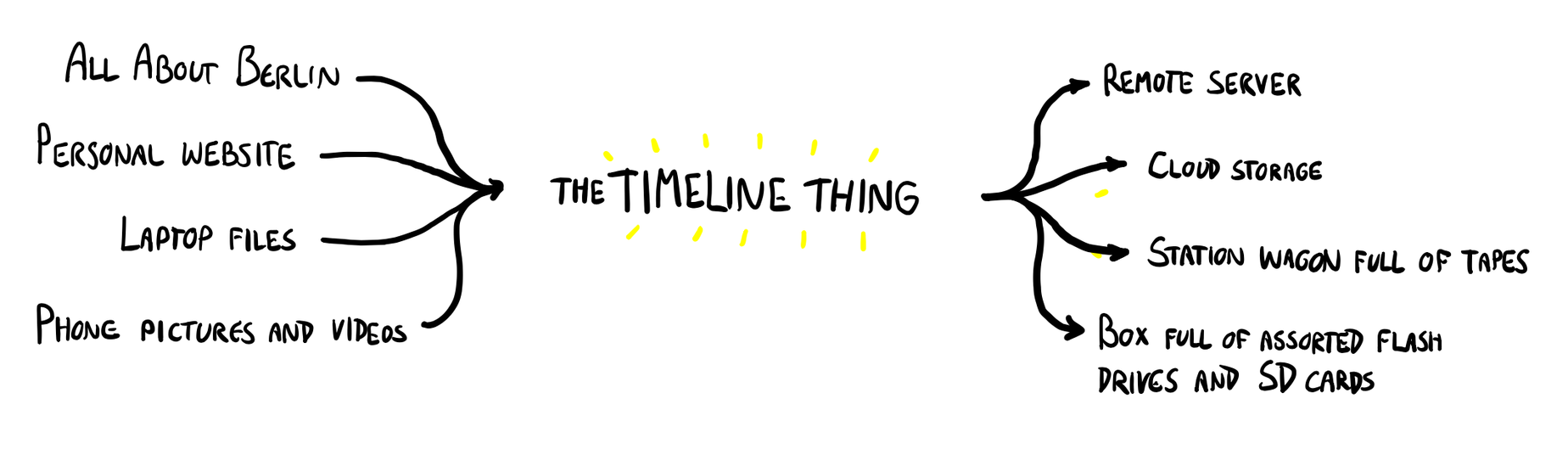

In an entirely separate problem domain, I needed a better way to organise my computer, phone and server backups. I wanted to collect all the data in one place, then make copies elsewhere. Since the timeline feeds off the same data, I thought I could kill two birds with one stone.

How does it work?

This is better explained in the project’s README.

In a nutshell, the server processes data from Sources (for regular imports) and Archives (for one-off imports), and turns them into Entries (things on the timeline). It pulls data from my laptop, my phone, social media, RSS feeds, GDPR data exports, bank transaction logs etc. In some cases, the data is pushed from another system, like the geolocation recorder I wrote for it, and the journal editor built into web interface.

After all that data is converted into timeline Entries, it shows up on the web interface. The web interface gets the Entries from the API as JSON, and displays them as it sees fit. Some Entries show as thumbnails, other as posts or as points on a map.

The tech stack is fairly conservative. It’s a VueJS frontend, and a Django backend. It runs inside Docker on Ubuntu on a 10 years old ThinkPad in a home-made rack under my desk on a mini PC in my living room. It’s the same machine that runs Nickflix.

Where does the data come from?

The most unsettling aspect of this project is the provenance of the data. Most of the hundreds of thousands of entries come from data Google and Facebook already had about me. Half a million of them come from GDPR exports, and those are not even complete.

Facebook and Telegram had hundreds of thousands of messages. Google had 8 years of geolocation history - over 50,000 data points in total - and years of emails, search queries, browsing history etc. They also had audio recordings of every time I used “Ok Google”. That’s on top of the content I willingly share on social media: tweets, status updates, comments, etc. I yet have to tap into the thousands of emails that passed through Gmail.

As I was exporting that data, I ended up closing many accounts, and scrubbing a lot of personal data from the internet.

Fortunately, there was also data I already controlled: geolocation data from my photos, GPX tracks, posts from my blog, SMS message dumps, git commits, etc. That data is a lot easier to import, because it’s not locked behind clunky APIs and data export tools. If I need a better way to import data, I can just create it. For example I can add RSS feeds to my websites, and let the timeline consume them.

My data, my rules

Once the data is stored on the timeline, I can do anything with it. This paves the road for all sorts of interesting features.

For example, the API returns entries as JSON, but I extended it to also return GPX files. This lets me convert my location history into GPS tracks. I uploaded one such trace to Open Street Map, and used it to map a new trail.

During my motorcycle trip in the Balkans, I whipped together a map that shows my recent location history. I made it so that my family can log in and see where I am. If something goes wrong, they know where to send help. I removed that feature when I returned home, but I plan to rebuild it properly for future trips.

Challenges

Getting the data

Accessing the data is often the biggest challenge. I want to make the data imports automatic and repeatable, and only rely on manual imports when I have no other choice. That usually isn’t possible. When a service becomes large enough, it restricts access to its APIs, and holds your data hostage. You can only access it through their app, on their terms.

Take Google Photos for example. Since June 2019, it doesn’t sync with Google Drive. You can only see your own photos through their app. Getting them onto a computer you own became really difficult. Google Takeout still lets you export all your photos, but it’s a rather clunky, manual process. Twitter makes it hard to get API credentials nowadays, so the API is out of reach for most. Fortunately, I had old ones I could reuse. Reddit’s API only returns the last 1000 comments, so it’s missing about a decade worth of comments. Many websites just don’t offer any API at all.

If it wasn’t for GDPR forcing websites to give you access to your own data, this project could never get off the ground.

Ironically, the EU’s open banking initiative, which forces banks to open your data to third-party services (like accounting software), does not actually let you to access your own banking data. There is no room in this grand scheme for people who just want their own transactions in JSON format. Intermediary services don’t offer a pricing tier for individuals. Fortunately, my bank still lets me export my transactions in CSV format, or my entire data in JSON format. However, there’s no way to automate the process. I have to manually export my transactions every month, and import them as an Archive. So be it.

For small, one-off data imports, I convert the data to JSON with throwaway scripts, and import that. There’s an Archive type for that. I imported all the SMS messages I sent or received from 2013 to 2015 this way, and hundreds of diary entries I once kept in text files and Google Keep notes. Now they all sit neatly on the same timeline.

Generating previews

I had to generate preview for thousands of photos, videos and audio clips. I used ImageMagick and ffmpeg to do it.

Video previews were an interesting challenge. I wanted to create the same kind of hover preview as you get on YouTube. When you put the mouse over a thumbnail, it shows 1-2 second bits of the video. I’ve achieved this with ffmpeg maps. I just used a bit of Python to calculate which parts of the video to use, as shown here.

Time zones

Time zones are hard. I store Unix timestamps and print UTC dates to remove some headaches, but with some of the data, it’s not that simple.

For example, EXIF metadata does not have time zone information. It just uses the camera’s date. I could assume that the camera uses whichever time zone I live in, but it’s clunky and rather inaccurate.

That’s also an issue when displaying the data on the timeline. If I’m in Germany, everything I did in Canada is off by 6 hours, and everything I did in Kazakhstan is off by 5 hours in the other direction. I could use the surrounding geolocation entries to infer the time zone of each entry, but that’s getting a tad complex. I decided to just close my eyes and pretend the problem isn’t there.

Dates

It wasn’t any easier to figure out when things happened, and where they should appear on the timeline.

A photo could appear in multiple places: on the date it was taken (if it’s known), on the date the file was created (if it’s known), and on every date the file was modified. All of those dates are inaccurate, if they’re available at all.

Currently, I look at 3 things, in order of priority:

- The date written in the file name. For example,

selfie - 2020-03-22.jpg. This is useful for notebook scans and other documents, since the file’s creation date is not the physical document’s creation date. - The EXIF date. This is a semi-reliable indicator of when a photo was taken. It has no time zone information, and can be way off if the camera’s clock isn’t set properly, but it works really well for smartphone pictures.

- The file modification date. I can’t use the file creation date, because it’s not available on many filesystems.

Data formats

Parsing hundreds of thousands of files from dozens of different devices led to all sorts of interesting problems.

I had to remember to include .jpeg and .mpeg files, not just .jpg and .mpg. I also had to include many other file extensions I completely forgot about: .m4v, .mod, .mts, .hevc, .3gp, .raf, .orf and so on. Thankfully, ImageMagick and ffmpeg could make thumbnails out of those without breaking a sweat.

EXIF data gave me so much trouble that it’s worth its own post.

Large files

Archives can be very large, and sometimes multipart. When playing with large files, you always encounter weird new issues.

I had to configure multiple application layers to allow large file uploads, and long request/response times, so that I could upload 5+ GB Google Takeout archives. I also had to clear space on my laptop just to test Google Photos backup imports. Even then, I still run into issues when uploading larger archives. The solution might be to implement multipart uploads, but that sounds like a pain in the lower back.

Importing large amounts of date through the browser is also troublesome. If you paste 5 MB of JSON in a text field, your browser will freeze, then crash.

When processing large files, you have to buffer the data. If you load it all in memory, you might quickly run out of memory. You also have to be frugal with CPU usage, because it runs on old hardware alongside other projects. I pulled many interesting tricks to speed up the backups. It’s pretty fun to tackle those little challenges along the way.

Zip files

Zip files can encode their file names in two ways: CP437, or unicode.

Each operating system does it wrong, but in a different way1. For instance, Mac OS encodes its zip files as unicode, but doesn’t set bit 11 correctly, so Python (correctly) reads them as CP437, and garbles the non-ASCII characters in file names.

I wrote a quick and dirty workaround for Mac OS archives: if the file doesn’t exist, encode the name as CP437 and check again. I’ll think of something more clever if I ever switch to another OS.

Noise

My home server sits in my open living room. I don’t want to hear the fans spin needlessly when I’m reading on the couch. This led to performance tweaks I would have otherwise overlooked, like this one. This CPU-intensive task used to take 3 minutes, and now it takes 20 seconds. It finishes before the fans spin up.